Meet the Mortals Behind China’s ‘God Songs’

BEIJING — Song is the name, and song is his game. While some musicians take months to compose, record, release, and promote a track, Song Mengjun and his team can get it all done in a matter of hours.

The 29-year-old hit-maker has plenty of tricks to keep the ideas flowing. His team monitors China’s most popular streaming apps for trending search terms, and then brainstorms ideas based on these keywords. In April, when a group of astronomers announced they had captured the first image of a black hole, Song put out his track “Monster From the Black Hole” within 24 hours, ensuring that it would ride the crest of internet searches to the top of the charts.

Song’s company, Beijing Yunmao Culture Ltd., releases roughly two songs each day. Despite their heavy workload, the staff does not appear stressed when Sixth Tone visits the studio. Most of the dozen employees wear bulky headphones, so the studio is quiet as their fingers flick between piano and computer keyboards. Every now and then, a few will drift into the stairwell for a smoke, but they always return to their desks before the cigarette burns down to the butt.

The music that Yunmao makes doesn’t fit into any one genre in particular: The company cheerfully pivots to whatever the market desires on any given day. But Chinese listeners refer to these viral, flash-in-the-pan hits as shenqu — “god songs”.

There’s nothing divine about the production process. Yunmao operates like a mass manufacturer, building god songs on an assembly line. Song demonstrates the process for Sixth Tone in his studio: First, he borrows the backing track from a well-known song by Taiwanese singer Jay Chou, mumbling the rhythm into a mic. Then, his co-worker puts it together with a melody on the keyboard, adding in other audio samples from their vast database of demos, while another two compose lyrics on their laptops. In less than half a day, there’s already a rough cut.

Every track is quick to make and quick to get stuck in your head. “No one will give you a minute,” Song says, explaining that songs only have seconds to capture an audience’s attention. His infectious tunes cut right to the chorus, because he believes his target youth demographic likes to rush to the climax.

This is music for the age of short attention spans, instant gratification, and search engine optimization. And it’s lucrative: “9277” — one of Yunmao’s top hits — raked in almost 10 million yuan ($1.55 million) in 2018. On major music streaming platforms like Kugou, god songs often outperform releases from big-name pop stars when it comes to listens and downloads in the long run. More clicks mean more cash.

China’s music market is growing fast. There are approximately 33 million paid music subscribers in China, according to the managing director of Sony Music in China, Andrew Chan, in a 2019 report released by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) which also stated that in 2018, China became the seventh-largest music market in the world. The streaming market in particular is skyrocketing, with a year-over-year growth of 35% in 2018, according to the IFPI.

For Song’s team, licensing what they consider high-quality music, such as for TV shows, only makes up 30% of Yunmao’s income. The company’s biggest revenue stream comes from licensing their god songs. But while god songs are amassing plays and profits, they’re also attracting critics who claim they’re dumbing down music with their brainless lyrics and borrowed beats.

It’s dirt off his shoulder for Song. “The era of doing offline music has passed,” he says. “The future is about cashing out online.”

♫ But you don’t really care for music, do you? ♪

Song used to sing a different tune when he was a student at the Xinghai Conservatory of Music in southern China’s Guangdong province. “I used to detest god songs,” he recalls.

He performed more than 400 gigs as an undergrad, while also moonlighting at a local radio station to boost his marketing and promotion skills and undertaking a second major in art management. When he dropped his first album, he was proud of his work — but sales were meager.

Disillusioned, he moved to Beijing and started working at a record company, where he noticed that the most popular songs weren’t what he would have considered good music. “The market doesn’t care about your academic standards,” he says. He learned how to apply digital-first, market-driven pragmatism to music production, and the rest is history.

Independent musicians like Beijing’s Ma Yuyang complain that this mentality is squeezing them out of an already difficult market. “When more people give their attention to god songs, it seriously impacts us indie musicians who use real soul to make music,” the 30-year-old says.

Ma has put out two albums in the eight years he’s been in the indie music scene. He’s sold around 3,000 copies in total — not bad for indie releases, he says. But when he later collaborated with a god song writer on one single, to his surprise it became a big hit that quickly boosted his fame and fortune. Nonetheless, Ma still looks down on musicians who churn out formulaic hits in the pursuit of profit. He attributes the success of god songs to Chinese audiences’ static tastes which lead songwriters to play it safe instead of following their creative instincts.

Song disagrees: He argues that too many artists are self-absorbed, obsessed with expressing their own feelings instead of adapting to the new opportunities created by speed, connectivity, and changing music consumption patterns. Where once people settled for listening to whatever was played on the TV and radio, now there are more people actively accessing music through all kinds of platforms. “You cannot control what listeners are exposed to,” he says, and more than ever, it’s consumers driving the trends rather than music professionals.

Music promoter Yang Junlong goes further. “China has a population of 1.4 billion. Why would you force dishwashers or doormen to like your choice of music?” he says.

♬ Rake it up, break it down, bag it up ♪

Making the music is one thing. Marketing it is another. And that’s where hype man Yang excels: “Learn to Meow,” the first release from his studio, dominated the Chinese music market in 2018. Despite having a simple refrain — “Let’s all learn to meow, all together meow, meow, meow, meow, meow” — sung by relatively unknown performers Xiao Feng Feng and Xiao Pan Pan, it quickly won the hearts of millions of Chinese netizens, making it to Billboard Radio China’s top 10 list of the year’s most popular music, as well as finding many fans overseas.

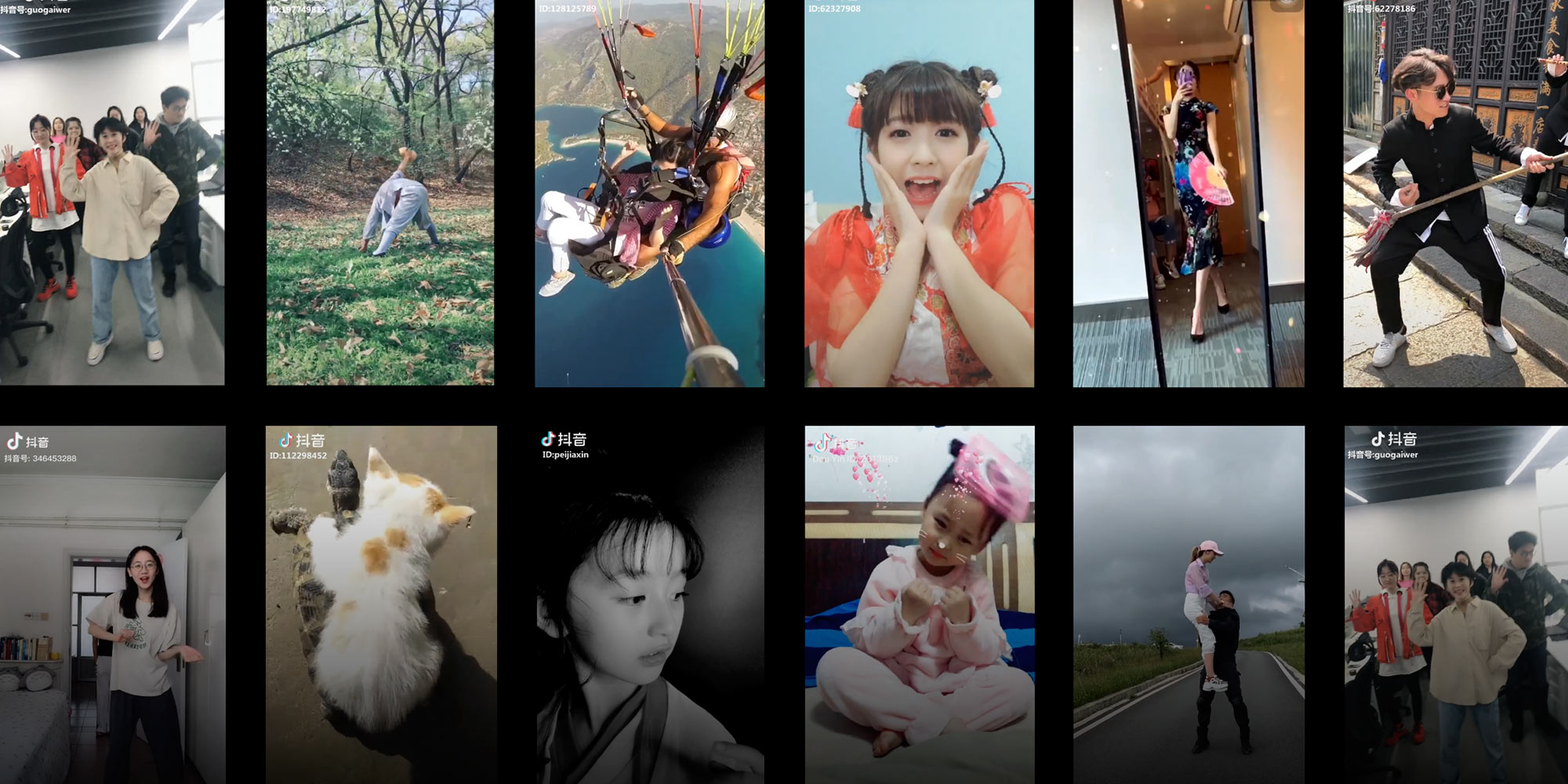

The song’s success was in large part thanks to Yang’s viral marketing campaign. He commissioned half a dozen social media influencers to come up with a simple dance routine to accompany the song. Then his team tweaked their choreography and hired even more popular influencers to perform the final version and upload their clips to short video platform Douyin — which operates overseas as TikTok. In two days, “Learn to Meow” surged from 2,000 to 80,000 views on Douyin.

Soon, it seemed everyone on Douyin was meowing, pawing the air, and tweaking their whiskers. The trend quickly caught on with TikTok users in South Korea and Japan, and YouTubers even created cover versions of “Learn to Meow” in Indonesian, Ukrainian, Tagalog, and several other languages.

Yang utilizes various tactics for promoting music, but his core strategy always involves audience participation — or rather, meme-ability. He believes a good god song should always have an irresistibly catchy 15-second refrain that can be sampled for background music. That helps it spread on China’s largest short video platforms, Douyin and Kuaishou.

Though the two sites share 60% of their user base, they require slightly different strategies, according to Yang. Strong rhythms are more important for Douyin — a 15-second video platform that is more popular with worldly, well-off millennials and is known for memes such as beauty transformations and pranks — while Kuaishou, with more rural working-class users, favors songs that tell a story.

Even so, penning god song lyrics isn’t too strenuous, according to Ding Zhaoyu. The 24-year-old college student is both an indie musician and a part-time god song lyricist for a music agency. “What they require is pretty routine,” she says. “I think even people who barely know music could do it.” While she believes that a “real musician” should try to make a statement or extend their practice beyond replicating a formula, she also recognizes that a job’s a job. Indie music alone isn’t enough to pay the bills.

To some critics, however, the problem with god songs isn’t just a matter of taste. While Song was a god in the god song scene, it was his songs that were famous, not him — until a plagiarism accusation made him notorious.

♫ I walk the line ♪

In 2016, music critic Deng Ke accused Song of copying Jay Chou’s song “Nocturne” with a nearly identical rhythm in “The Distance of a Centimeter”. Millions of loyal Jay Chou fans then waged an internet war that pushed Song’s name into the headlines.

Song explains that while he used a similar backing track — which Song calls a “beat” — the resemblance did not exceed eight bars, which is commonly considered fair use.

Guo Chunfei, a senior partner specializing in copyright law at Tiantai Law Firm, tells Sixth Tone that there’s no law specifying the eight-bar rule in China, although it’s often discussed at law conventions. “Rulings on music plagiarism are always subjective, based on the judge’s decision,” Guo says. Judges make rulings with the help of music specialists like critics, professors, or a third-party assessor, Guo explains, but the criteria vary from case to case.

Music copyright disputes overseas are equally contested. In 2018, Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’ “Blurred Lines” was judged to have infringed the copyright of Marvin Gaye’s 1977 song “Got to Give It Up”. The pair was ordered to pay Gaye’s estate nearly $5 million and ongoing royalties, following a five-year legal battle that saw more than 200 musicians file an amicus brief in support of Thicke and Williams because they felt the judgment would adversely affect the industry.

“All music shares inspiration from prior musical works, especially within a particular musical genre,” said the document, signed by artists such as Linkin Park, Weezer, and Jennifer Hudson. “By eliminating any meaningful standard for drawing the line between permissible inspiration and unlawful copying, the judgment is certain to stifle creativity and impede the creative process.”

The debate over fair use and inspiration rose again this summer, when Katy Perry, her collaborators, and her record label were asked to pay nearly $2.8 million because of similar instrumental elements between her 2013 hit “Dark Horse” and 2008’s Christian rap song “Joyful Noise.” For Chinese god song makers, however, the issue has been ongoing since the first wave of the viral hits. In 2006, singing group Phoenix Legend was accused of plagiarizing six bars from a folk song in their tune “Above the Moon.” After two years, the court ruled that it counted as plagiarism, though the plaintiff only won 20,000 yuan in compensation — 10% of what they had asked for.

“The cost of plagiarism is still quite low,” Guo says, adding that, while China’s copyright law has expanded to match international standards, the penalties are much less severe. When plaintiffs win, the payouts are often only a couple hundred yuan — not even enough to cover the attorney fee.

Wang Shu, a composition lecturer at Shanghai Conservatory of Music, says that there’s nothing wrong with drawing inspiration from existing works but that artists must acknowledge their sources and aim for originality. Wang says that Song’s music is like fast food, which might hit the spot for contemporary audiences, but is likely to change as musical appreciation grows alongside with living standards in China.

“Art should guide people instead of just catering to the market’s appetite,” Wang says.

Song believes he can do both. He’s been investing 30% of his company’s profits into training promising singers who he believes have star potential beyond the god song formula. But he also takes pride in his ability to wrangle the holy trinity of music, math, and marketing.

“Nowadays, making music is just like trading stocks, looking at the data all day,” he says.

Editors: Qian Jinghua and Hannah Lund.

(Header image: Screenshots of “god songs” on the app Douyin. Re-edited by Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone)