Unmuzzled Guide Dog Turned Away by Beijing Subway

A golden retriever was recently turned away by Beijing subway staff for not being properly muzzled, leading her visually impaired owner to criticize the transport authority’s unsympathetic regulations and again casting a spotlight on China’s spotty treatment of people with disabilities.

The owner, 37-year-old Xu Jian, was stopped by subway employees at Jintaixizhao Station on Line 10, along with her guide dog, Daimeng, on Nov. 3. Despite checking Xu’s disability certificate to verify that she was indeed visually impaired, the security staff turned her away because her dog was not wearing a muzzle, which they argued might cause passengers to feel uncomfortable or frightened.

The dispute lasted more than six hours, until the subway closed at midnight. After demanding an apology, Xu and her husband were escorted to a private room, where they remained for several hours. Eventually, they were promised a written apology from lower-level staff, though the station head did not end up approving this request.

Xu described the police officers who arrived at the scene as rude and intimidating. “I was scared,” she told Sixth Tone. “Daimeng was trembling — she was scared, too.”

Animals have long been banned on China’s public transportation because of the public safety risks they can present. Guide dogs, however, became an exception in Beijing after a new regulation took effect in May 2015. The regulation states that when visually impaired people take public transport in the capital, they should bring their disability certificate, harness, and service animal certificate — all of which Xu had — as well as “protective equipment” for their dog to prevent it from posing a danger to others.

The regulation does not specifically mention muzzles as a requirement for guide dogs. Moreover, Xu said that wearing a muzzle could impede a guide dog in performing its duties.

“If the dog is muzzled, it can’t focus on its work,” she explained. “It is essential to revise [the regulation] because it is not suitable for practical situations, for using guide dogs in daily life.”

Liang Jia, a staff member at the China Guide Dog Training Center in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, where Daimeng was trained, explained the physiological importance of a dog being unmuzzled. “Dogs pant with their mouths open to cool off,” she told Sixth Tone. “If they’re feeling hot and uncomfortable, they can hardly be expected to put their full attention toward serving their owners.” Liang believes that at present, Chinese society is “inadequate” in terms of accommodating guide dogs and their disabled owners.

Just the day before the subway incident, Zhou Yunpeng, a bling folk singer, was reportedly turned away from several hotels in Hangzhou, the capital of eastern China’s Zhejiang province, because he had a guide dog. A staff member from the Shanghai Guide Dog Association who declined to be named because she was not authorized to speak to media told Sixth Tone that at present, China has no uniform standard for guide dogs, let alone any overarching requirement that they be muzzled. “In some countries, special equipment is required — not for preventing the dog from hurting others, but for better directing the dog,” she said.

Such a national standard for guide dogs is actually being developed by the China Blind Person’s Association, but no timeline has been given for when it will be released.

The Beijing subway did not respond to Sixth Tone’s interview request. However, it told Beijing Youth Daily that the staff members involved in the incident had handled the situation according to official regulations and were merely considering the safety and comfort of other passengers.

Xu, however, sees serious flaws in this logic. “A guide dog would never hurt anyone — there’s no record that this has happened before,” she said. Rather than just taking into account the interests of the general public, she added, the subway staff should try putting themselves in the shoes of traditionally marginalized communities like the blind.

Guide dogs are in short supply in China, with only around 130 in service, according to Liang. After a year of waiting, Xu was finally able to adopt Daimeng in January of this year. “Having a guide dog has changed the course of my life,” she said. “It saves time for my family, for volunteers. I can now spend time going places on my own. And when Daimeng is with me, I feel safer. This is about personal dignity, about visually impaired people being able to get around independently.”

“I hope the [revised] regulation will be more comprehensive, more thorough, and more humane,” Xu said.

Editor: David Paulk.

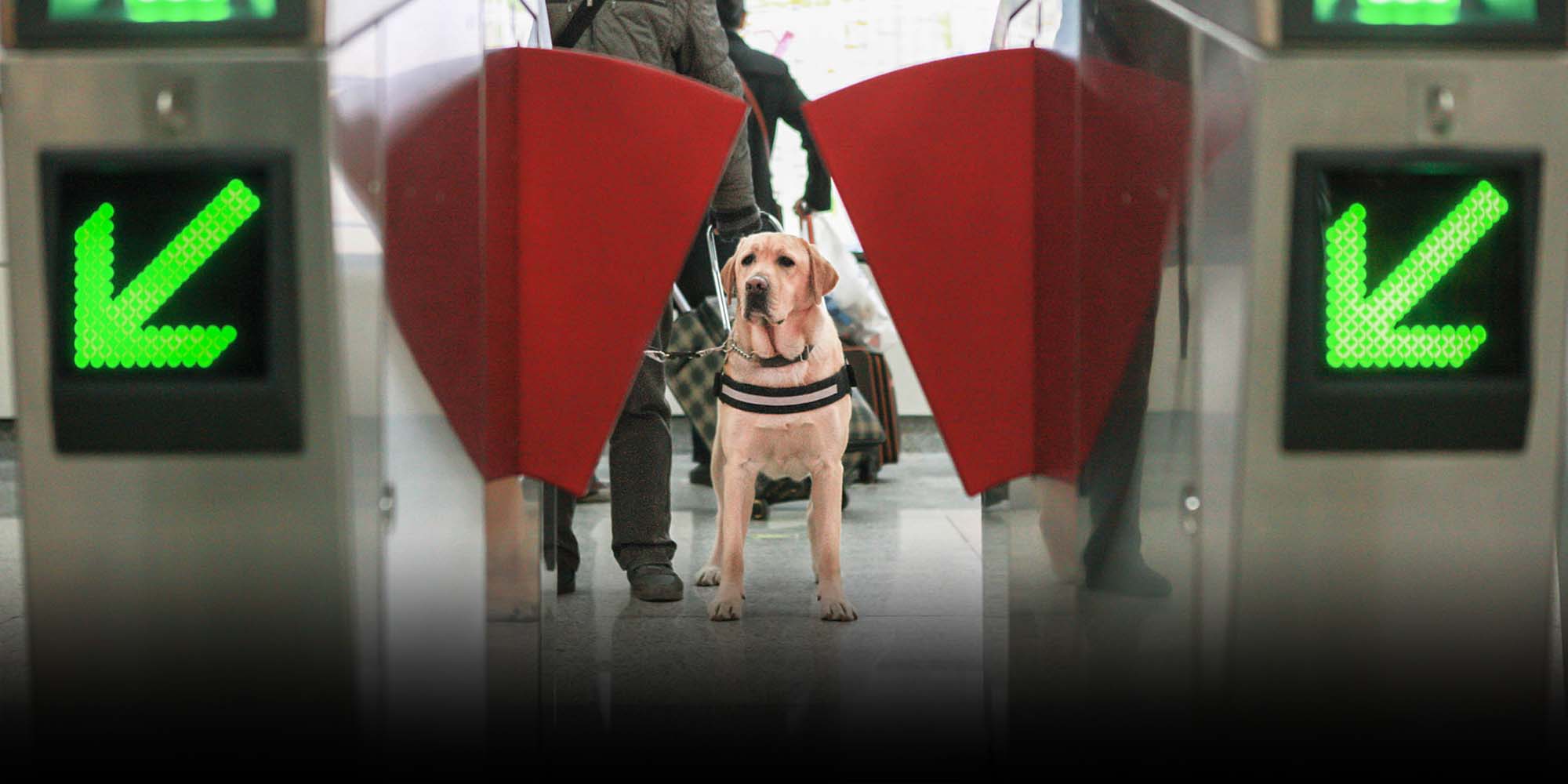

(Header image: A visually impaired man waits to pass through an electronic turnstile with his guide dog at a subway station in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, Nov. 27, 2012. Zhang Di/VCG)