First Gene-Edited Babies Prompt Official Investigation in China

While a Chinese scientist claims to have produced the world’s first gene-edited babies in Shenzhen, the city’s medical ethics authorities say they hadn’t received an application to conduct such an experiment and are now investigating the case, according to officials cited by The Beijing News.

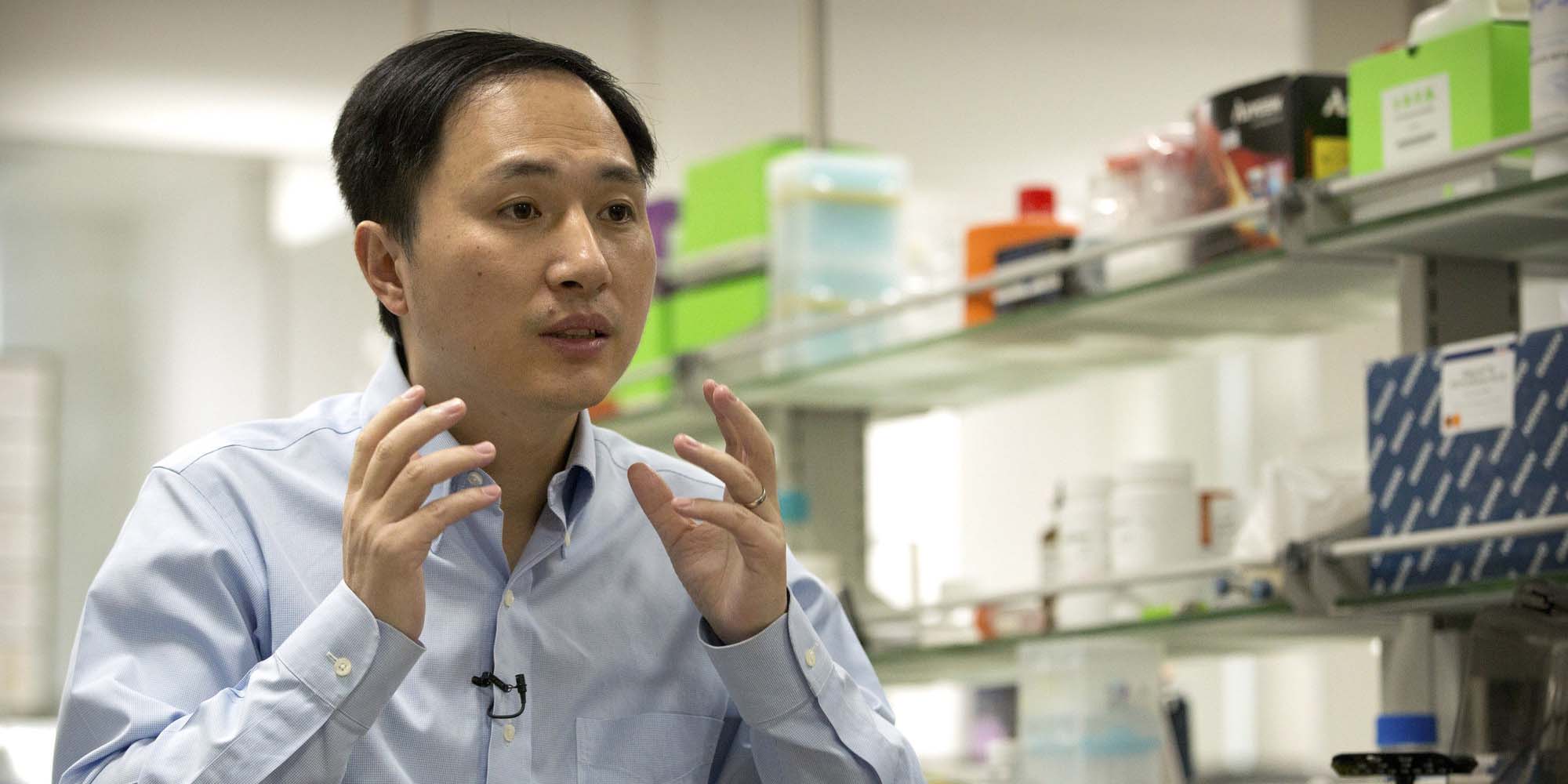

He Jiankui, an associate professor of biology at Southern University of Science and Technology and the experiment’s lead researcher, announced Monday that his team successfully managed to produce the first gene-edited children earlier this month in the southern province of Guangdong, according to The Associated Press. Only one pregnancy resulted from the project, though He altered embryos for seven couples in total during fertility treatments. The goal, he said in the interview, was to produce babies with the ability to resist HIV infection in the future by disabling CCR5, a gene that enables the virus to take hold.

A group of 122 Chinese scientists published a joint statement on Monday condemning the human experiment and calling for a legal investigation. He's university has also distanced itself from the experiment, claiming that it was not aware of it. “The biology department’s academic commission holds that he has severely violated our academic ethics and principles,” the university said.

He’s experiment has received both support and backlash from international academics. In the U.S., a gene-editing expert at the University of Pennsylvania told The Associated Press that it was “an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible,” while a Harvard University geneticist said the research is “justifiable.”

Zhang Linqi, a professor at Tsinghua University who specializes in HIV treatment, said that He’s gene-editing experiment using healthy embryos is “unwise and unethical.” “We haven’t found that Chinese people are able to go without the CCR5 [gene] entirely,” Zhang told iscientists, a well-known WeMedia account focusing on popular science. “The removal of CCR5 is not able to entirely prevent HIV infection due to the high variability of HIV.”

Chinese law stipulates that biomedical research on human diseases must first be reviewed by ethics authorities, according to guidelines from the National Population and Family Planning Commission implemented in December 2016.

With genomics becoming more widely discussed as a scientific and social topic in recent years, He’s gene-edited babies have ignited controversy on Chinese social media. By Monday evening, a hashtag on the experiment had received 420 million views on microblogging platform Weibo. “Ethics are shackles that humans put on themselves,” one Weibo user commented. “People are trying to replace God’s job,” another wrote.

Earlier this month, a public poll by Sun Yat-sen University revealed that while a majority of respondents in China supported gene editing and its legalization for treating diseases, they objected to gene editing for human enhancement. Last month, in another milestone, scientists in China successfully produced healthy mouse offspring from same-sex parents. Meanwhile, the country’s leading genomics company, BGI, is conducting China’s largest-ever genetic study to screen for birth defects.

He, who holds a Ph.D. from Rice University in Houston, will be a panelist at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong this week. He is scheduled to talk about human embryo editing on Wednesday and its “moral principles” on Thursday.

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

(Header image: He Jiankui speaks during an interview at a laboratory in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, Oct. 10, 2018. IC)