Artist Brings ‘Haha-Then-Aha’ Moments to China’s Gender Debate

SICHUAN, Southwest China — In most Chinese bookstores, there’s a section of bright pink books instructing women on how to be a good housewife or find a man before they hit 30.

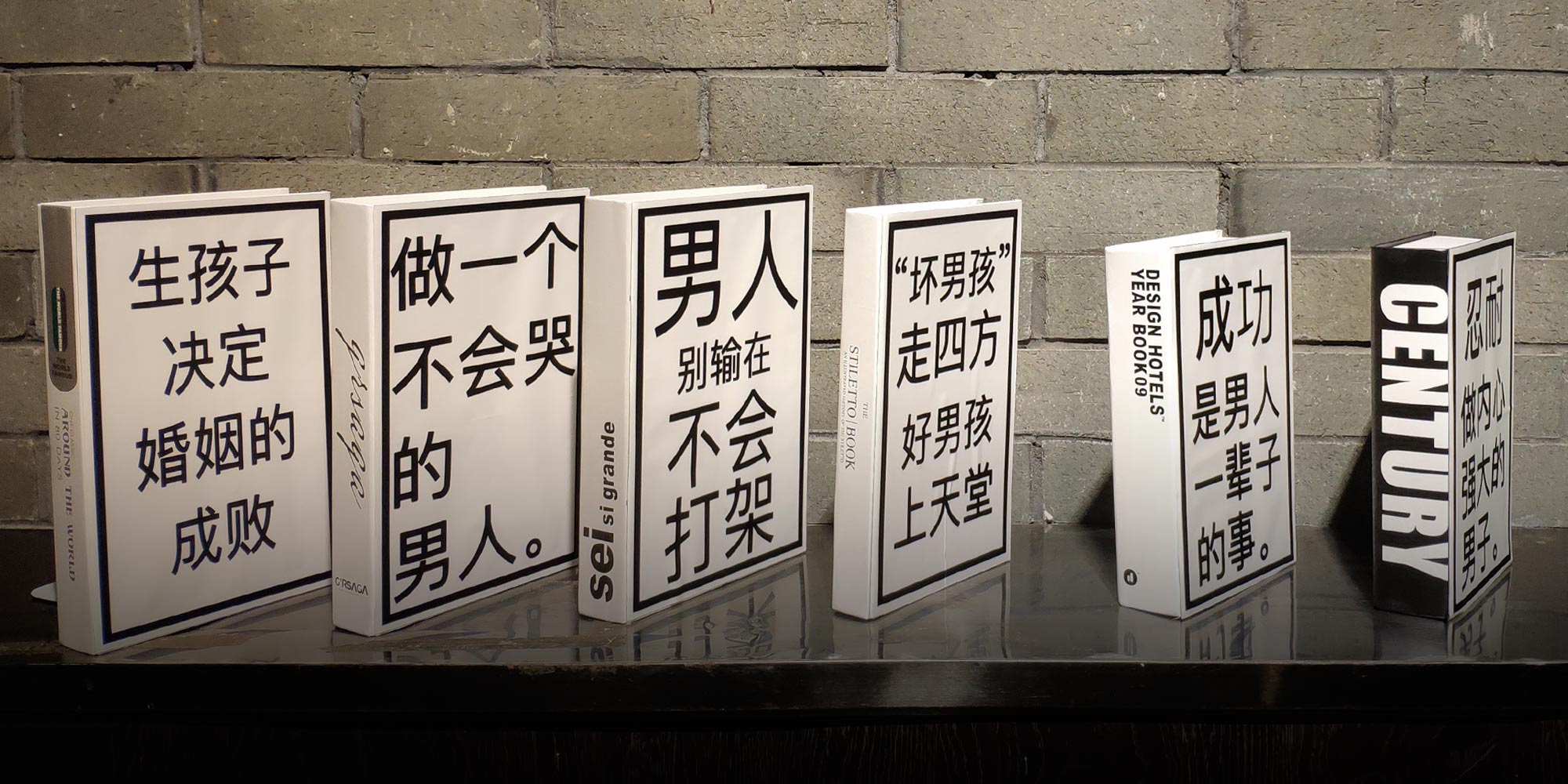

But at an out-of-the-way underground art space some distance from provincial capital Chengdu’s city center, there are how-to books of a different kind. “Be a Man Who Never Cries,” instructs one. Other titles include: “Men, Don’t Lose Arguments Because You Don’t Know How to Fight” and “‘Bad Boys’ Go Everywhere; Good Boys Go to Heaven.”

It’s a typically tongue-and-cheek part of artist Wu Kangyang’s latest exhibition, held in Chengdu in October. In another area of the industrial-style room with exposed brick walls, there’s a platform where men are encouraged to sit or stand and think about why men rape women, rather than asking women what they can do to keep themselves safe from rapists. There are large white posterboards, mimicking the instructional boards you might find in a “feminine virtues” class, except these have phrases like: “Virginity is a man’s best betrothal gift;” “Do not participate in dinners where women are present; problems could creep up on you;” “Be alert on the bus. Don’t give female hoodlums an opportunity to be indecent;” and “Giving birth to a boy is useless. A married son is like spilled water.”

Since Wu’s first exhibition on heterosexuality went viral in April, he’s become known for his works that first make his audience giggle, and then reflect. It’s a unique approach in China, where many still hold traditional views on gender, and if the issues feature in art at all, artists rarely take a lighthearted tack. Wu’s witty commentary on stereotypes is especially popular online, where it plays into a national gender debate that has repeatedly surfaced in recent years following news about harassment on public transportation, media misogyny, and misconduct in universities and workplaces. Wu’s even been given promotional support from NetEase, one of China’s biggest tech companies.

Born and raised in the city of Mianyang — about 130 kilometers northeast of Chengdu — Wu, now 29, developed his love of art while accompanying his mother, a retired textile worker, to the factory where she mixed colors. Despite his artistic bent, Wu caved to pressure from his parents to major in English, which they thought would make it easier for him to find work. When his classmates became teachers after graduation, Wu instead started his career in art and now works in a private art gallery. On the side, he makes money arranging holiday installations for shopping malls and follows his less lucrative passion of creating exhibitions on the issues of gender and sexuality.

It’s a subject close to home for Wu, who has known he was gay since middle school. Nevertheless, he’s never told his parents and doesn’t plan to, worried they’d isolate themselves from their friends out of shame. “Maybe they’ve already figured out that I’m gay, and it’s just that no one wants to talk about it,” Wu says. “I would feel relieved if I were to come out of the closet, but the reality might put them into a closet.” His mother and father, he says, are mostly interested in watching TV dramas and political news, respectively. They have little notion of their son’s popularity.

Wu’s latest show was inspired by an argument over China Central Television’s annual back-to-school gala, which featured a performance by a group of so-called little fresh meat entertainers — delicate, handsome, and often feminine young men. Parents criticized the national broadcaster en masse for imparting “non-masculine” and “non-positive and uplifting” values on their children. The discussion reached the highest echelons of Chinese public debate: While state news agency Xinhua said such “sissy pants” represent a “sick culture” that would negatively impact the nation’s children, Party newspaper People’s Daily argued modern society allows a diversity of interpretations of what it means to be a man.

Wu says he didn’t take the debate seriously until he noticed some middle-aged male curators that he admires share articles such as “Sissy Young Boys Lead to a Weak Country” on messaging app WeChat. “I was shocked and angry,” he says, adding that society puts pressure on men with expectations that they have a well-paid job, act tough, and don’t cry. “When ‘sissy pants’ becomes a trend, it challenges mainstream ideas and makes some people uncomfortable and anxious,” he tells Sixth Tone.

Wu decided to satirize women’s bookshelves and feminine virtues course posters because they were eye-catching and simple, making them perfect for getting his message across — and going viral on social media. But it was about more than just popularity: He wanted people to rethink their ideas.

On a chilly weekday during his six-day exhibition, visitors laugh out loud and take selfies with the installations, immediately uploading them to social media. Wu, who wears round, Harry Potter-style glasses and sports floral tattoos on his forearm, isn’t sure they’ve understood his intentions, yet he prefers not to explain his work to the visitors. “Everyone has their own views, and maybe their understanding is deeper than mine,” he says.

But plenty of people seem to get the message. Luo Zhihui, 23, just moved to Chengdu for a master’s degree. He identifies as gay and has read about Wu’s other gender-equality exhibitions on social media. This is his first visit. The art-lover describes himself as sissy, but it’s not a negative word in his mind. It’s just who he is. “I’m slim. I care about my looks, but it doesn’t make me less of a man,” he tells Sixth Tone after visiting the exhibition.

Luo says he’s been to a few other exhibitions calling for gender equality, but they all look too serious. Wu can’t agree more. “Many people think that when discussing social issues, they must use a kind of hateful resentment,” he says. “They must shout slogans and stand in opposition. I think this is a misunderstanding, which creates a greater communication barrier.”

Wu used a similar sense of humor in his April exhibition on heterosexuality. Visitors were presented with a “Chengdu Heterosexuals Map,” which shows the places in the city where straight men tend to hang out. Then, photoshopped news headlines: “Global Outbreak of Heterosexual Demonstrations, Anti-discrimination Fight is Everyone’s Responsibility;” “Celebrities Speak Out in Support of Heterosexual Rights;” “Heterosexual Marriage Has Been Passed, History has Been Changed.” The show was aiming to turn discourse on its head, posing a series of questions: What is heterosexuality? What is the origin of heterosexuality? How can you recognize someone who is heterosexual?

Once again, that exhibition had been inspired by the news. That same month, microblogging site Weibo purged LGBT-related comics and videos amid a crackdown on violent and “lewd” content. A few days later, the site backtracked after a public backlash. Wu, who is unimpressed by the efforts of LGBT groups in Chengdu, believes his art can help raise awareness about LGBT issues.

Sometime before noon during the October exhibition, Huang Xinya walks in. Believing that gender equality is an important issue, she decided to check it out after reading about it on Douban, an app for reviews of books, movies, and art. Huang, 24, says she is one of the many young women who are fans of the “little fresh meat” aesthetic. “I don’t understand why many people say they are sissy,” she says. “And even if they are, what’s the problem?”

With Chinese women becoming more independent and fighting for equality in all aspects of life, Huang says, “we can like any type of men we want, instead of longing for a tough and masculine man to take care of us.” Huang mentions the changing attitudes toward men wearing makeup: “Everyone has the right to make themselves look good, which has nothing to do with gender.” Plus, she adds, “there are more than just two genders, male and female, in the world.”

Joy Lin, the founder of Shanghai-based feminist organization We and Equality, finds many Chinese people still hold stereotypical views on how men and women should dress and behave. She mentions a “feminine virtues” summer camp held in eastern Zhejiang province last August which reportedly taught children that wearing revealing clothes would cause rape. A similar workshop held in northeastern China in 2017 taught married women to swallow their husbands’ insults and eschew divorce at all cost. At the same time, many schools in recent years have introduced masculinity courses that teach boys how to be “true” men.

Lin praises Wu’s use of irony in challenging mainstream beliefs. “It’s a smart way for spreading ideas and educating the public,” she says. “These ironic phrases first make people laugh, and then think.”

While Wu believes that Chinese society has become more aware and supportive of gender and sexual minorities, LGBT and feminism are still sensitive topics. The downtown mall that was the original venue for his heterosexuality exhibition backed out of hosting it, meaning he held it in a private art space instead. He was recently given a list of words that are unofficially banned by authorities, including “homosexual.” And although Chengdu — his home for over six years — has a reputation for being China’s queer capital, Wu believes this reputation is unfounded. People in Chengdu care about pandas — there’s a breeding center in the city — and will line up for hours to try a newly opened hot pot restaurant, but when it comes to gender equality and the LGBT movement, Chengdu trails behind cities like Shanghai and Beijing, he says.

“I’m trying to make Chengdu a better city by making people think about real issues in my own humorous way,” Wu says. “I hope one day when Chengdu is in the headlines, it’s for more than just cute pandas and tasty hot pot.”

Nevertheless, Wu’s work has already made some people change their minds. After seeing Wu’s success, the downtown mall venue realized they made a mistake. “[They] regretted canceling the exhibition after seeing it was that popular,” Wu says. “I then responded that they’re not very farsighted.”

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: A row of how-to books for men designed by Wu Kangyang to satirize women’s bookshelves at his exhibition in Chengdu, Sichuan province, Oct. 24, 2018. Fan Yiying/Sixth Tone)