The Numbers That Explain the Success of a TV Show About School

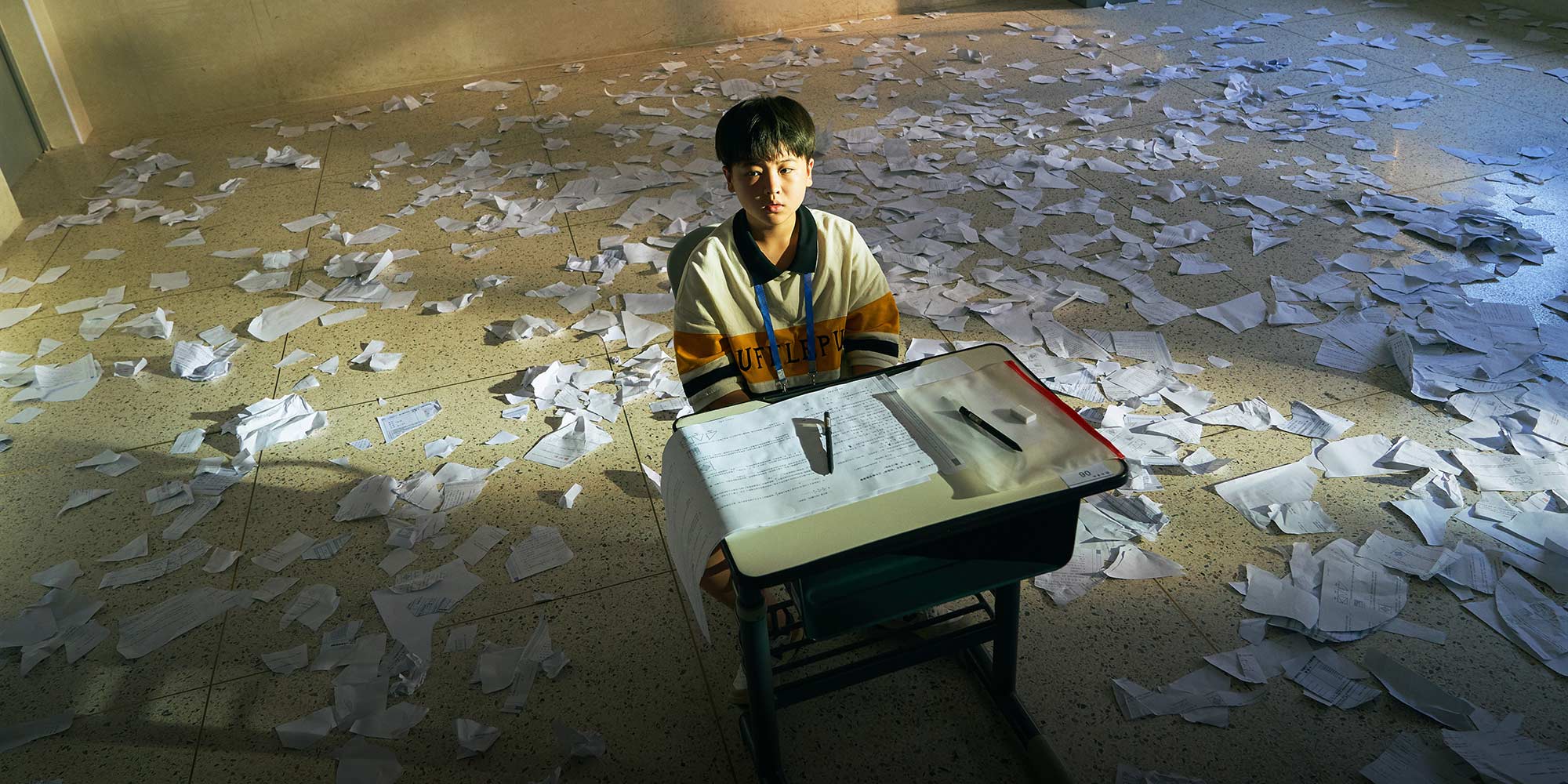

In an emotional scene from the Chinese TV show “A Love for Dilemma,” which chronicles primary schoolers’ transition to middle school, a sixth grader tearfully reflects on how his mother pushes him to get good grades.

“My mom doesn’t love me,” he says. “She only loves me when I score full marks in an exam.”

The show has hit a nerve among viewers. On microblogging platform Weibo, posts about the show have been viewed more than 3.5 billion times. The show’s hotly anticipated finale will air Monday.

One reason why “A Love for Dilemma” has inspired so much discussion is because its tense storylines reflect the experiences of many families in China — where competition to secure admission to a top school is relentless.

The Chinese government has long sought to curb the excesses of China’s educational rat race. On April 25, the Ministry of Education published new guidelines for student homework, saying first and second graders should have no written assignments, and that older primary schoolers and middle schoolers should spend on average no more than an hour or 90 minutes per day on homework, respectively.

Yet research shows many schools give their students far more work than that. According to the annual report on children’s development in 2019 co-published by the China National Children’s Center and Social Sciences Academic Press, students on average needed nearly 1.5 hours per weekday to finish their homework, and 2 hours per day on weekends.

And it’s not just homework that keeps Chinese students busy after school. About half of all children are enrolled in tutoring classes to improve their grades. Most primary schoolers also take sports, music, or other interest classes — though attendance is lower among middle schoolers.

With homework and tutoring taking up so much of children’s schedules, there’s often not enough time left to sleep. In early April, the Ministry of Education released another notice that limited the opening hours of after-school training centers in an effort to give children enough time to rest. Figures show that, over the past decade, Chinese children have been getting less and less sleep.

Editors: Liu Chang and Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: A still frame from “A Love for Dilemma.” From @电视剧小舍得 on Weibo)