Camera Above the Classroom

BEIJING — Jason Todd first discovered his school’s secret on the internet.

It was late September 2018, less than a month after high school had started. Jason was idly scrolling through his news feed on the Chinese microblogging site Weibo when he saw a trending hashtag — #ThankGodIGraduatedAlready — and clicked it.

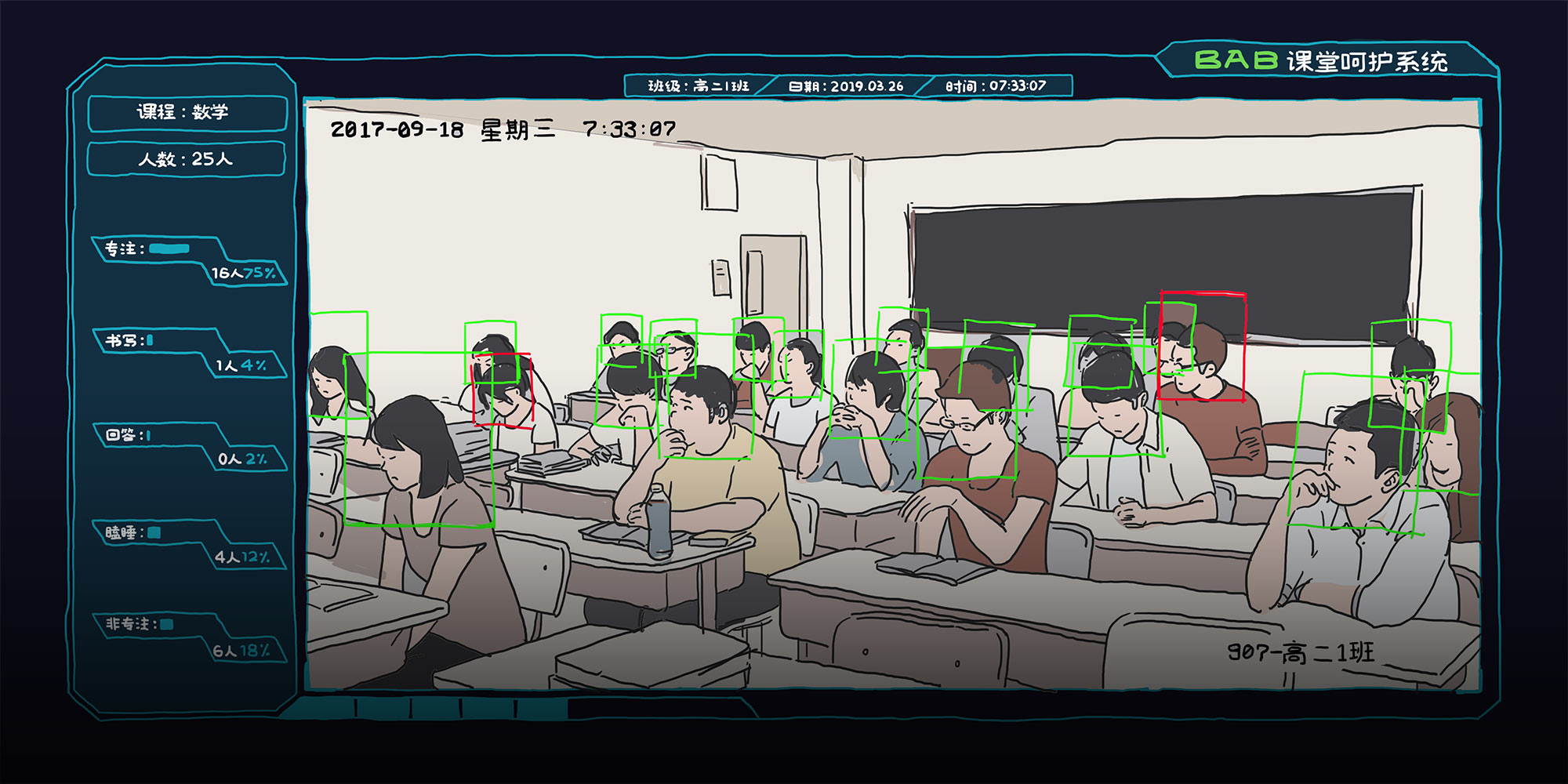

Under the hashtag, someone had posted a photo depicting a bird’s-eye view of a classroom. Around 30 students sat at their desks, facing the blackboard. Their backpacks lay discarded at their feet. It looked like a typical Chinese classroom.

Except for the colored rectangles superimposed on each student’s face. “ID: 000010, State 1: Focused,” read a line of text in a green rectangle around the face of a student looking directly at the blackboard. “ID: 000015, State 5: Distracted,” read the text in a red rectangle — this student had buried his head in his desk drawer. A blue rectangle hovered around a girl standing behind her desk. The text read: “ID: 00001, State 3: Answering Questions.”

Jason thought the photo was a scene from a sci-fi movie — until he noticed the blue school badges embroidered on the chest of the familiar white polos worn by the students. It was exactly the same as the one he was wearing.

“F**k, no,” he thought.

Jason is a 16-year-old student at Niulanshan First Secondary School in Beijing. He wears a pair of black-framed glasses and likes to read DC comics so much that he chose to use the name of one of his favorite characters for the sake of anonymity. If he hadn’t seen that image online, he wouldn’t have questioned the presence of the tiny white surveillance camera installed above his classroom’s blackboard. After all, Niulanshan never informed him — or any of its 3,300 other students — that facial recognition cameras were capturing their every move in class. In fact, it’s unlikely that the combined 28,000 students in the six other schools testing the same system know they are part of China’s grand artificial intelligence (AI) experiment.

In July 2017, China’s highest governmental body, the State Council, released an ambitious policy initiative called the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (NGAIDP).

The 20,000-word blueprint outlines China’s strategy to become the leading AI power in both research and deployment by 2030 by building a domestic AI industry worth nearly $150 billion. It advocates incorporating AI in virtually all aspects of life, including medicine, law, transportation, environmental protection, and what it calls “intelligent education.”

Following the NGAIDP’s release, Chinese tech companies have rushed to secure government support and investor funding for various AI projects, several of which are being tested in Chinese schools. Over the past two months, I interviewed a dozen students in schools that have installed different “intelligent education” systems and spoke to tech entrepreneurs whose companies are developing the systems used in those schools.

While advocates claim that using facial recognition to monitor students’ in-class behavior can accurately assess attention levels and help them learn more efficiently, most students I spoke with had a different opinion. They showed concern that the school never asked for their consent before harvesting their facial data. One student expressed anxiety at the idea that the times he was caught slacking off in class would eventually be used to determine his chances of attending his dream university. Other students disconnected the cameras at their school before final exams in protest.

In addition, teachers and experts question the extent to which facial recognition systems can improve student performance. Experts say there are many technological, legal, and moral barriers to overcome before facial recognition can be widely deployed in Chinese education. But the government’s AI push is already introducing this technology before settling such debates, leading experts to agree that regulations on the technology urgently need to catch up.

“Class Care System”

n the upper left corner of that photo Jason found on Weibo, you can just make out the words “CCS Class Care System.” CCS is one of the flagship products of Hanwang Education, a subsidiary of Hanwang Technology. Hanwang is a household name for China’s younger generation. Growing up, they watched catchy commercials for the company’s text-to-speech reading pen on television. Today, Hanwang builds hardware and software products that provide facial and biometric recognition services and optical character recognition, as well as air quality monitors and purifiers. Hanwang Education was founded in 2014 as part of an initiative to expand the company’s market into China’s education sector.

At the research center, which occupies a nondescript, three-story house in a residential estate in northwestern Beijing, Hanwang Education General Manager Zhang Haopeng rushes downstairs to greet me. He’s a busy man, currently helming the deployment of CCS in partner schools across the country. Fortunately, he’s managed to find time for an interview.

If transitioning from text-to-speech pens to facial recognition technology seems like something of a quantum leap, it’s really not, Zhang explains. Recognizing a student’s facial expression and reading out handwritten notes are variants of the same thing: pattern recognition. To the machines, faces and handwriting are just data, and identifying them is all about spotting patterns. Since 2015, Hanwang Technology has also been using deep learning, a type of AI that mimics the brain’s analytical models, to buttress its existing technology. “Hanwang is at the forefront of pattern recognition,” Zhang says proudly.

At first, Hanwang struggled to monetize its cutting-edge facial recognition products, which it only used for commercial purposes, such as face scanners that log employee work hours or smart billboards that tailor their advertisements to audience gender. Zhang tried unsuccessfully to push Hanwang into the education sector, marketing interactive whiteboards and an “e-schoolbag” tablet that acted as a multipurpose textbook. But once China announced the NGAIDP in 2017, Hanwang finally found its niche: education analysis.

The plan’s “intelligent education” section describes in detail how China’s government hopes to use AI to boost the country’s education system. Zhang reads me one paragraph from the guidelines without stammering. “So detailed. It’s like they wrote it with a [facial recognition] product right in front of them,” he says.

Zhang, who keeps a framed photo of his smiling children on his desk, says that parents in China are yearning for more information about their children’s school performance. It’s a country where test scores can make or break an individual’s future. Visit any Chinese primary school at the end of the day, he says, and you’ll see parents bombarding teachers with questions. “Did my son fall asleep during English class again?” he says, mimicking the questions parents might ask. “Did my daughter and her deskmate talk too much during class? Should we separate them?”

Zhang says that for most Chinese parents, school is the only time they let their kids out of their sight. “Parents worry when their children aren’t around. They want to take care of every aspect of their lives,” he tells me. “But the teacher only has one pair of eyes.”

“Do you know the two types of students teachers pay the most attention to?” Zhang asks. “The smartest and the naughtiest.” Hanwang’s CCS technology was born from the desire to care for every kid in the classroom, even the “often-ignored, average students,” he adds.

Zhang shows me one of Hanwang’s CCS cameras. It’s the size of a mandarin orange, but it can recognize all 50 students in a classroom. “Just five years ago, this kind of technology was unimaginable,” he says, explaining how the camera homes in on students’ unique facial features to identify each individual — and in a much less obtrusive way than a fingerprint or iris scanner. “We can identify a person’s face from just one picture, even when the frame size is as low as 640 x 480 pixels,” Zhang says.

Even though CCS hasn’t received official approval from China’s Ministry of Education yet, it’s already been implemented as a pilot project in seven schools around the country since its launch in December 2017. In these schools, a white, dome-shaped camera is installed above the blackboard at the front of each classroom. Once per second, it takes a photo of the entire class and sends the footage to a server where Hanwang’s deep-learning algorithms identify each student’s face and classify their behavior into five categories: listening, answering questions, writing, interacting with other students, or sleeping. The algorithms then analyze each student’s behavioral data and give them a weekly score, which is accessible through a mobile app.

Zhang takes out his phone and logs into a user account on CCS’s mobile app. The account belongs to a teacher at Chifeng No. 4 Middle School in the city of Chifeng in northern China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The interface allows teachers to view scores for every student in class. A green down arrow appears next to the student’s score when it decreases, and a red up arrow when it increases. A bar graph shows how many minutes the student spent concentrating, sleeping, or talking in class.

“The parents can see it, too,” Zhang says, tapping on a student’s name. “For example, this student’s report shows that he rarely volunteers to answer the teacher’s questions in class. So his participation in English class is marked as low. Number of questions answered: one,” Zhang reads from the AI-generated report. “This week, the student spent 94.08 percent of class time focusing. His grade average is 84.64 percent. He spent 4.65 percent of the time writing, which was 10.57 percent lower than the grade average.”

“What’s your takeaway from the report?” Zhang asks, before once again answering his own question. “This student doesn’t like to answer questions in English class, so maybe his parents and teacher should do something.”

On the app, teachers and parents are also able to see up-to-date photos of the classroom and check students’ behavior, just like in that photo with the colorful rectangles. Zhang plans to expand CCS to 100 schools around the country by the end of 2019 and, eventually, he wants to create a nationwide platform for all schools.

“Now do you understand the ‘care’ part of our product name? Not a single student is missed,” Zhang says, smiling.

He leads me to a tiny room where two dusty CCS servers sit under a desk. One, which costs 60,000 yuan ($8,900), can analyze facial recognition data from five to six classrooms simultaneously. The other can monitor 20 classrooms and costs 150,000 yuan. Wiring a single classroom costs around 30,000 yuan. Zhang won’t tell me how much it costs per school, but if the high school I went to installed CCS in its 36 classrooms, it would cost at least 1.38 million yuan.

But so far, none of the schools using CCS have paid the staggering price. The government has offered financial incentives to local education bureaus to encourage them to use big data and AI — incentives that cover the installation costs. “[Local education bureaus] couldn’t be happier to implement the [AI development] policy,” Zhang tells me.

But if the social media reaction to CCS is anything to go by, the technology isn’t convincing everyone. I ask Zhang about the fearful messages posted under last year's leaked photo of the children at Jason Todd’s school. “People are overreacting,” Zhang says with a slight smile. “CCS doesn’t violate the students’ privacy. We don’t share the reports with third parties, and you see that on the in-class pictures we send to the parents, all the faces other than their child’s are blurred out.”

Before I leave, I ask Zhang one final question: “Do the students know?”

“Of course. You can’t use it without their consent,” he replies.

“What do they think of it?”

“They hate it.”

Zhang told me that at Chifeng No. 4, students unplugged the cameras before the day of their final exams. The cameras captured everything until the last moment.

#ThankGodIGraduatedAlready

wo hours away from Hanwang’s research center, I peep through the backdoor window of Jason Todd’s biology class. Most of the 30-odd 15- and 16-year-old students are listening carefully, taking notes from time to time. Some gaze out the window. Three nap with their heads buried behind stacks of books.

For the most part, it’s a run-of-the-mill classroom. The huge blackboard at the back of the room is decorated with drawings of red lanterns, snowmen, and fireworks to celebrate the coming Lunar New Year. Motivational quotes from Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein hang on the walls. However, there are three cameras installed in the classroom, including a small white one right above the blackboard.

Once the students notice me, a murmur of noise starts to build in the classroom. “Pay attention!” the teacher says, knocking on the blackboard. But nothing stops a classroom of curious teenagers, and it remains noisy until the bell rings for recess.

Before the students have a chance to leave, another teacher enters the classroom and announces: “Those of you who didn’t do the face sampling last time, go to the music room right now. Hurry.” The students empty out.

A group of six boys who completed the process stay in the classroom, handing out homework as their classmates leave. None of them, other than Jason, know what the face sampling was for — the teacher didn’t tell them. I ask what the cameras in the classroom are for. “To see if we are behaving well in class?” one tells me, although he says he isn’t sure. The students say the cameras have been there since they started school in September.

Since discovering that photo on Weibo, Jason’s been observing the cameras installed in the classroom, trying to guess their functions. The smaller one at the front is used for facial recognition, he deduces from the picture on Weibo. The bigger one at the back of the classroom is used for livestreaming, judging from the angle of the video he previously spotted on his teacher’s laptop. He’s not sure about the third camera on the window side of the classroom, though he thinks it’s a backup.

Jason’s teacher, Guo Yuzhuo, a short-haired woman with a calm voice and over 20 years of teaching experience, confirms his speculations. The two other cameras, besides the one used for Hanwang’s CCS, were installed by the school itself. The teachers use the camera in the back to check the class in real time, without having to peep through the backdoor window and interrupt the students. Guo says they tend to notice right away that teachers are watching, as I’ve experienced.

According to Guo, the teachers use Hanwang’s CCS occasionally to check for any abnormal statistics in the AI-generated weekly reports, but so far, the school hasn’t told the students about the system. She says the school will eventually inform the parents “when it’s time to do so,” explaining that they want to avoid possible obstructions from reluctant students and parents. Guo’s answer contrasts with Hanwang Education manager Zhang’s reassurances that the system wouldn’t be used without students’ consent. Dong Wencheng, a Hanwang Education technician responsible for installing CCS in Beijing, says it’s the school’s job to inform the students, not Hanwang’s. “We suggest the schools ask for the students’ consent before using CCS,” he says, “but it’s just our suggestion. If they don’t, there’s nothing we can do.”

Back in the classroom, my questions about the cameras evoke curiosity among the boys. Jason tells them everything he knows. There is a gasp, followed by silence. “I want to smash it,” one boy says. “Shhh!” Another boy shakes a warning glance at Hanwang’s camera behind us. “What if the camera just captured everything?”

The rest of Jason’s classmates are still unaware they are being watched by Hanwang’s CCS camera. But some 1,400 kilometers away at Hangzhou No. 11 Middle School in eastern China’s Zhejiang province, the students know exactly what the cameras in their classrooms are capable of.

Hangzhou No. 11 uses the “smart classroom behavioral management system” developed by Hangzhou-based Hikvision, the world’s largest manufacturer of video surveillance equipment. Like CCS, Hikvision’s facial recognition technology also monitors students using cameras installed above each classroom’s blackboard. In addition to in-class behaviors, which are divided into six categories — reading, writing, listening, standing up, raising hands, and lying on the desk — Hikvision also identifies seven different facial expressions: neutral, happy, sad, disappointed, angry, scared, and surprised. The data is used to generate a student’s score, which is displayed on a screen installed on the wall of each classroom. Each class’s overall attention level also displays on a huge screen in the hallway for the whole school to compare and rank.

Hangzhou No. 11’s facial recognition system made domestic and foreign headlines last May. Unsurprisingly, the program was met with criticism, but the school’s principal, Ni Ziyuan, said he believed the system would boost educational standards. “It’s the same as teachers having an assistant,” he said in an interview. Unlike a teaching assistant, facial recognition cameras don’t interrupt the class, and capture the most natural status of the students, he claimed. The school’s vice president, Zhang Guanchao, also said in later interviews that the system has had positive effects since its implementation.

However, the students feel differently about the system. One anonymous Hangzhou No. 11 student I found on the internet tells me she felt shocked and scared when the teacher demonstrated the system in front of the whole class. “The camera can magnify 25 times of what it captures,” she says, adding: “It can see not only your face, but the characters on your notebook. After all, it’s from Hikvision.” Another student tells me his classmates were totally “crushed” after the installation of the system. Because the system gives students a public score, he and his classmates don’t dare nap or even yawn in class for fear of being penalized, an incentive that doesn’t necessarily increase focus on learning. In fact, the students spend their time focusing on staying awake until class ends. “Nobody leaves the classroom during the class break,” he says. “We all collapse on the desks, sleeping.”

Online, China’s “intelligent education” systems have faced critical scrutiny. Under the #ThankGodIGraduatedAlready hashtag, which has over 23 million views, Weibo users have compared Hanwang’s CCS to George Orwell’s dystopian sci-fi novel “1984.” In a forum discussing Hangzhou No. 11’s system on Zhihu, China’s Quora-like online platform, the comments are uniformly critical. “The smiling face you see on a monkey in a circus is not a smile of joy, it’s a grimace of fear,” one user wrote. “Can you manage to focus in class when you know there’s someone standing behind the classroom? Let alone knowing there’s a camera.” And when students from other schools asked why their teachers started collecting facial data, someone responded: “The whole country is advocating ‘intelligent education.’ It’s probably your principal who wants to add glory to his career accomplishments.”

When I ask to visit Hangzhou No. 11, Vice President Zhang Guanchao declines my request but insists the facial recognition system is a good thing, assuring me over the phone that the system doesn’t violate students’ privacy, since it only records facial data rather than displaying the students’ faces. In addition, he sends me a promotional video set to lively background music, featuring a student in the school’s uniform break dancing around the campus, scanning his face to pay for food at the canteen, borrow books from the library, and buy water from a vending machine. It turns out that the “smart classroom behavioral management system” is just one part of Hangzhou No. 11’s “five-star smart campus initiative,” which implements facial recognition technology throughout the school’s campus.

Back at Niulanshan, the students who went in for face sampling are still not finished. I head to the music classroom, where I find the seats rearranged so that only 16 are in the center of the classroom. Four A4 pieces of paper with the numbers 1 to 4 on them are stuck to different points on the blackboard. Hanwang’s Dong Wencheng tells the students to look at each number for 15 seconds, switch seats, and do it all again.

The students were updating their facial data, Dong explains. When they move their heads to look at the numbers, CCS’s camera is able to capture their face from different angles. Schools normally capture the students’ facial data at the beginning of the semester and update it every couple of months. “These teenagers look different every two months. Puberty, you know!” Dong laughs.

I ask him about the facial recognition system used at Hangzhou No. 11. “I don’t know if you’ve seen Hikvision’s product,” Dong says about his company’s competitor, “but I am not impressed by it. They only scan the classroom every 30 seconds, 80 times in a 40-minute class. We do it once a second, 2,400 times in total!”

Jason’s teacher, Guo, tells me she’s quite impressed by CCS so far, although the teachers don’t use it that often. “It’s good, but it’s machines, not humans,” she says, adding that there are some features that need to be more “intelligent” — the reports are mostly numbers, but the teachers want to know more about what these numbers mean and reflect.

Niulanshan’s principal, Wang Peidong, who has over 40 years of teaching experience, is also dismissive of CCS. “It’s not very useful,” he says. “You think a teacher standing on a podium needs AI to tell her if a student is sleeping in class?”

“Then why is it still used in your classrooms?” I ask.

“Zhang Haopeng is an alumnus of our school. He wants to do experiments here, so we let him. We don’t need to pay for it anyway,” he says, already walking away to get to his next meeting.

A Booming Business

n May 27, 2017, AlphaGo, AI developed by Google’s DeepMind, defeated Chinese Go player Ke Jie — the best human Go player in the world. Chinese-American entrepreneur Kai-Fu Lee refers to this as China’s “Sputnik moment.” Indeed, China’s best player losing an ancient Chinese chess game to AI developed by a Silicon Valley tech company later became the catalyst for the country’s drive to close the gap on AI technology.

Less than two months after Ke Jie lost to AlphaGo, the Chinese central government issued its ambitious development plan to improve the country’s AI capabilities. By the end of 2017, China’s venture capital investors had responded to that call, pouring record sums into AI startups in all sectors, including education, health care, and finance. In total, Chinese capital made up 48 percent of all global AI venture funding for 2017, surpassing the United States for the first time.

According to Wang Shengjin, a professor at Tsinghua University’s Department of Electronic Engineering, facial recognition is currently the technology’s most feasible and mature application, based on a greater potential for widespread use. This is due to the technology’s ability to utilize deep learning, which has turbocharged the pattern recognition capabilities of machines.

As mentioned above, CCS uses deep-learning algorithms to analyze the identifying patterns of a person’s face. Wang tells me that, traditionally, this is done with the facial feature detection method called Eigenface, which can be unreliable and significantly limited to facial angles, distances, and resolution. “If you laugh or cry, the distances and shapes of your facial features change completely,” Wang says. But by utilizing deep learning, systems like CCS avoid these limitations. Professor Wang explains that this method essentially studies a multitude of different, labeled images and learns to identify a specific subject under all possible conditions.

It’s a complex process, but one thing is clear: Training machines to identify a person’s face with deep-learning methods requires massive amounts of data. Wang tells me that Silicon Valley-based tech companies and research institutes are still in the lead when it comes to advanced AI academic research. But China has one advantage: massive amounts of data. According to The New York Times, China had around 200 million public surveillance cameras as of July 2018; the country is expected to install 626 million by 2020. Not all of these surveillance cameras have facial recognition capabilities, but the images they gather could provide huge amounts of data to train deep learning-powered facial recognition tools like CCS.

The utilization of deep learning algorithms allows for three broad types of facial recognition: 1:1, 1:N, and M:N. The 1:1 type is often used at transportation hubs to verify that a person matches their ID photo, for example. 1:N is used to identify one person from a group of people, like when clocking in at the office. And M:N, the most complex of the three methods, is used to identify multiple people within a larger group, such as spotting criminals on the streets.

These methods create various market opportunities for facial recognition, the most obvious being policing and public safety. For example, in one instance, police used AI-based technology to identify and arrest 25 criminals at a beer festival in Qingdao, a city in eastern China’s Shandong province. However, many companies are also adapting this technology for commercial use, such as KFC and search engine giant Baidu, who have collaborated to develop facial recognition technology that can customize food orders by identifying a customer’s age, gender, and mood.

Last December, I visited a facial recognition tech company called Ovopark based in Suzhou, a canal city in eastern China’s Jiangsu province. Ovopark recently partnered with Meituan — China’s answer to Yelp — to help brick-and-mortar businesses install facial recognition cameras in their stores. When a customer enters the store, the camera uses facial recognition to identify if the person is a VIP customer or a frequent visitor. The camera captures the shopper’s shopping history and stores it, allowing the sales assistants to provide a more customized shopping experience. Ovopark CEO Zhou Youwen tells me the facial recognition cameras at Ovopark can also provide customized shopping suggestions.

In Ovopark’s showroom, I stand in front of the camera, which identifies me as an angry 40-year-old female — 15 years older than my actual age. “Try a bigger smile,” Ovopark Sales Manager Wu Yingxia suggests. This time it works. The angry face emoji next to my face on the screen changes to a happy one, and the machine correctly identifies me as 25 years old. I have to maintain my awkward smile, otherwise the emoji will immediately revert to an angry face.

Another huge screen fitted with a mounted camera tells me which celebrity I look like and scores me based on my perceived attractiveness — the higher the score, the bigger the discount. Ovopark sells this product to shopping malls for entertainment. I score 95 out of 100. Wu tells me Ovopark adjusted the scoring criterion so that it doesn’t give customers too low of a score — she scores a 93. “It’s just for fun, after all,” Wu says as her score flickers in bright blue lights on the LED screen with the message: “You look like an angel.”

It makes me think of the students at Hangzhou No. 11 Middle School.

A Modern-Day Panopticon

ccuracy isn’t much of a concern with the more frivolous applications of facial recognition, like the one I tested at Ovopark. But when the same technology is used in identification-sensitive fields like policing or finance, the resulting inaccuracies could lead to wrongful accusations and convictions, fraud, or theft. For instance, in November 2018, Chinese authorities wrongly accused entrepreneur Dong Mingzhu of jaywalking after a streetside camera identified her face in an ad on the side of a bus.

Everyone I talked to at Hangzhou No. 11 Middle School and Niulanshan First Secondary School expressed skepticism about the accuracy and reliability of facial recognition technology. As part of their smart campus initiative, Hangzhou No. 11 uses Hikvision’s facial recognition cameras to record the students’ attendance rate and for on-campus payments, but it doesn’t seem to work very well. A female student told me that Hikvision’s system is particularly inaccurate for girls. “Once we change our hairstyles or wear glasses, the camera won’t recognize [us] anymore,” she says through text. The different lighting and angles of their faces also slow down the recognition process, making the lines during lunch extremely long.

“The technology is not perfect yet,” admits Professor Wang Shengjin, “but you can’t always wait for technology to become perfect before using it.” Wang believes that practice makes perfect: The more we use facial recognition technology, the more problems we discover and solve, ultimately leading to perfected facial recognition systems.

The laws aren’t perfect, either. In fact, there are none. “No, there is no law regulating the use of facial recognition technology or other biometrics data in China,” says Hu Lin, an assistant law professor at Shanghai University of Economics and Finance. He tells me that, since there is currently no law prohibiting facial recognition in China, there’s nothing illegal about what these “intelligent education” systems are doing.

But there’s a bigger question: Even if it’s technologically possible and legally acceptable for schools and tech companies to use in-class evaluation systems powered by facial recognition, should we use them?

I ask He Shanyun, an associate professor of education at Zhejiang University. She tells me that the schools and “intelligent education” developers need to prove that the data they’re collecting is reliable for measuring educational performance. “If a student was burying his head in his desk but was actually looking for a pen, or if two students were talking but to discuss the teacher’s question, it’s not fair to classify them as being distracted,” He says.

Facial recognition technology would also need to consider the “cultural context” of people’s facial expressions and behaviors, He points out. She gives the example of a silent student who’s not answering questions or showing any expression on their face. “People from some cultures are more likely to express themselves through facial expressions and actions, but Chinese are normally more reserved,” He says. She also notes that classrooms are like mini ecosystems, where countless human interactions happen simultaneously in a small space. Each student brings their own culture, family values, and experiences. None of these factors are easily analyzed by capturing facial expressions. Machines are still less adept than humans at understanding cultural context and behaviors, according to Professor He. “We should encourage the use of new technology in daily life, but when it is used as a tool to evaluate individuals, more caution is needed,” she tells me.

Hangzhou No. 11 also seems to realize the technology’s inadequacies. Over the phone, Vice Principal Zhang Guanchao tells me the school has updated its facial recognition system and will no longer evaluate facial expressions. The students will now only be given a negative score if they’re captured lying on the desk.

But even if facial expressions accurately reflect students’ educational performance, does that justify the schools and developers using facial recognition on students? The answer, Professor He tells me, comes down to China’s philosophy on education.

“If our society thinks education is something that can be evaluated by statistics such as exam scores or in-class performance,” says He, “then don’t blame the schools for using algorithms to determine if you are a good student or bad student.”

She agrees that the intention of “intelligent education” is positive. As the NGAIDP guidelines suggest, the purpose of the initiative is to assist teachers in developing customized teaching methods and study plans for every student. But the current use of facial recognition technology in the classrooms worries her. “These statistics aren’t completely useless, but relying too much on them is not good for teaching,” He says.

“If in the end, the technology is only used to rank students by how many times each one yawns and punish them for doing so, it’s indeed a waste of the technology,” she says, suggesting that teachers should be trained on how to appropriately analyze and use the data as a reference rather than as decisive criteria. “We can’t push back the tide, but we should at least start trying to manage it.”

A focus on inaccurate statistics also worries most of the students I talked with about CCS. In particular, Jason Todd is afraid that his score will eventually be used to decide whether he is able to attend his dream school. Professor He believes schools and teachers should get the students’ consent and inform them of their intentions before using the data to evaluate performances.

Most students at Niulanshan First Secondary School still don’t realize how teachers know everything that happens in the classroom. And although the students at Hangzhou No. 11 know their every wink and yawn is captured and expressed as a score, the school never asked for consent. Neither school has published any information on their websites indicating that they obtained the consent of students or parents prior to installing the system. Jason Todd even checked with his mom, who confirmed the school never asked for her permission, either.

According to law professor Hu Lin, the lack of consent in the use of the surveillance systems creates an imbalance of power. “The schools hold the power to evaluate, punish, and expel,” he says. “The parents won’t sacrifice the students’ futures by standing up against the schools, which leaves the students in the most vulnerable position.”

Hu refers to the panopticon, a circular prison discussed by French philosopher Michel Foucault in his book “Discipline and Punish,” in which inmates are observed by a single watchman but cannot tell if and when they are being watched, forcing them to act as if they are always being watched. To Hu, using systems like CCS will have the same impact, encouraging students to simply act like they’re behaving.

But Hanwang’s Zhang Haopeng isn’t worried. “We are all role-players in certain circumstances,” Zhang says. “You can pretend for one hour, two hours. But if you can make it work by pretending to listen to class for eight hours a day, I respect you.” Even if students are simply acting like they’re listening in class to pass the CCS, maybe one day it will become a real habit rather than role-play, Zhang tells me.

The increasing use of facial recognition technology is already raising concerns in Western countries. In July 2018, Microsoft’s president and chief legal officer, Brad Smith, wrote an open letter calling for U.S. federal regulation of facial recognition technology. In February, Amazon followed suit. San Francisco is considering banning its city agencies from using facial recognition, and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has categorized facial data as “sensitive personal data,” which affects how it can be handled.

But the current situation in China is worrisome. The government’s “intelligent education” initiative has attracted other companies eager to profit from bringing surveillance technology into China’s classrooms. According to a report published last December by state-run newspaper Global Times, 10 schools in southwestern China’s Guizhou province now use chip-equipped “smart uniforms” developed by a local company to track the exact locations of their students to encourage better attendance rates. A high school in southern Guangdong province has recently received criticism for forcing students to wear “smart bracelets” that also track their location. And a Massachusetts-based startup called BrainCo — founded by Chinese entrepreneurs — has signed a deal with a Chinese distributor to provide schools with 20,000 headsets that monitor student concentration levels by reading and translating their brain signals in class.

More schools and education bureaus are jumping on board, too. The Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education issued guidelines for developing “intelligent education” last May, calling for more schools to build “smart classrooms” that are capable of “collecting in-class behavioral data.” It also plans to subsidize more schools and companies to bring these AI-driven initiatives into classrooms.

Despite the shortcomings and ethical criticism, Hanwang Education’s Zhang Haopeng remains confident in the CCS initiative. “There have [always] been researchers in the academic field doing classroom behavioral observations. Do you remember in primary school, there were tutors occasionally sitting in the back of the classroom, taking notes and evaluating the teacher’s and the classroom’s performance?” Zhang asks me. “We just replaced them with a camera.”

On Lunar New Year, I text Jason Todd, wishing him good luck and following up to see whether his mom thinks his school should use CCS. His mom is right next to him, and he replies immediately. “She said yes, because she hopes the school will keep a better eye on us,” he writes, adding a string of emojis with bitter smiles.

I ask him to show his mom the classroom photo he discovered online — the one where each kid’s face is surrounded by a colored rectangle. A few minutes later, Jason texts back: “She says, ‘No way. It looks like a prison.’”

Illustrations: Wang Zhenhao; visual editor: Ding Yining; editors: Julia Hollingsworth, Chris Bolin, Clayton D’Arnault, and Matthew Walsh.

This article was published in collaboration with “The Disconnect.”