Redesigning Robocop for a Pandemic

This article is part of an ongoing series in which experts will analyze the role of science and technology in epidemic response and control in China and around the world.

“Please wear a mask, pay attention to personal hygiene, and avoid crowded places. If you feel unwell, seek medical assistance promptly.”

Such warnings have become an all-too-familiar refrain in recent months. They’re broadcast over loudspeakers, sent through text messages, and plastered on billboards. But if you’ve recently visited any of a handful of airports, high-speed rail stations, shopping malls, hospitals, or residential communities around China, you may have heard it emanating from a very unfamiliar place: a patrol robot.

My company released a line of these machines in the first half of 2016, well before this pandemic. Prior to January of this year, they were generally used to complete industrial tasks considered dangerous for humans, such as detecting leaks in nuclear power plants or phosphine gas residue after granary fumigations.

But after the COVID-19 outbreak in the central city of Wuhan spread nationwide, my team held an emergency meeting to see if there was any way we could help. Within a few days, we came up with a plan to upgrade our robots to make them better suited for infectious disease control work. The new “COVID-19 models” were ready to manufacture the moment we resumed work on Feb. 3. A week later, they were on the front lines of the epidemic.

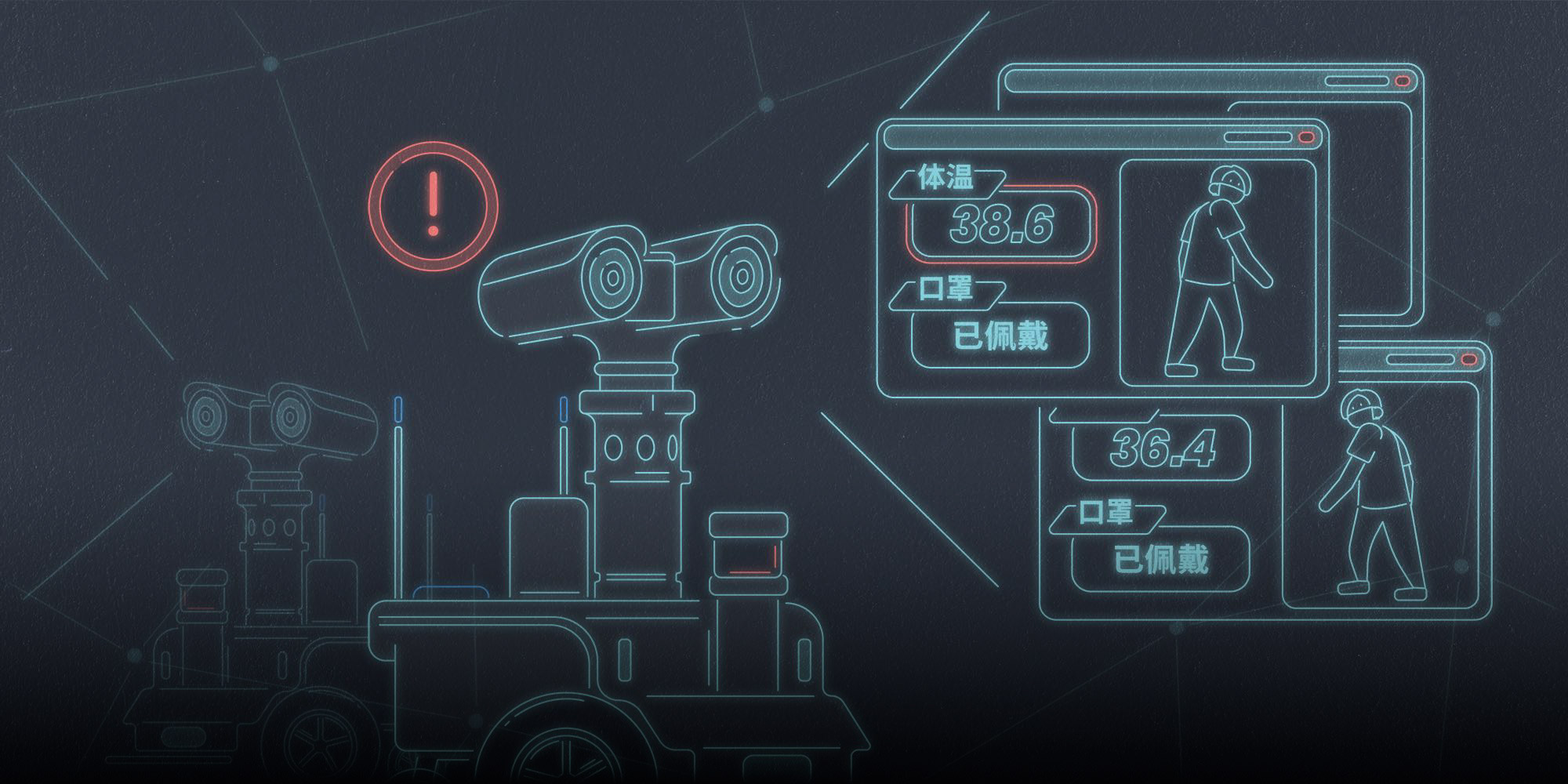

Of course, we made them capable of far more than just wandering about, bleating out warnings. In addition to their five high-definition cameras, they can measure the body temperature of 10 people at once, identify whether pedestrians are wearing masks, and even issue friendly reminders to those who aren’t.

The coronavirus’ rapid spread has given new impetus to China’s robotics industry. Over the past four months, hospitals have used robots to screen visitors’ temperatures, distribute food to patients in isolation wards, and sterilize high-risk areas such as intensive care units and operating rooms. Outside the medical sector, our campaign for social distancing has sparked a rise in “zero contact” business models, including unmanned shops and automated delivery services.

This trend is unlikely to disappear once COVID-19 is under control. As China’s demographic dividend dwindles, labor costs rise, and machinery gets cheaper, the widespread adoption of automation and robotics is merely a matter of time.

Globally, China is neither a clear-cut leader nor a laggard in the field. In 2019, the global robotics market was valued at $29.4 billion, and grew by an average of 12.3% annually between 2014 and 2019. The Chinese robotics market, which grew by about 21% per year during that span, finished the five-year stretch accounting for a little less than one-third that sum. If that growth is to continue, however, we need a clear understanding of our strengths and weaknesses as an industry.

In terms of the former, the Chinese government is vigorously promoting and investing in technological development, including artificial intelligence, 5G, blockchain, cloud computing, and big data. This focus on what officials have termed “new infrastructure” will also help stimulate the rapid growth of robotics. Take 5G, for example. 5G-capable robots are already in use in many areas, and as the networking technology develops, its high bandwidth and low latency will allow more of the processing to be conducted in the cloud, meaning the robots themselves will require less internal processing power. This will lower costs while increasing stability.

Second, by virtue of being based in the so-called world’s factory, Chinese robotics firms have access to a secure and relatively complete manufacturing chain. Robots are complex creations, requiring high levels of both software and hardware expertise. This takes time to accumulate, but there are signs that the domestic industry is moving up the value chain. The country’s increasingly sophisticated manufacturers now boast the ability to produce almost every component used in our devices, with the exception of a few hardware items, such as central processing units.

At a time when pandemic-related travel restrictions have upended global supply chains, our ability to keep production lines running is proof of how important this advantage can be. We have taken steps toward localizing the production of radars, controllers, and motors with an eye toward further reducing our overall manufacturing costs.

Finally, robots are already being used in a wide range of places in China, from airports to government offices. This is generating a tremendous amount of data which can be used to drive further technological evolution and train algorithms.

Despite these advantages, however, the Chinese robotics industry still faces critical problems when it comes to talent recruitment, research, patents, and access to capital.

Although many schools have established robotics majors, the curricula remain overly broad, and insufficient to meet the needs of industry players. Meanwhile, companies often shy away from basic theoretical research, in part because of the costs involved and the amount of time it takes to see results. The government needs to step up and help plug this gap, whether through academic or research and development funding.

Then there is the lack of patents owned by Chinese firms, and, equally important, the industry’s poor understanding of other countries’ patent regimes. China’s robotics industry only began applying for patents in the 1990s. Not only did this put the country behind the rest of the world, China’s technology also paled in comparison. If Chinese companies want to export their products, they need a basic understanding of importing countries’ patent rules, but there is currently no advisory body capable of helping firms manage this challenge.

Lastly, there’s access to capital. Starting a robotics company without funding for at least the first five years is risky. But that’s a tough bar to clear when a firm can blow through anywhere from 60 million to over 1 billion yuan a year ($8.5 million to $141 million). Of the many startups that rushed into the nascent patrol robot sector in 2018, for example, very few remain today.

Luckily, the outstanding performance and widespread application of robots during the ongoing pandemic appears to have attracted the attention of investors — a slim silver lining during this dark time. As the underlying technology improves and the market continues to grow, I believe we will start to see more robots in restaurants, schools, and in our own homes. The future is bright, and startups have been presented with a golden opportunity to speed up the industry’s development. We should seize it.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Wang Zhenhao for Sixth Tone)