How Chinese in the US Are Talking About Black Lives Matter

On May 31, less than a week after the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer sparked nationwide protests against institutional racism and police brutality, an open letter penned by Eileen Huang went viral on Chinese social media. In it, the Yale undergraduate criticized fellow Chinese Americans for a perceived lack of solidarity with both the protestors and victims of racism more broadly.

Huang’s letter was not the only reaction to the ongoing protests that was widely shared on the Chinese internet, however. In a very different piece, read over 1 million times on ubiquitous social media app WeChat, a popular U.S.-based Chinese lifestyle blogger claimed her daughter had been cyber-bullied by her classmates for not posting a message in support of the protests. She went on to ask whether Chinese Americans had “the right to remain silent.”

Floyd’s death was not an isolated incident, and the protests it sparked are a continuation of the country’s Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which seeks justice and an end to over-policing. Although not directly implicated, Chinese communities in the U.S. are talking about, debating, and participating in these events, just like many around the country. Yet by-and-large they remain split in their attitudes toward protestors and their demands: the result of ideological, educational, and societal differences, as well as a deep generational divide.

In WeChat discussion groups popular among first-generation Chinese Americans who prefer consuming Chinese media, discussions of the BLM protests have tended to focus on their violence. Users were furious at the sight of stores being looted and destroyed, arguing that protests are no excuse for attacking innocent people. They worried the same might happen to Chinese-owned businesses, as it did in the Los Angeles Koreatown neighborhood in 1992, when residents rioted after four police officers were acquitted of violently beating Rodney King.

Others — especially those who grew up in the United States, or who are more comfortable with English-language sources — tend to be more supportive of the protestors’ aims, such as racial equality and an end to police violence. For them, the ideas of equality and liberty are key to a better society. Many have expressed a willingness to speak up and stand together with African Americans to fight for justice and equity, arguing the protests are necessary to raise awareness and push for fundamental changes.

These second-generation views are now being picked up, translated, and republished on Chinese-language social media, where they can be read by the first generation.

Even just among U.S.-based Chinese social media users, the responses have not always been positive. One thing many first-generation arguments have in common is a core belief that structural inequality does not exist, and that not all forms of inequality can be attributed to racial discrimination. According to this view, Chinese immigrants endured hardships and obstacles when they came to America, but successfully realized the American dream through “self-reliance.” If Chinese can overcome racism, why can’t African Americans?

Critics of Huang’s piece, for example, complained the author overgeneralized Chinese Americans as “racist,” while dismissing the achievements of Chinese Americans by saying they’re the result of the group’s status as “privileged” minorities within the U.S. racial hierarchy, rather than the hard work and perseverance of past generations.

One notable article, written by an immigrant in direct response to Huang’s letter, went further, accusing elite American educational institutions of “brainwashing” the country’s youth and turning them into “extreme leftists” who only care about identity politics. This view is common on Chinese social media, where users compare protestors and leftist young people with Cultural Revolution-era Red Guards.

A member of the first generation myself, I think both sides have raised valid points, and I recognize the complexity of the issues involved. I see the protests as an opportunity for Chinese Americans to engage in a dialogue and break down some of the walls between groups whose media and language preferences are markedly different.

But dialogue isn’t enough. Instead, both sides should seize this chance to effect real changes in the Chinese American community. Many first-generation immigrants came to the U.S. for an education. That should extend to educating themselves about the history and ideology of racial discrimination and the structural issues that perpetuate racial inequality in the United States. The younger generation, on the other hand, needs to learn more about the hardships faced by their parents — and in the case of second-generation immigrants, more about the culture and history of their parents’ home country.

More importantly, as a racial minority, Chinese Americans should show solidarity with African Americans and other minority groups. Although Chinese Americans and African Americans do not share a history of slavery and segregation, they have both experienced forms of systemic racism. We should be aware of our own prejudices and biases toward other racial and ethnic groups and recognize that all minorities share common adversaries: racism and white supremacy.

Chinese Americans are becoming more involved in public affairs in the United States. Sometimes, that comes with an expectation of action. Not everyone is comfortable with that fact yet, but even some of those who don’t support the protests volunteered to clean up the streets afterward. A few even brought their children, seeing it as an opportunity to educate them about citizenship. It’s a way to show they care about where they live, even if they don’t feel comfortable directly participating.

As for the right to remain silent, rather than treat it as an excuse, those uncomfortable with speaking up should consider practical ways to help African Americans in their struggle that go beyond chanting, “Black lives matter.”

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

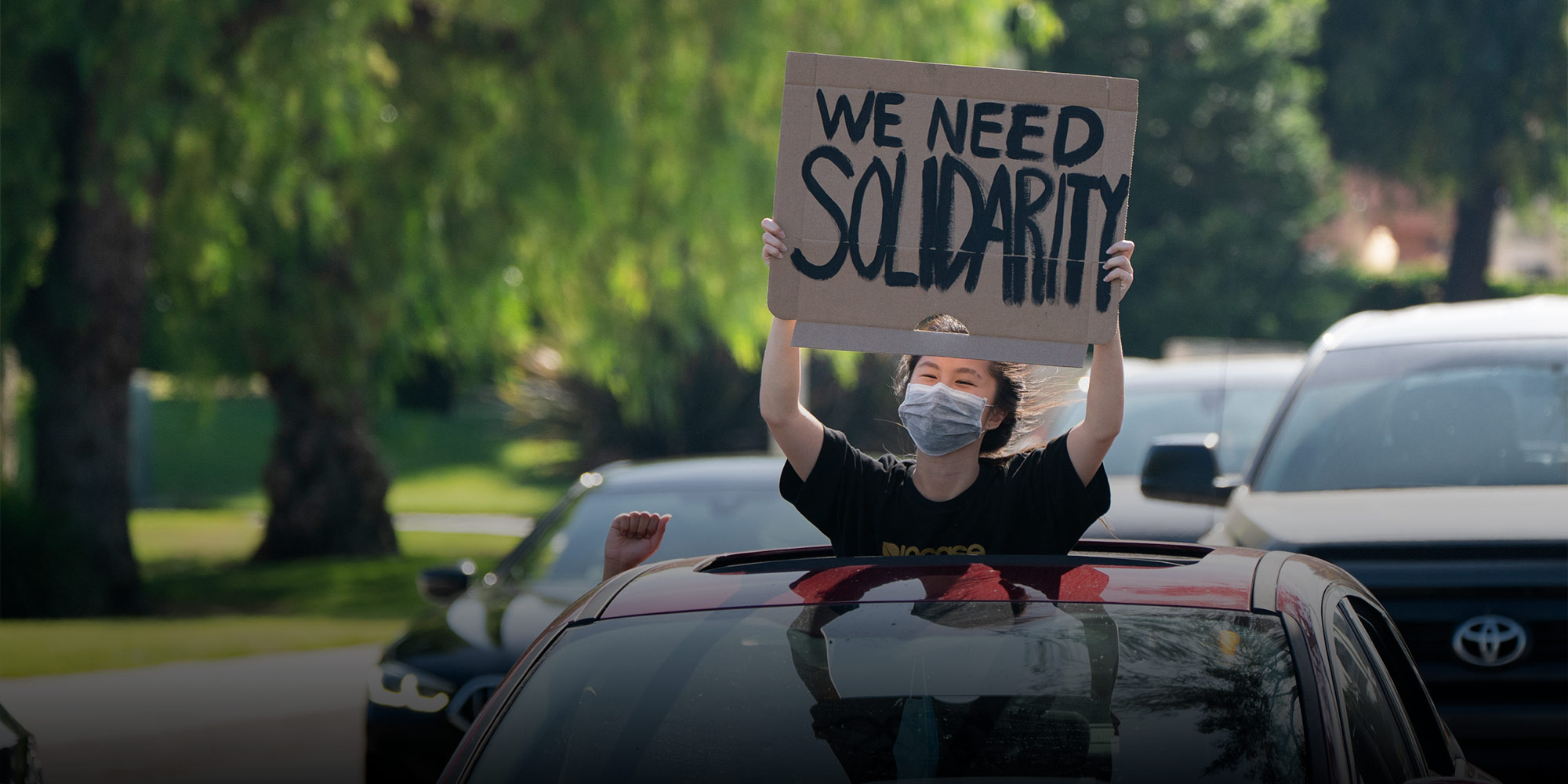

(Header image: A woman holds a poster in support of marchers during a demonstration in Los Angeles, May 31, 2020. Qian Weizhong/People Visual)