How Ping-Pong Turned the Tables of the Cold War

Fifty years ago today, the U.S. lifted its 21-year trade embargo on China.

The relaxation of American trade restrictions was a milestone in the restoration of U.S.-China relations during the Cold War. Ultimately, it also helped pave the way for China’s growth into a global power.

But for many, the moment that set the ball rolling toward a rapprochement had actually occurred two months earlier in an unlikely setting: a table tennis tournament in Japan. Or more specifically, on the Chinese team’s bus.

It was here that a fateful encounter occurred between two young ping-pong players — the American Glenn Cowan and the Chinese team captain, Zhuang Zedong — that helped break the ice between the two Cold War powers.

Cowan, who had wandered on to the wrong bus, ended up chatting with Zhuang during the short ride to the competition venue. When the pair got off the shuttle together a few minutes later, they caused a media sensation.

“It really was just a matter of chance,” Xu Yinsheng, who coached the Chinese team at the tournament, told Sixth Tone at a press event in April. “Zhuang Zedong did the right thing in the right place, and at the right moment.”

Half a century later, it’s difficult to grasp the impact this simple gesture of goodwill had on both sides of the “Bamboo Curtain.”

By 1971, the United States and China had not had any official contact since the Communist Party of China came to power in 1949. Just 18 years previously, the two countries had been fighting a bitter war in Korea.

Leadership in both countries had recently opened to a thaw in relations. China hoped a closer relationship with America would help counter the threat from its former ally, the Soviet Union. U.S. President Richard Nixon, meanwhile, aimed to exacerbate the divide between the two communist powers by leaning toward China.

But the political realities of the Cold War made any rapprochement a hard sell for both governments. In the U.S., anti-communist sentiment remained high. American citizens were banned from traveling to China — and risked having their passports revoked if they did so.

China was four years into the Cultural Revolution, an anarchic decade of internal strife during which those deemed enemies of communism — including colluders with foreign powers like the U.S. — were brutally persecuted by their fellow citizens. The upheaval was even felt inside the nation’s sports teams, with many formerly idolized athletes suddenly reviled and persecuted as “revisionists.”

Xu, the coach, recalled Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai asking the Chinese ping-pong team to discuss among themselves whether to attend the World Table Tennis Championships in 1967. Xu was in favor, but a radical faction was fiercely opposed.

“They said the championship’s seven trophies were donated by the capitalist class, so if we participated, it would amount to pandering to them,” said Xu. “After an intense discussion, the premier assessed the situation … and finally decided that we wouldn’t take part.”

China also missed the 1969 championships for similar reasons.

But ahead of the 31st edition of the competition in March 1971, the Japan Table Tennis Association president, Goto Koji, was keen to have the Chinese team join. He sent an envoy to China to smooth the process, agreeing to a wide range of demands — including the exclusion of the Taiwan-based Republic of China from the championships.

The event drew the attention of Chairman Mao Zedong, who felt it could be politically useful, said Xu. After another team discussion initiated by Zhou, the Chinese leadership decided the Chinese players should attend.

“The team should go,” ordered Mao on March 15, “and should fear neither hardship nor death.”

Before the competition began, Zhou briefed the team at length on the greater purpose of their mission, said Xu.

“The premier constantly reminded us that we were going out not just to compete, but to make friends,” said Xu. “He said the main thing was to further the peace of humanity. … We felt this instruction was very novel at the time.”

The tournament finally got underway in Nagoya, Japan, on March 28, 1971. China soon returned to its habitual supremacy on the ping-pong table, winning four gold medals and three silver medals in the seven events.

The Chinese team stayed in their own bubble throughout. They had their own bus, hotel, training area, and even their own chefs. Meaningful contact with foreign players beyond competition and courteous post-match handshakes seemed unlikely.

But then, on one of the last days of the competition, Cowan — a self-professed hippie with a large bob of thick hair — got on the Chinese team’s bus as it was waiting to depart from the training ground.

Xu, the coach, was sitting on the bus at the time. He said he decided to ignore Cowan, as it seemed like an ordinary mistake. But Zhuang Zedong, a three-time world champion, didn’t feel it was right to leave the American sitting all by himself.

In later interviews, Zhuang described how he hesitated for 10 minutes before going over to Cowan. “Imperialist America” had long been China’s No. 1 enemy, and a friendly gesture could be construed as collusion. But in the end, he decided to heed Zhou’s advice to exhibit the spirit of “friendship first.”

With just five minutes of the ride left, Zhuang made his move. Rummaging through his bag for potential gifts, he grabbed a silk embroidery of a Chinese landscape. Ignoring his teammates’ repeated objections, he walked down the aisle and sat next to Cowan.

Zhuang shook the teenager’s hand, presented the gift, and chatted with him through an interpreter for the next few minutes.

When they arrived at the venue, the waiting journalists were surprised to see a Chinese and American athlete hop off the bus together. A photo of the pair shaking hands made the front page of newspapers all over Japan the next day. Before long, it had spread to media the world over.

A day later, Cowan surprised Zhuang with a gift of his own: A T-shirt emblazoned with the peace logo in red, white, and blue, and the words “Let It Be” — from The Beatles song — below it.

At the time, ping-pong teams from Australia, Canada, Colombia, Nigeria, and the United Kingdom had been invited to visit China. Days before, the president of the United States Table Tennis Association had teasingly asked why they had been excluded from the trip.

But in the context of the recent gesture of friendship between Cowan and Zhuang, the question ended up sparking furious discussion among the Chinese leadership. Finally, Mao decided to officially invite the Americans over for a historic visit on April 6. Nixon also authorized the U.S. team to go.

“We later heard that China had invited America to visit, and we felt very shocked. What was going on?” recalled Xu. “We knew this was definitely a big deal.”

On April 10, a curious group of table tennis players — including Cowan in his flared trousers — crossed into mainland China from Hong Kong. They spent the next 10 days on a whirlwind tour of Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin, dining at state banquets and visiting sites including the Great Wall, some Ming dynasty tombs, and a steel refinery.

The U.S. team also played a series of exhibition matches in packed arenas. They lost most matches, though their hosts allowed them to win the occasional game out of courtesy.

Participants remember being swarmed by curious locals wherever they went. In turn, they got a glimpse of a China that has long since vanished: crowds of workers in gray-blue overalls, walls plastered in political slogans, and portraits of Chairman Mao hanging everywhere. One even spotted a sign with the English words “down with the Americans and their running dogs” that had been hastily covered over with the slogan “Welcome American Team.”

There were small mishaps along the way. Wandering Beijing in the early hours, Cowan saw a bike and decided to ride it, reasoning that in communist China all property was shared. But when an angry crowd surrounded him, he quickly realized he’d been mistaken, and fled back to his hotel.

The trip accelerated the normalization of U.S.-China relations. Even while the team was in China, Nixon announced that America would relax restrictions on Chinese visitors and currency flows, and allow U.S. oil companies to provide fuel to Chinese merchant ships. In June, the trade policy change came into force.

The month after that, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger made a secret trip to Beijing. This paved the way for Nixon’s surprise visit to China in February 1972, which the U.S. president later dubbed “the week that changed the world.”

During his meeting with Nixon, Mao famously commented that “the little ball moved the big ball,” referring to the ping-pong matches’ global impact. Nixon later remarked that the Chinese leaders appeared to be almost as pleased with the way the meeting had come about — that is to say, through table tennis — as they were with the event itself.

There’s still debate over the extent to which China’s ping-pong diplomacy was a happy accident, or a masterfully planned act of statecraft. In a 2014 book, journalist Nicholas Griffin argued that key details — such as Cowan purportedly being waved on to the Chinese bus, and the Chinese team selecting a gift carefully in advance — tend to be left out of accounts of the incident in both China and abroad.

But few dispute the importance of ping-pong diplomacy in restoring U.S.-China ties. Griffin said the exchanges helped humanize China in the eyes of foreign nations. Xu agreed they helped set China on a new course.

“Ping-pong diplomacy drove the change to a new world order,” said Xu. “China benefitted from it. … It was good for its ‘reform and opening-up.’”

Xu still maintained that Cowan and Zhuang’s original encounter happened purely by chance, but candidly admitted a different event — such as a basketball game — could have helped break the ice instead.

“The leaders on both sides were thinking about how to change the situation,” said Xu. “It wasn’t possible that China and America would not talk to each other forever.”

With this year’s Olympic Games set to be held in Japan, and U.S.-China relations at a low ebb, the 50th anniversary appears to hold added significance. Commentators in both America and China have been looking back on ping-pong diplomacy in recent months, asking whether the events of 1971 still hold lessons for the world today.

China’s table tennis team are due to depart for Tokyo in just a few weeks. Xu expects the players to give their all, but also hopes they’ll keep in mind the higher goal he was taught 50 years ago.

“They should make a contribution to world peace, even if it’s a miniscule one,” said Xu. “You always need to look a bit further, at the bigger picture.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

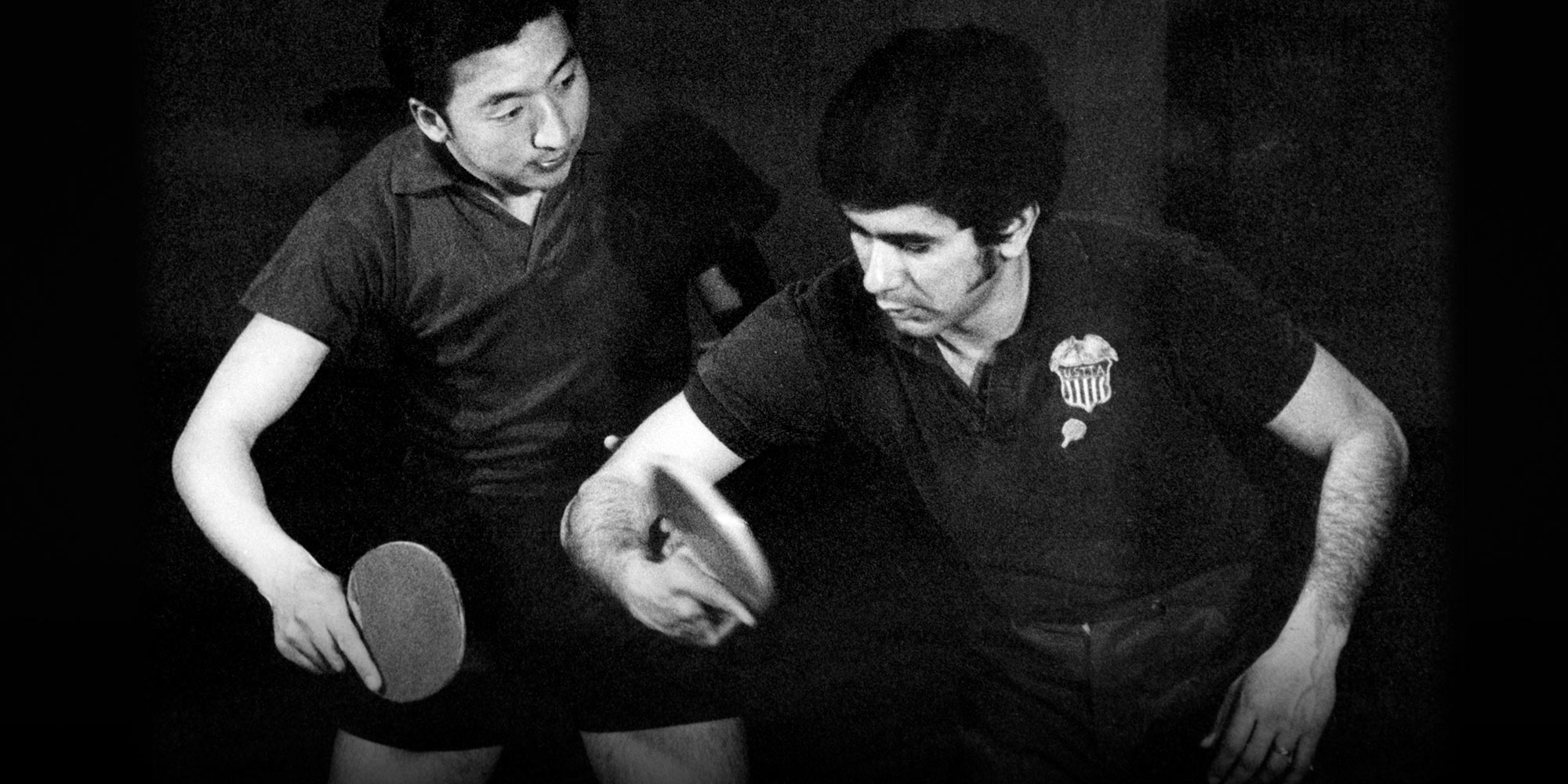

(Header image: An American tennis table player (right) trains with a Chinese player, in Beijing, April 1971. AFP/People Visual)