Confronting China’s Child Sex Abuse Crisis: The Story of Sisi

This story is part of Sixth Tone’s five-year anniversary project Changemakers.

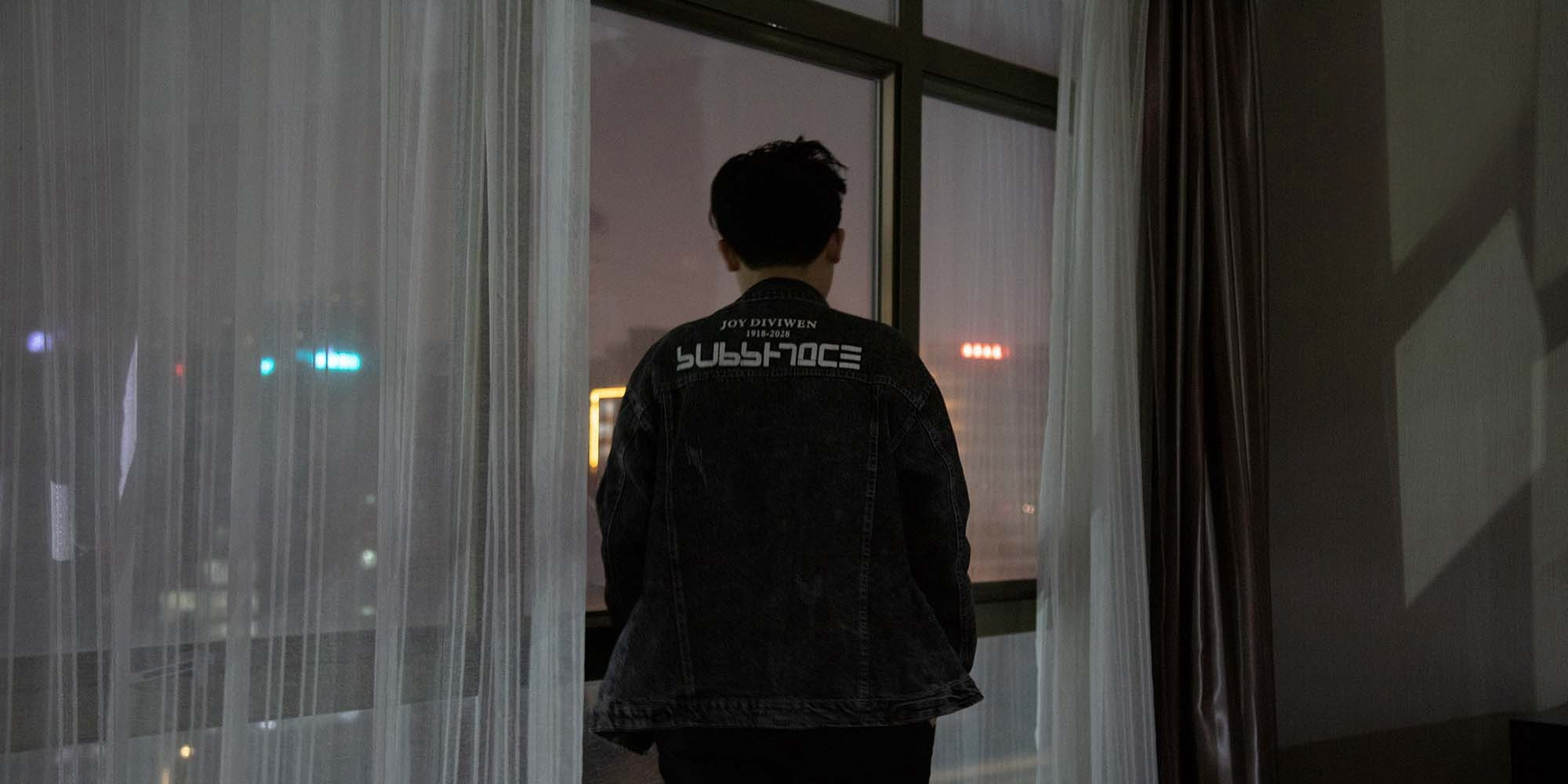

Sisi doesn’t wear women’s clothes anymore. It’s too dangerous.

The 20-year-old meets Sixth Tone outside the factory where she works in Dongguan, the southern Chinese export hub. Emerging from a crowd of workers clocking off the day shift at 8 p.m., she looks completely different from the girl we interviewed five years ago.

Her hair is cropped short, her figure concealed by a baggy shirt and jeans. On her feet are a pair of men’s leather loafers. The outfit helps her avoid unwanted attention from men, she says.

“I feel much safer this way,” Sisi tells Sixth Tone.

The comment is a sobering reminder of the trauma the young woman has experienced.

Sisi, a pseudonym, is arguably the biggest reason China was forced to confront the prevalence of sexual abuse against minors. A survivor of multiple rapes, her case focused public attention on an issue that had previously been a taboo subject in Chinese society.

Yet her story also shows how much more needs to be done to protect China’s girls and young women. While the government has increased efforts to deter sex crimes in recent years, survivors still face stigma and struggle to find justice. And this lack of support inflicts further emotional scars.

Sisi first came into the public spotlight in 2012. Then just 11 years old, she had become pregnant following repeated sexual assaults. The perpetrator — a 74-year-old man who lived in the same village as Sisi’s family in central China’s Hunan province — was sentenced to 12 years in prison in April 2013, a month before Sisi gave birth to her first child.

The case was one of several child sex abuse scandals to receive wide coverage in Chinese national media that year. In May 2013, the same month Sisi gave birth, eight cases involving schoolteachers sexually assaulting students were reported by the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China.

The reports sparked public outrage, bringing the issue unprecedented attention. A few weeks later, over 100 female journalists jointly launched Girls’ Protection, a nongovernmental organization that has become a leading voice demanding crackdowns on child sex abuse.

But Sisi’s ordeal was far from over. After she gave birth, her family sent her to the southern metropolis of Shenzhen under the care of a man surnamed Xia, who ran several kindergartens in the city. There, the child became pregnant again.

Sisi accuses Xia of raping her. In 2015, the then-14-year-old gave birth to her second child.

This second incident created an even greater furor, with journalists flocking to Sisi’s home village in Hunan. Xia, however, has never been charged, and the case remains unresolved. The inaction by the Shenzhen police still baffles Lai Weinan, a lawyer who represented Sisi in the case.

“We reported the incident in 2015 and pointed out that a DNA test would easily prove the man to be the perpetrator,” says Lai. “The police’s only reply was that they understood the situation and would follow up. But they didn’t do anything, and eventually they dismissed the case, citing a lack of evidence.”

When contacted by Sixth Tone, Shenzhen’s police bureau confirmed the case had been closed due to lack of evidence, adding that the officer who led the investigation had left the department. Sisi has the option of asking the authorities to reopen the case, but she has decided against doing so, saying she wants to move on with her life.

The way the case was handled has done Sisi lasting harm, Lai says: She was denied justice and did not receive the support she needed.

“It can change the life path of a victim,” Lai says. “With Sisi, we can see she later lost trust in people.”

In the years since, China’s justice system has begun to take cases like Sisi’s much more seriously, as child sex abuse has become a hot-button social issue. Since 2013, when Chinese media reported 125 cases, coverage has increased to more than 300 per year.

In 2016, the government introduced landmark legislation to strengthen protection for vulnerable children — especially those “left behind” in rural areas by parents working in cities. New measures to further increase safeguards against sexual abuse in the education system were implemented two years later.

Then, last year, Chinese authorities went a step further by enacting a “mandatory child abuse reporting mechanism.” The policy requires people in close contact with minors — including teachers, health professionals, hotel staff, and charity workers — to report any suspected abuse immediately, and states that police should open an investigation without delay.

According to Zheng Ziyin, deputy director of the All China Lawyers Association’s minor protection committee, the new rules have already made a real difference, as schools no longer have any incentive to cover up abuse. Last year, authorities in Hunan province brought criminal charges against two school principals for failing to report instances of sexual abuse.

“Schools used to be concerned they’d be liable for anything that happened on campus, as safety is taken into account for school evaluations,” says Zheng. “But now, the new regulations are literally telling you: If you don’t report child abuse cases, you’ll be in trouble.”

Yet statistics suggest a huge amount of abuse continues to go unreported. Between 2017 and mid-2019, Chinese courts handled 8,332 child molestation cases, only a slight rise from the 7,610 cases processed between 2013 and 2015.

For Sisi, the new rules are far from enough to protect girls from abuse. “Do you believe all the bad guys have disappeared? Do you think the new laws will simply scare them away?” she asks. “I don’t think so.”

Indeed, little appears to have been done to change social attitudes toward child abuse. Girls still often get blamed for the abuse perpetrated against them, leaving survivors with deep emotional scars.

“Older parents and those from rural areas find it more difficult to process the tragedies,” says Zheng. “When that happens, it becomes extremely difficult for the victims to properly heal.”

In Sisi’s case, her family’s lack of understanding has been a continual source of pain and frustration during the past five years.

Ever since she was a girl, Sisi has largely had to look after her own well-being. Her parents, who had an unhappy marriage, would often beat her. After she was raped, they quickly concluded the attacks signaled their daughter was a “bad girl.”

When Sisi left Hunan to move into a women’s shelter in Beijing after the birth of her second child, her father told her: “You have brought shame on our family.”

As she has grown older, Sisi has shown a reluctance to rely on others. When Sixth Tone first met her in 2016, she was living with her secondborn — then 10 months old — in a home provided by the charity Children’s Hope Foundation in Beijing. Social workers at the charity were arranging vocational training for her, and promised to help her find a job.

But Sisi never finished the program. In June 2018, she decided to leave the shelter, as she worried she’d become too dependent on her tutors.

“Sometimes, I regret it — I was too young and impulsive,” says Sisi. “But the past is the past. Now, I’m a grown-up. I have to count on myself. I have to make money. I have children to support.”

After returning home to Hunan, Sisi’s relations with her parents deteriorated further. Her father, Li Chunsheng, still appeared to mistrust her, Sisi says.

“When I was working as a delivery driver on the Meituan app, he even asked me: ‘Are you really delivering food, or other services?’” she recalls.

At the same time, Li appeared determined to arrange a marriage for his daughter. While Sisi spent a month in the hospital with a persistent low fever — a side effect of the sexual assaults, which have left her with severe vaginal inflammation — Li set her up on dates with several local men.

“There are many single men looking for a wife here,” Li tells Sixth Tone. “Though all my neighbors know about Sisi’s encounters, matchmakers would still come to my door. … One family even offered me 100,000 yuan (then $15,000) for Sisi to marry their son.”

Outraged by her father’s actions, Sisi rebelled: She decided to stay with the very first date she met. She has since had a third child with the man, and refers to him as her husband, even though the couple have yet to legally marry. (Sisi only recently reached China’s legal age for marriage, which is 20 for women.)

“He’s 18 years older than me, but he’s been nice to me and so have his parents,” Sisi says. “When I saw how his parents took care of my son, I felt that was the love I’d been lacking.”

Sisi says she’s happy with her partner, but confesses she’s still afraid of most men. At work, she tends to make friends only with female colleagues.

“We can understand each other better and communicate more smoothly,” she says.

Though it’s impossible to know how Sisi’s life might have been different had her family been more supportive, experts say providing more psychological education to parents of child abuse survivors can help children recover from their trauma.

“Psychological education programs can be delivered at much less cost than individual therapies (for survivors). … It can easily reach a certain scale,” says Pekka Santtila, a professor of psychology at New York University Shanghai. “If a child is victimized, the police and social workers can make sure their parents access the right resources for tips on how to speak about it, how to deal with it, and what type of questions are useful.”

China’s newly revised law on the protection of minors, which comes into effect in June, includes measures designed to expand access to such education. As well as making sex education mandatory in schools, the law states that parents of child abuse survivors will be instructed on how to communicate with their children.

For her part, Sisi prefers not to dwell on the past. At just 20 years old, she finds herself a mother of three, and her main concern is ensuring her children grow up in a safe and healthy environment.

“I never want any of them to experience what I’ve been through,” she says.

While she has fewer worries about her second daughter and youngest son, who are living with her partner’s family, Sisi says she’s concerned about her eldest daughter, Yanyan. The child has been under the care of Sisi’s parents for years, and is currently living in a boarding school.

“Yanyan is very introverted. Every time I see her, I see myself,” says Sisi. “Neither of us talks much. … We keep things to ourselves. That’s why I’m worried about my parents putting her in a boarding school.”

Li, Sisi’s father, insists the private school is much better than the public institution Sisi attended as a child. “I’m confident she (Yanyan) is safe there,” says Li. “It’s very strictly managed. … And we have taught her not to eat things or accept gifts strangers offer her.”

But the 4,500 yuan tuition fee per semester is expensive for the family. Li doesn’t have a full-time job and lives on a 500 yuan monthly payment through China’s welfare system. The family relies on donations from relatives to pay Yanyan’s school fees.

Sisi is determined to take greater control of her kids’ care. She plans to officially get married this year, and then transfer her children’s hukou, or household registration, to her soon-to-be husband’s family.

“Then, the three kids can all live together and attend regular public schools, which will ensure they come back home every evening,” says Sisi.

The young mother is also working to become financially independent. Since late February, she has been living alone in Dongguan, working as a quality control officer on a factory production line. She now works 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., six days a week, earning 4,000 yuan per month.

“To find a job outside our rural hometown is the best proof you’re responsible to your family,” says Sisi. “I want to stay at this job for a long time, so I have a stable income. I need to save up for myself and my children.”

Scrolling through videos of her children on her phone, Sisi smiles. Sometimes, she admits, she’s unsure what role she should play with them.

“At times, I feel like their mother — I criticize them for being dishonest or taking others’ belongings without permission,” she says. “But most of the time, I feel like I’m their big sister. I’m growing up with them together.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Sisi poses for a photo at the hotel where she is being interviewed in Dongguan, Guangdong province, March 4, 2021. Jiang Yanmei for Sixth Tone)