The Three-Book Problem: Why Chinese Sci-Fi Still Struggles

BEIJING — In a small lecture hall packed with hundreds of people, a lone voice shouts: “Now we are comrades!” Others join in, the chant bouncing off of the walls as they repeat the slogan in unison.

Despite the crowd’s fervor, it’s not a gathering of loyal Communist Party supporters. Instead, it’s an event for Earth-Trisolaris Organization (ETO) members, celebrating May’s 10th anniversary of the first installment of “The Three-Body Problem” by Chinese novelist Liu Cixin. In Liu’s famous series, the ETO helped communicate with a highly advanced, invading alien civilization. In real life, however, it’s merely a fan club with a tongue-in-cheek name.

In the front row of the China Science and Technology Museum’s chanting crowd stands Yao Haijun, a tall and slender 52-year-old who can’t stop smiling. It’s a joyful time for Yao: Around a decade ago, he helped lay the foundations for the immense “Three-Body” universe, which went on to become the best-known Chinese sci-fi series, and the first to win an international award. For others though, the anniversary shows how far Chinese sci-fi still has to go: Despite the success of “Three-Body,” a China-made sci-fi movie has yet to hit the silver screen.

So what went wrong?

“The Three-Body Problem” dates back to 2006, when Yao — then an editor of the monthly Science Fiction World magazine — received a draft of what would become the first installment of Liu’s epic trilogy. He’d read Liu’s previous stories, but this time Yao knew that he had something extraordinary in his hands. The novel was epic in scope — spanning time, space, and multiple civilizations, and describing how Earth would deal with the possible end of humanity. “This was what Chinese science fiction was lacking: a grand narrative,” Yao told Sixth Tone in a phone interview.

During the “Golden Age” from 1979 to 1983, lax rules on culture following the Cultural Revolution saw a number of excellent sci-fi magazines and writers blossom. But the promising spring of sci-fi was fleeting. In 1983, a debate raged between book critics over the very nature of science fiction: Should it try to popularize scientific knowledge, or focus on creative writing? Ultimately, an editorial in Party mouthpiece People’s Daily later that year gave the final verdict: Sci-fi was spiritual pollution. The once-flourishing scene went dormant, and nearly all publication of magazines and books ground to a halt.

By 1997, the genre was picking up steam again. That year, Beijing hosted the International Conference on Science Fiction, ushering in a renewed excitement for Chinese sci-fi. In 1998, Yao started working at Science Fiction World magazine in Chengdu, the capital of China’s southwestern Sichuan province. The next year, Liu — then an engineer at a power station in northern Shanxi province — got four of his contributions published in Science Fiction World. In 2002, Yao became responsible for editing Liu’s submissions.

The editors and Liu opted to serialize “The Three-Body Problem” in Science Fiction World, which at the time had a 200,000 nationwide circulation. They were worried that Chinese readers wouldn’t be especially interested in sci-fi compared to other literature genres, but hoped that “The Three-Body Problem” could open up a new chapter for Chinese sci-fi.

And it did — for a time.

In 2015, the first installment of “The Three-Body Problem” trilogy won the prestigious Hugo Award for best novel, triggering media coverage and large-scale public attention — including, famously, an endorsement by former U.S. President Barack Obama. It increased the profile of Chinese sci-fi both domestically and internationally, and raised the possibility that sci-fi could finally extend beyond the pages of novels. In 2014, after the English-language translation was published, Chinese movie production house Yoozoo Pictures announced that it would adapt the series into a six-part motion picture.

But the much-hyped movie never happened. Filming took place in the first half of 2015, and the first movie was scheduled to premiere in July 2016. Over the past three years, the schedule has been continuously pushed back, in part due to sky-high expectations for visual effects and an unexpected company restructure.

There’s been no news recent news about “The Three-Body Problem” movie, but after a report in March that Amazon’s on-demand service planned to create a television show of the series, Yoozoo reiterated that it was the franchise’s legal copyright holder for all types of adaption. At a group interview with Sixth Tone and other media outlets during the anniversary meeting, Liu — who is serving as the project’s chief consultant — directed all questions about the movies to Yoozoo. For now, “The Three-Body Problem” remains hamstrung by its lack of visual depictions; it can hardly monetize certain aspects of the stories like international franchise “Star Wars” has been able to do with lightsabers if there are no movie or game representations.

The market for China-made sci-fi remains untested, but the success of sci-fi blockbusters in China suggests that Yoozoo could be sitting on a possibly untapped goldmine. In 2010, James Cameron’s sci-fi epic “Avatar” became the first-ever movie to take in over 1 billion yuan (roughly $150 million) in China’s box office. A number of Chinese sci-fi movies are underway, including an adaption of Liu’s novella “The Wandering Earth,” and “Shanghai Fortress,” starring Lu Han who’s been dubbed China’s Justin Bieber.

Nevertheless, there’s one high-profile “Three-Body” adaption that’s definitely still happening. Youzu Interactive, a gaming giant which shares a founder with Yoozoo, recently revealed that in 2016, it had signed an animated depiction of the series created by an enthusiastic fan. Li Zhenyi, now aged 29, began animating “The Three-Body Problem” series in 2014 when he was a university student in France. Back then, it was a solo passion project using “Minecraft” — a sandbox game that allows players to create anything using digital blocks. His project was never intended to become what it is now: a two-season series with over ten million total views, mostly on streaming site Bilibili.

“I like ‘Three-Body’ because it’s beautiful,” said Li, who became hooked on sci-fi in high school after stumbling upon a copy of Science Fiction World magazine on a janitor’s desk. Back then, he tried to persuade his fellow students to read it, but they were more drawn to books with colorful illustrations and simple storylines. Motivated by introducing more people to the series, he began animating it, believing that the series’ complex descriptions of science and technology might be hard for average readers to understand. “After we visualize [the series], it will become much more popular — after all, human beings are visual animals,” he said. “If we stick steadfast to the books, they’ll only reach a few people.”

Li’s first attempt was fairly poor — hardly surprising, given his amateur skills. It was not until the fourth episode that he had a team helping him animate and produce the episodes, and it wasn’t until the ninth that they began using a more professional drawing tool. In 2016, the self-financed project almost ended, as the enormous workload and prolonged production time pushed Li and his team to the edge. But when Li found himself a backer in Youzu, he quit university and moved to Shanghai. He has no plans to graduate — he’s already doing his dream job.

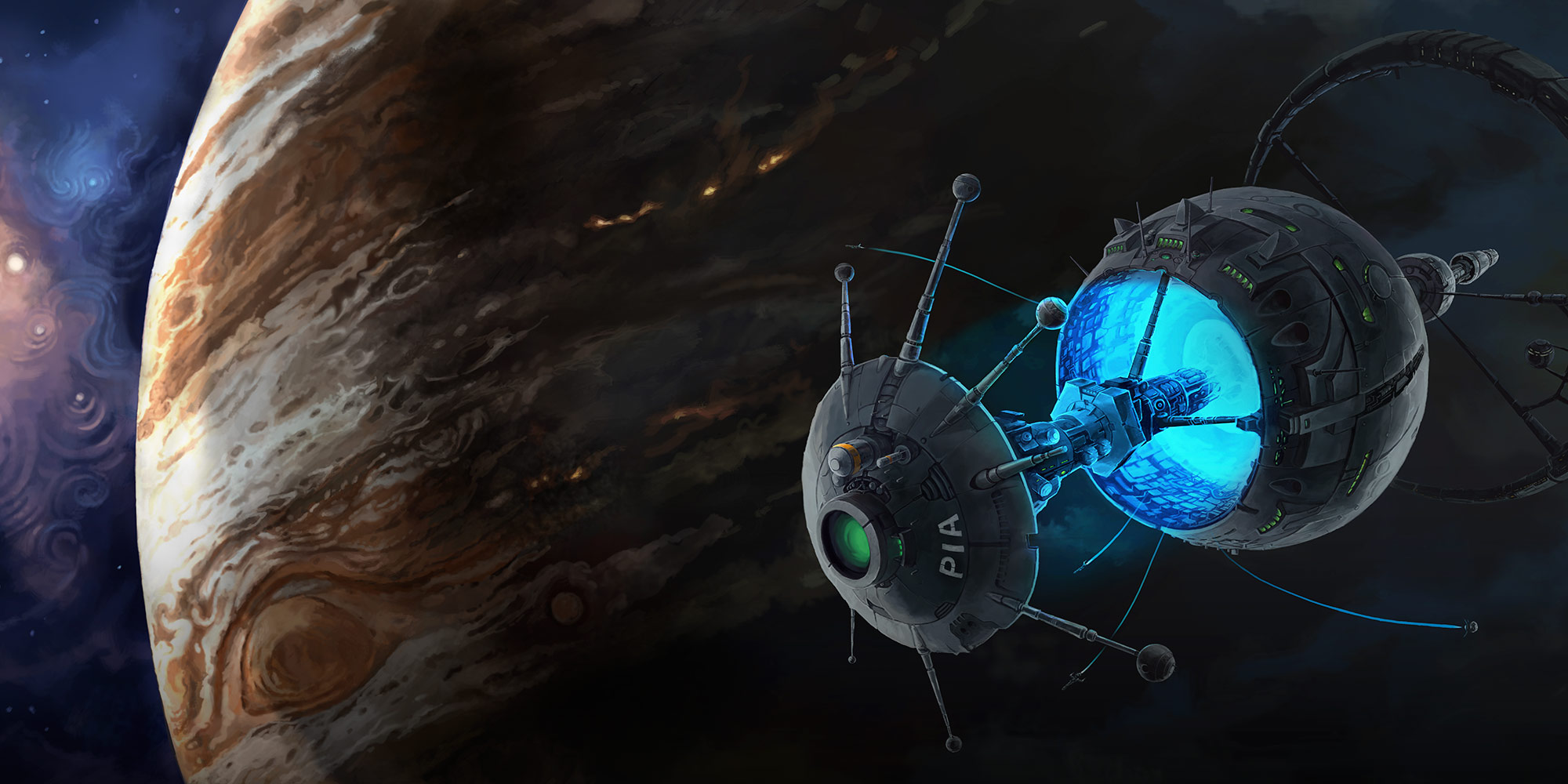

Episode 11 of ‘Legend of Luoji,’ the second season of ‘The Three-Body Problem’ animated series.

As someone with firsthand experience leveling up “Three-Body” projects, Li agreed with Liu’s oft-stated opinion that people should be more patient about the long wait for the film. “Sci-fi movies have just started to be made in China, so they’re taking baby steps,” said Li, “You can’t expect [sci-fi movies] to reach the sky in only one leap.”

Beijing-based startup Future Affairs Administration (FAA) is one group trying to give Chinese sci-fi a boost — it wants to cultivate more writers and connect them with commercial institutions. Established in 2016, FAA organized the event that brought Liu and ETO members together in May. “Before 2015, China’s science fiction had no business model or commercial potential,” Li Zhaoxin, co-founder of FAA, told Sixth Tone. “It’s fair to say that China basically didn’t have people working on science fiction full-time four or five years ago.”

China has at most 100 sci-fi writers who are able to write a book a year, while the United States has over 1,000 people registered with Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Li Zhaoxin said. “Without quantity, it is unrealistic to pursue quality,” he added. For the few writers who are still penning stories, the dwindling publishing industry makes it increasingly hard for them to survive by writing alone. The key, in Li Zhaoxin’s opinion, is to give aspiring creators hope that they can actually earn money from their talents, rather than writing in their spare time on top of other full-time jobs.

One of the major ways to reap rewards from books is to sell the intellectual property. Currently, FAA has six projects in negotiation — they've also begun working on a “Three-Body Cosmos” spinoff, which will feature a number of projects including a comic book. “The problem we are facing now is how to get film and television to match the pace of sci-fi,” Li Zhaoxin said. “This isn’t just a problem with science fiction — the whole movie industry still needs quite some time.”

Both Chinese sci-fi newcomer Li Zhaoxin and veteran editor Yao agree that traditional publishing will no longer be at the core of future science fiction. Yao knows that the book that he once spent countless hours pondering over has dramatically changed Chinese sci-fi. “Sci-fi no longer belongs to the genre of literature,” he said.

With only eight years until he reaches retirement age, Yao sometimes wonders how much he can still contribute to China’s science fiction — the one thing he holds dear. When it comes to “The Three-Body Problem,” he has complicated feelings. “On the one hand, I want it to become a classic that every generation of readers can fall in love with,” said Yao, “On the other hand, it will not be a good thing if it’s still the only sci-fi book we’re talking about in 10 years.”

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: ‘Three-Body — The Bunker City’ by Jin Linhui, May 2017. Courtesy of Future Affairs Administration)