Born in 1920: The Martyr in the White Scarf

This article is the first in a series on the lives and legacies of three women born a century ago, and how they intersected with and reflected some of the major trends of the past 100 years of Chinese history.

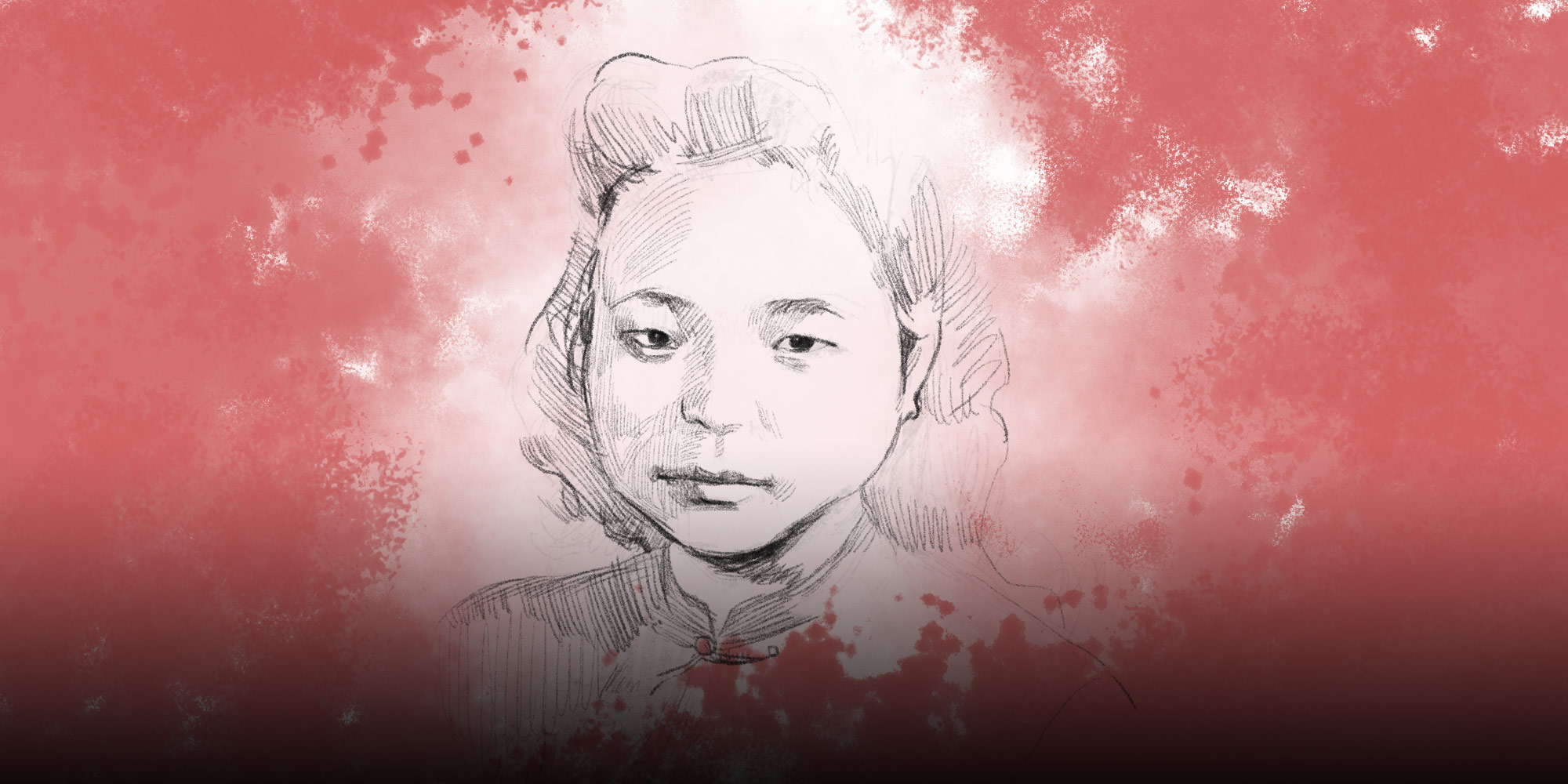

Mention the name “Sister Jiang” to someone in China, and it’ll likely conjure up a very specific image: a pretty woman with hair down to her shoulders, dressed in a red jacket over a blue qipao and wrapped in a long white scarf. Her features possess a certain stoic beauty, but in her eyes burns the fire of a revolutionary martyr.

Of all the women who died in service of the Chinese revolution, Sister Jiang is the one whose image has taken the strongest hold in the public’s imagination. Her status is comparable to that of the Soviet Union’s Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya or France’s Joan of Arc. And like her fellow martyrs, Sister Jiang burned brilliantly and died violently.

Jiang Zhujun was born on Aug. 20, 1920 into a poor peasant family in the southwestern Sichuan province. She had a difficult childhood and started working at a factory when she was just 8 years old. When she joined the Communist Party of China at 19, she was just a year older than the fledgling group itself. Although victory must have seemed distant, many progressive youths like Jiang saw the young party as their best chance to liberate the Chinese nation.

Jiang started working as a member of an underground CPC cell near the anti-Communist Kuomintang (KMT) government’s wartime capital of Chongqing, not far from where she grew up. In 1945, her superiors arranged a cover marriage with a fellow CPC agent named Peng Yongwu. Although Peng was already married to another woman, the pair grew close, and in April 1946 Jiang bore him a son. She later told the brother of her husband’s other wife that they would sort out the complicated three-way relationship “if the revolution is successful, and if we’re all still alive.”

Jiang continued her activities after the end of WWII and the recommencement of China’s civil war. Peng was killed in 1947. A year later, Jiang herself was arrested. While detained at the Sino-American Cooperative Organization in Zhazidong, on the outskirts of Chongqing, her fellow inmates gave her the nickname “Sister Jiang.”

Then, on Nov. 14, 1949, as the victorious People’s Liberation Army neared the outskirts of Chongqing, Jiang was taken from her cell and executed. She was 29 years old.

Before she died, Jiang managed to smuggle out a letter. In it, she acknowledges that her death may be close and entrusts her son to the family of Peng’s first wife. “If the worst should happen, I leave Yun (her son) to you. I hope you will teach him to follow in his parents’ footsteps, to devote himself to building the new China, and to fight until the very end for the Communist revolution.”

There is no doubt Jiang was a hero; but there’s also no shortage of revolutionary martyrs from this chapter of Chinese history. What sets Sister Jiang apart is how her story was told.

The first major attempt to do so came over a decade after her death, in the 1961 historical novel “Red Crag.” The book’s authors, Luo Guangbin and Yang Yiyan, were comrades-in-arms and cellmates of Sister Jiang. Unlike her, they were lucky enough to be rescued, before spending the next decade novelizing their experiences. The story, jam-packed with scenes of high drama, fearless guerrillas, and feckless traitors, became a literary sensation.

Sister Jiang plays an important role in “Red Crag.” If you had to sum up her fictionalized personality in one word, it would be “steadfast.” There are two crucial moments involving Sister Jiang in the book. In the first, she realizes that the severed head suspended in a wooden cage at the entrance to the city belongs to her husband. Despite her immense grief, she stays composed and doesn’t break her stride. The other is when she refuses to give up her comrades, even under torture. Here, the book has her deliver one of the most famous lines in revolutionary literature: “These spikes are but bamboo,” she declares. “The will of the Communists is made of steel!”

It was a powerful portrayal of revolutionary spirit, but Sister Jiang was just one of number of memorable characters in “Red Crag.” Indeed, she hardly stands out in a cast of heroes ranging from spymaster Hua Ziliang to “Turnip” Song and the woman known as “Double-Gun Grandma.”

It wasn’t “Red Crag” that cemented Jiang’s legend, but a Red opera. And like all legends, some details were burnished. In the process, Jiang was transformed from a hardened guerrilla into a “red plum blossom” — a tough but beautiful feminine ornament to Mao Zedong’s revolution.

It was 1962, just a year after the publication of “Red Crag,” when the League of Literary and Artistic Workers of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force decided to take Sister Jiang to the stage. Liu Yalou, the then-deputy minister for defense and commander in chief of the PLA Air Force, personally oversaw the process. The seasoned general later explained the reasoning behind his choice at the 1963 Air Force Art Creation Conference: “Chairman Mao said that an uncultured army is a foolish army. We must not only engage in warfare, but also engage in culture.”

General Liu set extremely high standards. After a year of writing, the opera’s composers showed Liu their first draft. Much to their surprise, it was rejected out of hand, with Liu demanding they start again from scratch. After 20 painstaking revisions and two years, “Sister Jiang” finally premiered in Beijing in September 1964. Like “Red Crag,” it immediately sparked a frenzy, selling out wherever it went.

To this day, “Sister Jiang” is still considered a classic of Chinese opera, and it’s been adapted to opera styles from all over the country — including Yu, Chao, Yue, and Jing — as well as TV series and films. But for all the differences across these mediums, Jiang’s image has remained essentially the same as the one Liu and his team sculpted six decades ago. Indeed, the Jiang described by our hypothetical interviewee above isn’t the historical Jiang Zhujun at all, but their handiwork.

The greatest difference between the operatic Sister Jiang and her portrayal in “Red Crag” or her real-life historical self is her beauty. The real Jiang Zhujun was short and not remarkably attractive. Onstage, however, Sister Jiang is the embodiment of contemporary Chinese ideals of female beauty. Her outfit, with its blue, red, and white color scheme, is iconic and eye-catching. Her hairstyle is that of a female student during the 1919 May Fourth movement — a look synonymous with knowledge and progress.

This beauty balances the hardness of the historical Sister Jiang. The opera’s central song, “In Praise of the Red Plum Blossom,” uses that flower as a metaphor for the combination of toughness and delicate charm that coexist within the character.

Conveniently, “In Praise of the Red Plum Blossom” also echoes a poem written by Mao Zedong just a few years before. Playing on a classic poem in which the plum blossom symbolizes melancholy and an aloof disposition, Mao reframes the flower as a symbol of the optimistic Communist revolutionary spirit: “She craves not spring for herself alone; to be the harbinger of spring she is content. When the mountain flowers are in full bloom, she will smile, mingling in their midst.”

There is no clear evidence that the song “In Praise of the Red Plum Blossom” is directly related to Mao Zedong’s poem. Yan Su, who was in charge of writing the script, chalked the parallels up to artistic serendipity. Judging from the order in which they were made, however, there is a distinct possibility that the opera’s creators were slyly paying tribute to the Great Helmsman. One of the lyrics, “righteously blooming toward the sun,” certainly points in this direction: At the time, Mao was widely referred to as “The Red Sun.”

Whether intentionally or not, the song turned Sister Jiang into the personification of Mao’s plum blossom — and an ideal Communist. Nor was Jiang’s beauty the only artistic license the dramatization team exercised. Take the show’s most iconic scene, for example. Sister Jiang and her fellow inmates are so excited upon hearing the news of the official founding of the People’s Republic of China that they embroider the country’s newly designed flag in their prison cell. The scene is so famous that “embroidering a red flag” remains synonymous with a show of loyalty, even today.

But while the scene is based on an actual historic event, it wasn’t Sister Jiang who made the flag. Rather, it was Luo Guangbin, her fellow inmate and one of the authors of “Red Crag.” In the middle of the night on Oct. 7, 1949, Luo and some other inmates used leftover rice grains to glue yellow straw paper cutouts of stars onto a red safflower quilt. The opera’s writers chose to romanticize the story and attribute it to Sister Jiang. Instead of Luo, Sister Jiang and several young female inmates are shown chanting, “The thread is long and the stitches are dense; their number as great as our devotion,” as they knit together the symbol of their new nation.

It’s a revealing choice. In China, needlework is inextricably tied to feminine virtue. Countless songs, poems, novels, and operas describe women sewing clothes for their families. Having the female revolutionaries embroider together was an easy way of conveying to the audience that they had not totally abandoned traditional virtue. Only, the object of these women’s love and allegiance wasn’t their fathers, husbands, or children, but rather the New China. As in “Red Crag,” the complexities of the real Jiang’s romantic life are downplayed.

On the surface, this may appear contradictory. Communist and socialist movements have always been committed to advancing women’s liberation, so why do their portrayals of progressive women always feel anchored in patriarchal traditions?

But such apparent contradictions are inevitable. In a country with deep cultural and historical foundations, no radical revolutionary regime can completely ignore tradition. Sister Jiang’s commitment to the Communist revolution was unquestioned, but the manner in which she became an icon highlights the dual nature of Chinese revolutionary culture. Under the surface of anti-traditionalist, radical politics lies an ocean of customs and practices that must be harnessed if the revolution is to stay afloat.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editor: Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Wang Zhenhao and Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)