How Many Parks Make a City?

Editor’s note: Forest parks, People’s Parks, historic French parks, formal Chinese gardens, downtown pocket parks ... Shanghai’s 532 parks make up the most extensive system of public space of any Chinese city. In this series, Sixth Tone explores how people relate to green space in the megacity.

In 2020, Shanghai announced an ambitious plan to more than double its number of city parks. Dubbed the “Thousand Parks Project,” the city expects to have over 1,000 parks by 2025, including everything from large-scale urban greens and riverside walkways to 300 pocket parks, 200 rural parks, and 50 forest parks on the city’s outskirts. All this is in service of the goal, by 2030, of becoming a “park city.”

These are not trifling numbers. When the building program was launched in 2020, Shanghai had only 406 parks citywide, and the pandemic has not made construction easier. But officials see the plan as crucial to ameliorating some of the problems associated with Shanghai’s breakneck development over the past 30 years and keeping living standards competitive with resurgent nearby cities like Suzhou or the tech hub of Hangzhou. Yet, while the benefits of park construction may be obvious, the current prioritization of raw acreage over accessibility, ease of use, and integration into communities may not produce the intended improvement to residents’ lives.

Although Shanghai was the first city in the Chinese mainland to build a modern, Western-style public park, 20th century urban planning decisions combined with the recent construction boom have left its overall park space lagging far behind even smaller cities. Public green space area in Shanghai is only 8.5 square meters per capita, barely half the 15.5 square meters in Hangzhou, and that’s including a number of large — and largely inaccessible — parks far from the urban core. Even many of the city’s new luxury residential areas have no central community park and are located far from the nearest city park.

Shanghai has never had a green corridor, or broad park path, stretching across the city like Central Park in New York. There are historical reasons for this. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Shanghai was divided into different concession areas, which were managed and planned separately, and thus never produced a complete or coherent urban green space system. After 1949, although a preliminary green space blueprint was made along Soviet lines, the urban core’s high density of residential and commercial buildings left little room for park construction.

From 1949 to the 1980s, newly built worker communities set aside space for recreation, but there were few comprehensive parks, and maintenance was spotty. Residents could only exercise in the narrow strips inside their community compounds, on the edge of urban roads, or at the entrances to public buildings — all of which caused conflict with neighbors, businesses, and passersby. Although each district has at least one or two large comprehensive parks, their number is small and their radius large, limiting their utility to all but the nearest communities.

After the Cultural Revolution, when parks were destroyed or closed as symbols of bourgeois life, China’s “reform and opening-up” policy ushered in a surge of park construction. Especially in the 1990s, new parks sprouted up all over Shanghai. To meet the standards of a “national garden city” — a useful résumé burnisher for ambitious officials — Shanghai planners designated new parks on the then-outskirts and cleared room next to the main roads and rivers downtown. The peak of the park boom came in the run-up to the 2010 World Expo, as the city renovated its old parks, such as Renaissance Park (the former French Park), and Lu Xun Park (the former Hongkou Park). Some of the Expo’s key exhibition areas were themselves later turned into parks, including the recently completed World Expo Cultural Park.

Nevertheless, after the tide of visitors from the Expo dissipated, new urban park construction shifted. Planners’ focus returned to the suburban periphery and downtown waterfronts, including 21 suburban parks stretched across 400 square kilometers of farmland, forest, and villages. Downtown, new belt parks and walking paths were built on the site of relocated industrial plants. In the five years from 2015 to 2020, the number of parks in Shanghai almost tripled, from 165 to 406.

Yet this construction spree did not significantly increase the number of parks accessible to the majority of Shanghai residents in their daily lives. The emphasis has been on size — increasing per capita green space for statistical purposes — rather than distribution, so the experience and utilization of these parks by ordinary residents has not significantly improved.

These issues can be seen in a place like Century Park in the city’s Pudong New Area. As urban housing and land prices have risen over the past 20 years, community parks have shrunk to make room for housing, and more emphasis has instead been placed on centralized large parks like Century Park to pick up the slack. But while the original intention was to build parks big enough to serve a wider swath of residents, a lack of exits and entrances means accessibility is less than ideal. Meanwhile, the park has exacerbated land and housing price increases nearby, as residents compete for precious green space.

Not all parks have struggled to realize their ambitions. Renovation projects have achieved good results by better integrating older parks into surrounding neighborhoods. The Golden City Road project in the Gubei neighborhood west of the city center, for example, utilizes a wide green belt to link external parks into nearby communities, and has greatly enhanced the accessibility of park space in the area.

The city’s downtown remains a sore spot. The transformation of old parks can positively impact surrounding areas, but the construction of large central parks has not produced the expected results. The continued lack of small and medium-sized parks, especially community parks, has led to an uneven and occasionally unfair distribution of green space.

Therefore, the goal of the Thousand Parks Project should be to improve the overall accessibility and utility of Shanghai’s parks, rather than actually building a thousand parks. The key guiding concept here shouldn’t be the construction of a “park city,” but a “people’s city.” This involves more than just park construction, but also improving park governance. Where will the land come from? How can isolated parks be linked into a broader network of green spaces? And how to balance the different needs of young people, families with children, and the city’s rapidly ballooning elderly population?

It is no simple task to double the number of a city’s parks in five years, but the real challenge — the one that counts — is creating high-quality parks that serve city residents of different classes and locations without cutting corners. The Thousand Parks Project will likely achieve its goals, but we shouldn’t overlook the difficulties and compromises involved. A megacity like Shanghai needs not just large landmark parks, but also specialized and community parks, street greenery, and pocket play areas. These spaces must serve the health of the elderly, while not alienating young people. They must offer room for residents to socialize, for parent-child activities, and for relaxation and conversation between work hours.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

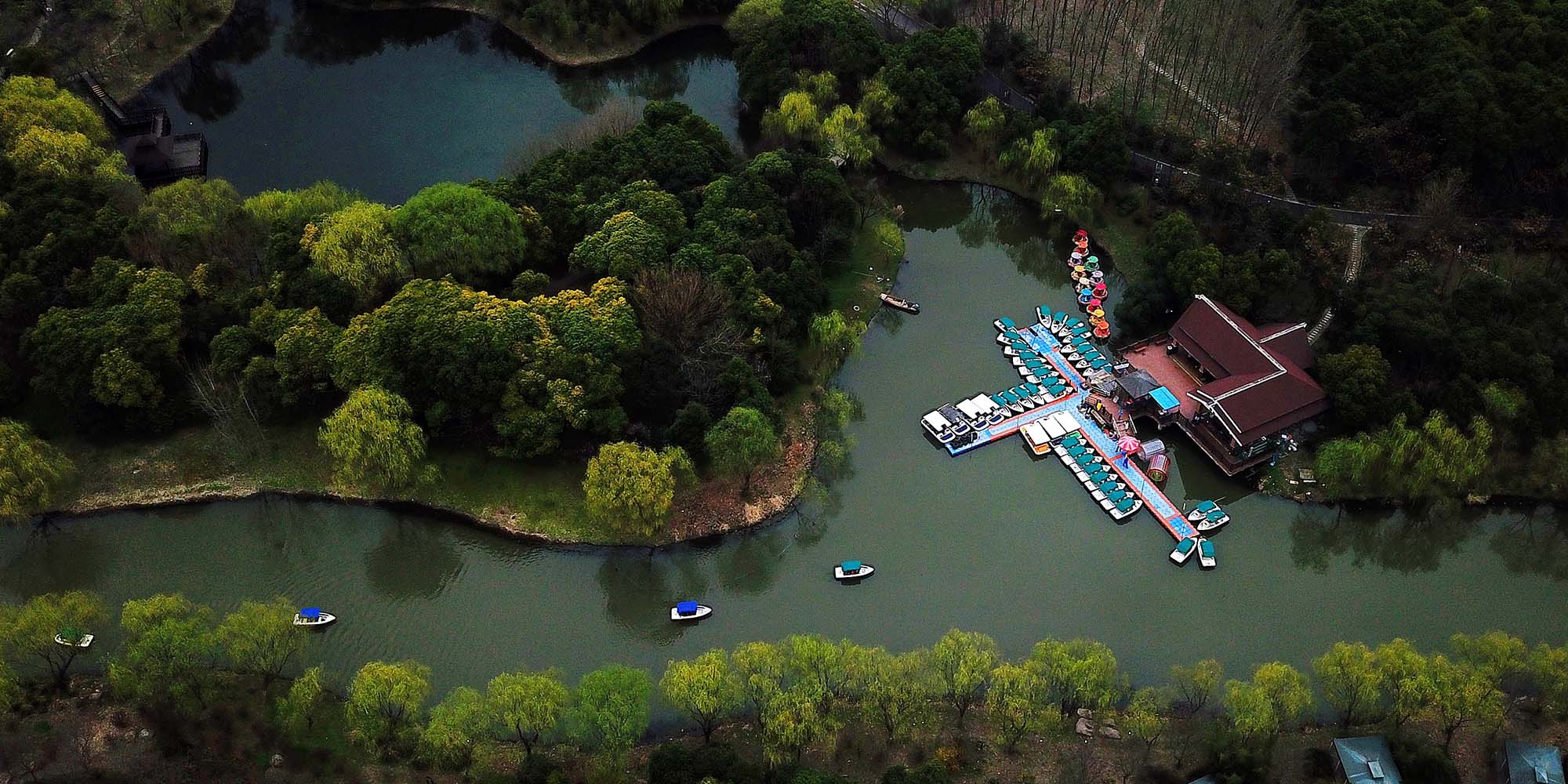

(Header image: A view of Gucun Park in Shanghai, March 14, 2018, VCG)

Click here to read more.