Why China’s Students Are Being Told to Kneel Down and Take a Bow

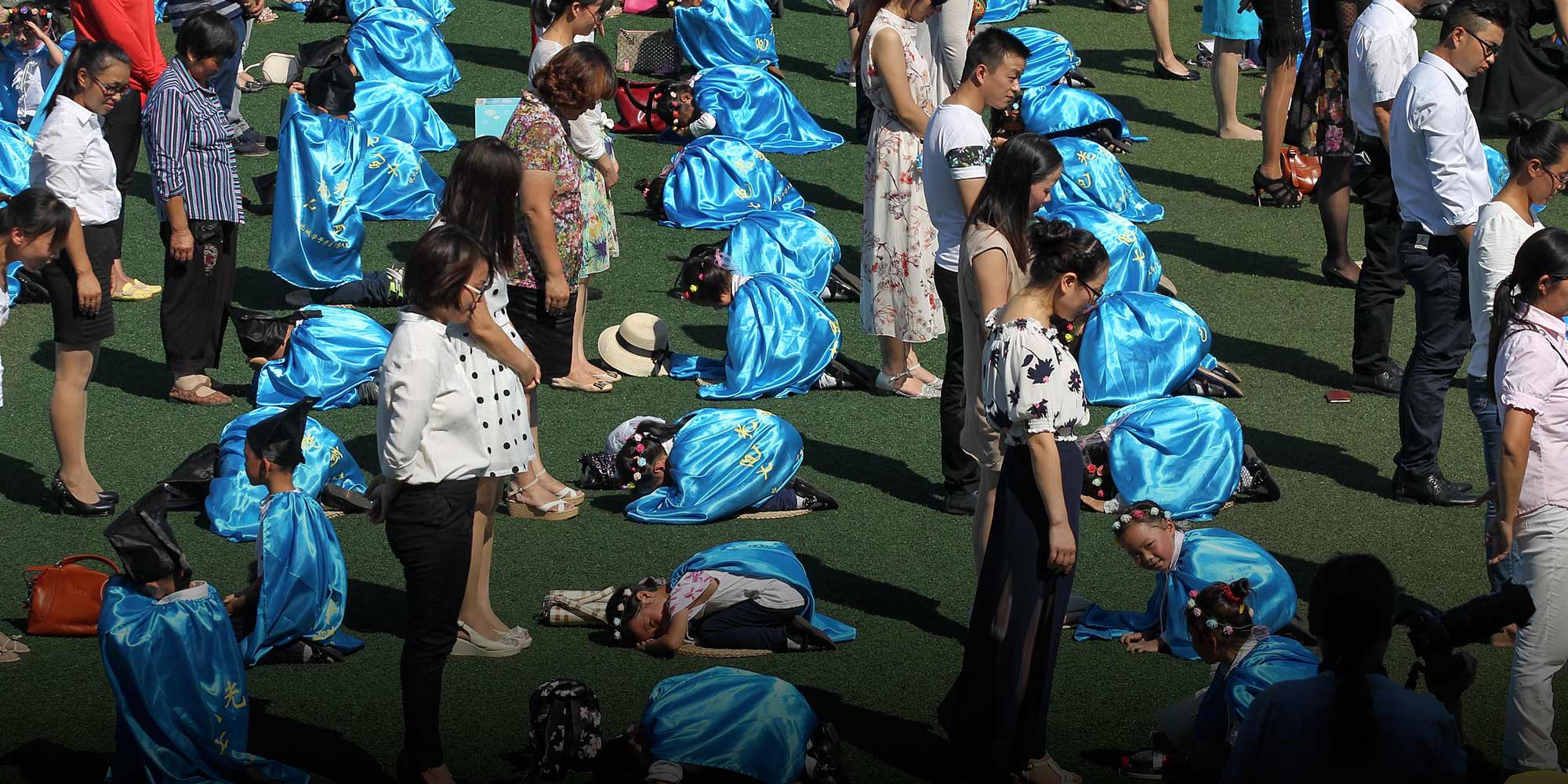

In recent years, there has been an uptick in reports of Chinese students being required by their schools to kowtow — do deep bows in which their heads touch the ground — before their parents. Two months ago, nearly 2,800 high schoolers in the central province of Henan were made to kowtow to their parents in a mass ceremony. Last January, a viral video from the eastern province of Shandong showed a tearful woman — a member of a local nonprofit — ordering about 100 students to kowtow to their parents. When reporters contacted the school’s principal for comment, he defended the event and called kowtowing to one’s parents a “good Chinese tradition.”

While many Chinese have expressed revulsion at the reemergence of what they consider a regrettable aspect of China’s hidebound feudal past, their anger is misplaced. Kowtowing is not merely some outmoded relic: It has been part of traditional Chinese culture for millennia. The problem isn’t the act itself; it’s that school administrators are forcing students to kowtow. In doing so, they betray a fundamental misunderstanding of both the ritual’s true meaning and their own role as educators.

To kowtow is to show obeisance: It’s a symbol of your utter and complete respect and gratitude for the other party. In traditional Chinese culture, there’s no conception of a personalized god who goes around issuing commandments, punishing evil, and rewarding good behavior. Instead, Chinese worshipped at the altars of a wide variety of different deities, depending on the needs of the moment. Among the most widely recognized and frequently invoked spirits were a family’s ancestors — a faith known as ancestor worship.

Confucianism enshrined this practice and laid out a set of widely recognized rituals for governing it. And although the Confucian tradition lionized “men with gold under their knees” — fiercely independent types who refused to sacrifice their pride and kowtow before authority without just cause — exceptions were made for one’s parents and forebears. The influential neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi made kowtowing to one’s parents and ancestral shrine a necessary component of just about every ritual ceremony — from weddings to funerals.

Over time, kowtowing became a part of daily life. In Nishan, near the birthplace of Confucius in the eastern province of Shandong, a 90-year-old woman once told me that, when she was a child, she was made to kowtow to her parents before going to visit her relatives during Spring Festival, and then again, when she returned with these same relatives’ best wishes.

There is a lot in traditional Chinese culture that should be left in the past — footbinding, for example — but there are relatively few negative things to be said about the rites of filial piety. Our parents sacrifice a lot for us. If anything, kowtowing before them fulfills a deep-rooted spiritual need to show gratitude and repay their kindness. It’s an expression of human nature.

Not everyone agrees, however. The New Culture Movement, which began shortly after the collapse of China’s last imperial dynasty in 1912, sought to eliminate the rites of filial piety, including the act of kowtowing to one’s parents. Half a century later, during the bloody years of the Cultural Revolution, kowtowing was labeled one of the “dregs of feudalism,” and the country’s children were instead incited to betray and report on their own parents — an act that violates the most basic tenets of civilization.

At their root, these campaigns were grounded in an ideological misunderstanding: that traditional ethics and morality are incompatible with democracy and freedom. This confuses human relations with politics. Democracy and freedom are political rights; filial piety is a matter of ethics and familial rites. If you think that kowtowing to your elderly mother violates your human rights or your freedom, that only proves you aren’t able to distinguish politics from ethics. This fundamental confusion, however, has led many modern Chinese intellectuals astray, especially radical intellectuals.

Filial piety and showing respect for your parents is not something we should be trying to discourage. The rapid pace of China’s modernization drive has greatly strained the country’s family structures — especially in rural China — and the news is seemingly filled with stories of children abandoning, abusing, and even attacking their parents. In 2014, an officially backed sociological study on suicides within the elderly community in the Chinese countryside concluded that the problem was due in large part to a lack of support for dealing with financial and health problems, as well as feelings of loneliness.

Teachers and principals are well-positioned to encourage children to rethink their relationships with their parents, but judging by the above-mentioned cases, many are ill-equipped for the task. Some school leaders seem to have no idea what ritual acts like kowtowing truly mean.

Kowtowing before one’s parents is just one part of a broader set of familial rites. Confucianism — especially in its early days — makes a clear distinction between the public and private spheres. Whereas impartial justice must take precedence over emotion when governing a country, in families, the opposite is true. By the same token, the rituals of the home are not meant for public consumption. By ignoring this basic principle, schools muddle the distinction between different kinds of rites and turn family behavior into public behavior. This isn’t “rite.”

Familial rites must be based on true sentiment. A rite conducted spontaneously has a very different meaning from one ordained by administrative fiat. The “men with gold under their knees” idealized by Confucians might not have kowtowed before illegitimate authority, but they would be happy to do so before their parents. The task of a teacher should be to inspire students to act morally — not force them to do so. In the above-mentioned examples, the schools mostly stated that their goal was to teach students about traditional culture and gratitude. That all sounds very high-minded, but it’s not enough to have good motives: How the ritual is revived matters as well.

And ultimately, ignorance of the true tenets of Confucianism on the part of those trying to revive it may do more harm than good. Ironically, the greater their enthusiasm for the cause, the more damage they might do. It’s dangerous to devote oneself enthusiastically to ideas that one does not really understand. Such people tend to get caught up in the external trappings of a tradition and lose sight of its underlying meaning. They are merely playacting Confucianism, and in so doing, they are turning its rituals into something performative, rather than meaningful.

Reviving Confucianism doesn’t require a “movement,” and neither does kowtowing. Confucianism is a philosophy of life: It asks us to reflect on what is right and to act accordingly. It has no room for ostentatious displays of piety for piety’s sake.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Zhang Bo and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: Students kowtow before their parents at a primary school in Nantong, Jiangsu province, Sept. 10, 2015. Xu Congjun/VCG)