Law Professor’s Quirky Lectures Attract Millions of Online Fans

China’s National Judicial Examination, or fakao, isn’t the most obvious source of entertainment.

For anyone aiming to enter the legal field, they must hope they’re among the 10% or so who pass the test, often described as the single most difficult exam in China. Mastery of 17 subjects is required to unravel the complicated legal cases presented to those brave enough to attempt it.

One criminal law professor and fakao tutor has become a celebrity of sorts thanks to his engrossing teaching style and enthusiastic fan following. After creating an account on video-sharing site Bilibili earlier this month, Luo Xiang racked up 1.7 million followers in just five days.

In Luo’s lectures, which are recorded during class and later posted online, the professor brings criminal law to life through creative storytelling and deadpan humor — a style some fans have compared to crosstalk, or traditional Chinese comedic performance. As Luo relays real and made-up legal riddles to his class in a thick Hunan accent that many find endearing, he constantly changes the pitch and volume of his voice, vacillating between serious and absurd, and asking rhetorical questions while giving his viewers time to reflect on how they would respond.

Luo’s complex legal anecdotes involve a regular cast of fictional characters, such as the nefarious Zhang San — a made-up-sounding name analogous to John Smith. Zhang is so comically diabolical that he has ascended to meme status among fans, who even made him his own Bilibili account. Over the course of Luo’s lectures, Zhang has poisoned people, scammed prostitutes, died of fright from the sound of fireworks while bathing in a pond, robbed people using a piece of poo, gone to prison for pouring scalding water on a tree, and been cuckolded by his wife.

The stories are often linked to real cases, but with an added twist of dark humor. In one example inspired by the 2018 Chongqing bus accident that killed 15 people, a bus driver gets into an argument with a passenger who refuses to pay the fare. After the passenger hurls a bowl of noodles at the driver’s face, the driver becomes distracted eating the noodles while fighting with the passenger, and rams into a crowd of people. Some made-up examples later became real-life cases, such as that of a woman who paid a man to rape her housemate but ended up getting raped herself when he mistook her for his target.

Other scenarios that have yet to manifest in reality include that of the Amsterdam sex worker who provided fapiao, or invoices commonly used to write off expenses, to Chinese tourists (Would they be valid?) and the man who was injured by his ex-mother-in-law while breaking up a fight between his current and former wives.

“So how should we judge this case?” a solemn Luo asks his rapt audience at the end of each outlandish story.

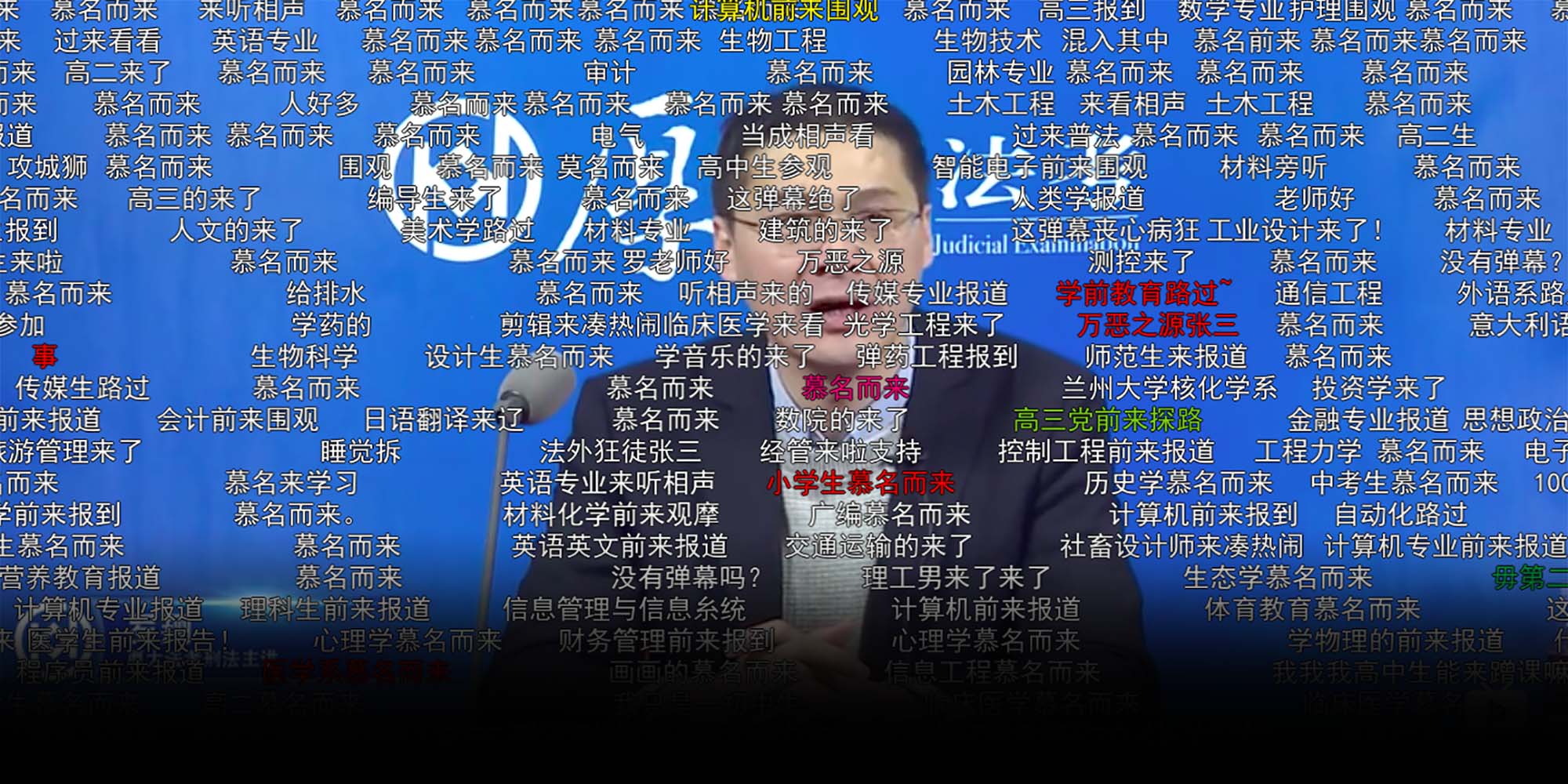

Luo’s star rose before he had any inkling that he was famous. His fakao exam prep lectures began circulating on Bilibili in 2018. By the next year, Bilibili content creators were mixing best-of reels and guichu music videos from Luo’s lectures. At the start of one 44-minute lecture posted in December 2018, Luo can barely be seen behind the barrage of “bullet screen” comments streaming over the video, many written by students simply declaring their intended major.

Fans have reported becoming obsessed with Luo’s lectures, watching them for hours on end, and some say they’ve been inspired to pursue careers in law. “I’ve been listening to Luo’s lectures constantly since I became pregnant,” says a fan quoted in a Guangdong Communist Youth League article. “His voice is already in my DNA: When my baby comes out, it’ll be able to recite China’s criminal law backward.”

Although the jokes may be what reel viewers in, Luo’s lasting appeal lies in the reverence with which he treats legal matters, as well as ethics and public welfare. Amid all the absurdity, he peppers in quotes from serious historical figures like Plato, Newton, and the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi.

“On every fakao exam, there are always a few exceptionally complicated questions that even students who have studied well typically can’t answer,” one WeChat article quotes Luo as saying. “That’s because they studied so much that they lost their humanity.”

In one of Luo’s most famous real legal anecdotes — the so-called cesspit case — he relates how a young female cadre was attacked by a man trying to rape her at a remote hillside location in the 1980s. After failing to fend him off or summon help with her screams, she pretended to surrender and suggested they move to more level ground. She lured the man near a latrine pit and shoved him into the filth as he was undressing. The man made three attempts to extricate himself, but the woman stomped on his fingers each time, causing him to sink back in. The man died a most undignified death, drowning in the liquid putrescence.

In the real legal case that followed, Luo explains, it was argued that the woman’s first foot stomp had been “justifiable self-defense” under Chinese law, while the other two times counted as “ex post facto self-defense” — meaning the woman should bear some responsibility for her would-be rapist’s death. Luo argues that this determination is a classic example of legal professionals trying to make a rational judgment with the full benefit of hindsight, rather than simply thinking from the perspective of an ordinary person in that situation.

“Never, ever, judge a case while standing in the future. … Would you (in the same position) grab a rock and smash his head in? You would,” Luo says, pausing to let his words sink in. “Just be sure not to get excrement on your clothes,” he adds.

Despite all the attention he’s getting, Luo has no desire to become a celebrity, and hopes students see the legal field as more than just a source of jokes and memes.

“I don’t want to become famous. I just want to be someone who treats his profession with respect and reverence,” Luo wrote on microblogging platform Weibo. “This idea is what excites me, while also instilling a sense of peace.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: A screenshot from Bilibili shows viewers’ “bullet screen” comments scrolling across one of Luo Xiang’s lectures on law.)