In Rural China, a Marriage, a Tearful Bride, and a Debate Over Consent

HENAN, Central China — A week after the wedding that made Zhuwa Village the center of a nationwide uproar, residents are still perplexed about why it attracted so much attention at all.

In early March, a short video had shocked the country. It showed a 20-year-old woman with a severe intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) marrying a man 35 years her senior. The bride is seen sitting on a bed, sobbing loudly as the groom wipes away her tears with tissues. The camera pans then to the bride’s mother, who is seen grinning widely, as an unidentified man says in the background, “Don’t cry. You’re about to get married. Don’t cry.”

The video raised questions about consent — the bride, surnamed Yao, is barely able to walk or communicate — and about the vagaries of China’s legal system when it comes to marriage and mental disabilities.

In response, local officials clarified that the wedding ceremony — which carries no legal significance — was not against the law. But, because Yao’s IDD rendered her unable to provide consent, they could not apply for a marriage license that would make them husband and wife in the eyes of the government. Current laws, however, allow them to live together and, should they later have children, the couple can apply for birth permits and the mandatory household registration, or hukou.

In Zhuwa, however, few share the concerns raised online, and locals have grown wary of outsiders. “Nobody here has an intellectual disability,” a middle-aged woman, one among a few villagers chatting by the road, blurts out when approached. Another woman quickly adds, “It’s normal for a young girl to get married. What’s there to ask about?”

Meanwhile, wedding attendees say Yao cried because she had pain in her leg, and was scared of strangers. And to Zhuwa villagers, the couple’s pairing doesn’t seem worthy of any outrage. “What a trivial thing,” they say, adding, “What’s wrong with finding a husband for a girl like her?” To them, marriage is the only way for women like Yao to find the long-term support they need. Parents will grow old, and the government provides little social welfare in places like Zhuwa.

By government standards, Yao’s family is considered poor. A 2017 list of the area’s impoverished households included the families of both her father and her uncle, the cause of their poverty described as “unskilled” and “lacking labor,” respectively. The bride’s father lives in a two-story brick house belonging to his brother, reportedly having moved in after his own home had collapsed. His front gate shut, he wasn’t available for comment.

Locals described Yao’s father as “honest,” and two elderly women say he loved his daughter dearly and had raised her for 20 years, taking care of all her needs. Having developed IDD early in her life, Yao was homebound most of the time but occasionally ventured outside at night with her father. Those in the village say her gait was abnormal and she fluttered her hands while walking.

Many say Yao’s marriage was entirely orchestrated by her father, who had been in talks with the groom for over a year. Yao’s father told reporters that he wanted to find someone to take care of his daughter. “If I don’t marry her off, then who will look after her in the future?” he said.

One villager agrees, saying about Yao’s father: “He’s 68. Think about it: He won’t be able to provide for her or help her for much longer.”

The Voiceless

Over a decade ago, Pan Lu, a scholar at China Agricultural University, found that those in rural areas generally held positive attitudes about women with an IDD getting married. In most cases, parents arranged such marriages so their daughters would have a caregiver in the future — just as Yao’s father had done.

Researching the lives of people with IDD in two villages in the northern Hebei province for her doctoral dissertation, Pan found that women with IDD still yearned for the emotional intimacy found in marriage and family life. For example, one young woman with a mild IDD would put on heels she had for special occasions and take her husband’s arm as soon as he returned from work.

Getting married, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that the rights and interests of women with disabilities have been realized or protected. Pan, who lived in the two villages for six months, believes such women have no decision-making powers when it comes to their own marriages, and their own consent and opinions are completely disregarded.

It’s not much different in Yao’s village.

Here, locals believe Yao inherited her IDD from her biological mother, who left the village some years after her daughter was born. Yao’s father later remarried, but villagers call both his wives xinzi — which in the local dialect refers to someone with an intellectual disability who is unable to work.

Touching upon the controversy following the video, some locals say: “The way reporters talk about it, you’d think that it’s illegal for a xinzi to get married.” Asked whether Yao wanted to get married, an older woman retorts, “What the heck does she know? She doesn’t know about eating or drinking unless you give her something to eat and drink. That’s just how a xinzi lives.”

In the course of her research, Pan found that such marriages were devoid of emotional intimacy, and wives with IDD received inadequate support from their husbands.

For example, the same woman who put on heels to greet her husband still lived with her parents after getting married. Another couple who had lived together for more than 20 years rarely met outside of eating meals, spending their days on their own and sleeping in separate rooms. According to Pan, the husband of the second woman admitted that he didn’t care about what she did during the day and said, “Seeing her annoys me.”

“The lack of awareness for people with IDD makes it hard to improve their lives,” Pan says. “Especially given the prevalence of stigmas and social rejection.”

A driver from Biyang County, where Yao’s village is located, recalls escorting poverty alleviation officials to one family on multiple occasions. There, they found the husband’s care for his wife, who had an IDD, extended only as far as giving her food. Later, when he moved into government housing, he refused to let her move in, because he didn’t want her making a mess.

An Urban-Rural Divide

In urban areas, the treatment of people with IDD — particularly women — is a different story.

A 2006 study of 216 people with IDD in Nanjing, the capital of the eastern Jiangsu province, determined that the group’s marriage rate was only 12.68%. Of those surveyed, 96.8% of the men and 80% of the women were unmarried.

And in 2008, Chen Lianjun, a graduate student at East China Normal University, interviewed parents of 29 urban residents with IDD. Only six supported them getting married, and 26 saw marriage as an additional burden on the family.

Last year, a Chinese TV show “The Mediator” aired an episode in which a man wanted to marry his girlfriend who had a moderate IDD. Her septuagenarian mother, however, opposed it because she thought him unreliable.

She only wished her daughter to live peacefully to the age of 50, when she’d reach the legal retirement age for women. To that end, the mother contributed toward her daughter’s social insurance using the daughter’s relatively generous urban monthly allowance of more than 1,000 yuan ($150), which included a subsidy for people with disabilities. Once her daughter retired, she would be able to collect and live on 3,000 yuan a month. If that didn’t work out, the mother figured their community nursing home would be able to look after her daughter.

When it comes to benefits, the contrast between urban and rural areas is stark: Compared with the woman featured in the TV show, Yao only receives two monthly 120 yuan subsidies for disabilities, along with 335 yuan in subsistence allowance.

For the mother on “The Mediator,” her main concern was the unfair treatment her daughter might suffer after marriage — an all-too-common reality.

Compared with people without disabilities, scholar Pan found, women with IDD are more likely to experience abuse at home and in their marriages. Their lack of sexual awareness and reduced self-defense capabilities leave them vulnerable to sexual assault.

A study of 90 legal documents on the platform China Judgments Online about divorces involving people with IDD showed that the vast majority were filed by the spouse with an IDD after “being hit” or feeling a “lack of care.” In many cases, the husband deserted the family once a child was born.

Also, in most of the 90 cases, the wife had an IDD. Based on her study of the Hebei villages, Pan wrote in her dissertation, “The biological functions of these women with IDD are completely stripped away from their attributes as full social beings, making their fertility the main factor leading to and sustaining marriage.”

In the Hebei villages, Pan observed the women’s naivete, passions, and desire to connect with people. But in reality, their lives were dictated and overseen by people without disabilities, leaving them with no way to speak up or improve their circumstances on their own.

Over a decade has passed since Pan completed her dissertation, and though she never pursued that research topic further, she always paid closer attention to news about the issue. She believes the past few years have brought few changes to the lives of rural women with IDD: The problems they face remain unresolved, and there is a lack of understanding about them.

Pan also found that women with disabilities in rural areas had their marriages arranged by their families, usually to disadvantaged men in the village who were older, had physical disabilities, or struggled financially. One woman she knew was wed to an older man with a vision impairment; another was 20 years younger than the man she married.

“An Honest Man”

At 55, Zhang from Biyang County’s Hegang Village is 35 years older than Yao.

And just like his father-in-law was described in Zhuwa about 6 kilometers away, most locals here also have the same thing to say about Zhang: He is “honest but poor.”

Most brick houses in Hegang Village were built in the 1990s, but Zhang and his father managed to build their one-story, two-bedroom home only about 10 years ago. Zhang lives in the bedroom to the left; his octogenarian father, who is paralyzed, occupies the room on the right and relies on Zhang for care. Unlike their neighbors, they never installed a steel gate in their courtyard.

His cousin says that if Zhang had a choice, he wouldn’t have chosen to marry a woman with an IDD, except that “he’s too poor.”

According to the cousin, Zhang never finished elementary school but worked the land and cared for his father instead. He was also hired out as a bricklayer in the nearby areas. Farming brought in meager income, and the village’s water problems — alternating between floods and droughts — put them at the mercy of the elements. Any wheat, rapeseed, and peanuts they managed to grow sold for very little, just enough to cover their basic necessities.

The cousin’s daughter is also quick to support Zhang. Recalling him fondly, she says that whenever she’d visit him, Zhang always smiled and played with her despite not being very talkative.

The rumors online that Zhang had purchased a bride make her blood boil. She says that he actually planned to give Yao’s family a betrothal gift of 10,000 to 20,000 yuan, but her father refused.

Zhang has three brothers and three sisters, all of whom are married. Villagers say his two older brothers had married via “exchange marriages” — they wed two sisters, and in exchange, their own sisters married two brothers from that same family. But Zhang kept putting off his own wedding, which his cousin attributes to his introverted, reticent personality; he remained single into his 50s.

The cousin counted three bachelors in their community older than Zhang. All three are orphans in their 60s and rely on government welfare for food, clothing, housing, health care, and burial expenses.

Locals in the bride and the groom’s villages are all too familiar with the challenges of finding a wife these days. The cost of getting married itself is also a factor, considering housing is priced at 4,000 to 5,000 yuan per square meter in Biyang County, and a car is thousands of yuan. Not long ago, a young man paid the “moderate” sum of 99,000 yuan as a betrothal gift.

“Especially in villages, young people tend to go out to work for a living. Young women — whether single or married — move to the cities,” says the cousin’s son. “It’s better living there and they can see the world, but that makes it harder for the men.”

The cousin’s son lives in the county seat of Biyang but returned to the village after the uproar over the video. He went on several interviews underscoring two points in particular: that the bride wasn’t underaged and that nobody was engaged in trafficking.

He says, “If you think people with IDD have the right to get married, then isn’t it worth it for everyone to help make it happen?”

However, the legality of Zhang’s wedding to Yao is still unclear to him — and is his biggest concern.

Pointing to an apple tree in the courtyard, the cousin’s son says, “Take that tree, for instance. It’ll be harvested in August, whether it grows well or not. Though she (Yao) has an IDD, she is physically an adult and, as such, should be treated equally, not discriminated against.”

But lawyers differ on this point. When China’s first unified civil code went into effect in January, it removed a clause from an earlier marriage law that had included people with severe IDD among those “medically unsuitable for marriage.” The move was heralded as a major improvement toward guaranteeing the marriage rights of people with disabilities.

But in order to register for marriage, couples will have to show some form of consent. For people with severe IDD like Yao, expressing their true intentions can be difficult. At the same time, the Ministry of Civil Affairs lacks the authority to determine if an individual has a severe IDD.

And when it comes to consent, many lawyers believe that sexual relations with such individuals would constitute rape, but others have pointed out that provisions in China’s new civil code regarding guardians’ duties also merit consideration. “As long as (marriage) is in the interest of the person concerned, then the guardian can decide on behalf of that person,” one lawyer told The Beijing News.

Nobody may really ever know what Yao herself thinks about marrying or having children. As the uproar over the video slowly fades, Hegang Village, where Yao and Zhang now live, has returned to its usual quiet.

The peach trees bloomed early this year, splashing a layer of pink amid the green wheat fields and golden rapeseed flowers. But a swift temperature drop only a few days ago turned the villagers’ focus onto more important matters: whether or not the peach trees will even bear fruit this year.

Lü Hui also contributed to this article.

This article was originally published by White Night Workshop. It has been translated and edited for length and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Lu Hua and Ye Ruolin.

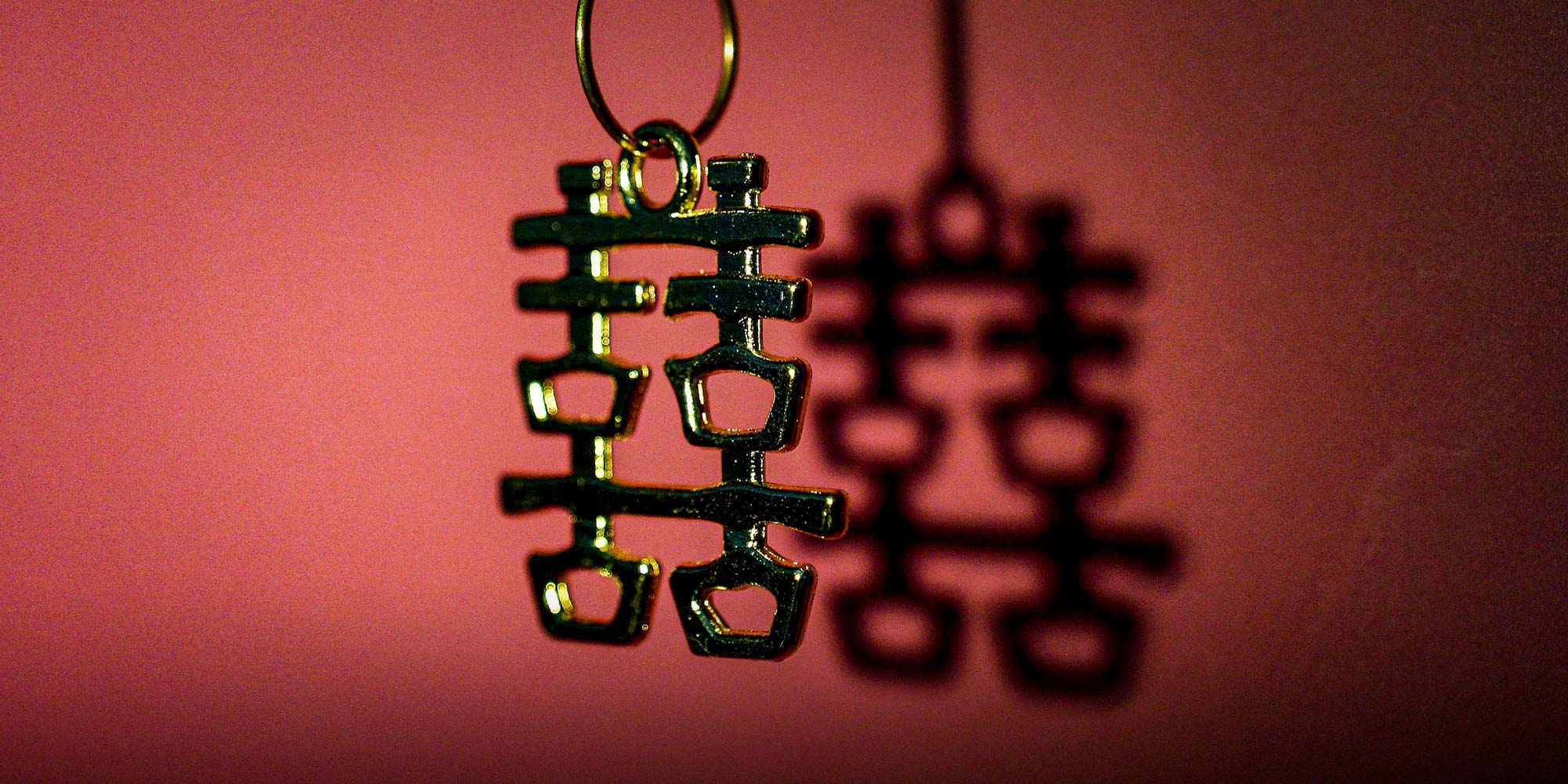

(Header image: 500px Moment/People Visual)