China’s Keyboard Cosplayers Take Fandom to the Text Level

With his permanent sneer and cold gaze, Severus Snape was rarely rattled. But as he watched his lover Lord Voldemort talking to Harry Potter, he felt his blood begin to boil.

“Who says I don’t understand love?” Voldemort whispered into Potter’s ear, as he leaned in to kiss him. Snape furiously confronted Voldemort: “We’re over.”

In her university dormitory, an upset Liu Liwen logged out and cast her phone aside. For a time, she sat in silence. She knew that it was all just a game, but that didn’t stop her from feeling genuine emotion. “I felt cheated on,” Liu recalls. “I was too naïve.”

For the past four years, 23-year-old Liu has been playing “chat cosplay.” By day, she works in southern Guangdong province’s city of Foshan as a financial manager at Ping An Bank, where she’s considered easygoing and patient by her clients and colleagues. But after working hours, she takes on one of her online alter egos: the cold and snide Snape from J.K. Rowling’s fantasy series “Harry Potter,” or the brooding, reluctant hero Jon Snow from TV drama “Game of Thrones.”

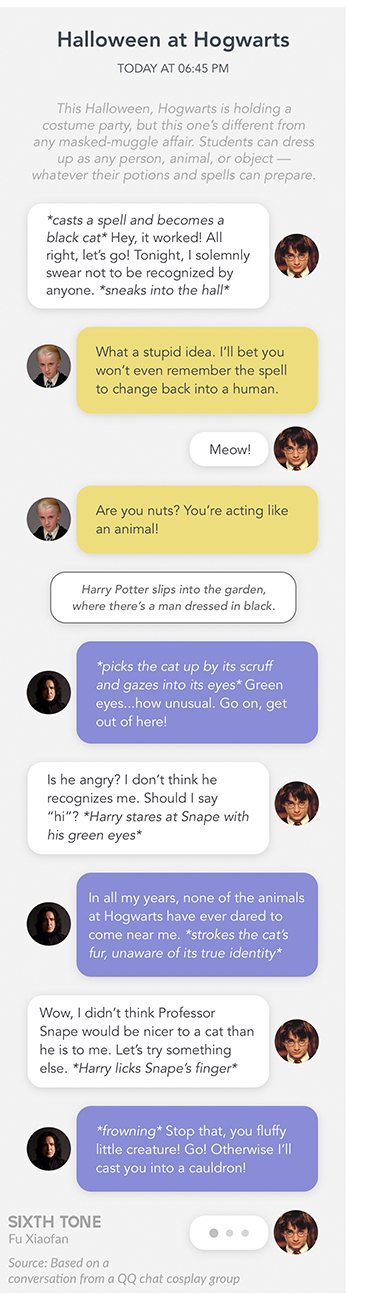

Unlike more traditional cosplay, in which people dress up in elaborate makeup and costumes, these participants don’t move away from their keyboards. Instead, chat cosplayers head online — spending hours living as fictional characters or real-life celebrities and chatting with other like-minded strangers. It’s not dissimilar to a real-time fanfic writing session, when cosplayers must stay true to the original characters, though the plots may also significantly deviate. For instance, while Liu’s Snape is in love with the series’ villain Voldemort — an alternative storyline that’s unpopular, even with the chat cosplay crowd — there’s no evidence of anything romantic between the pair in the original series.

There are countless chat cosplayers in China, though there’s no way of knowing the exact number. Many register multiple cosplaying accounts, mainly on two social media platforms: Baidu Tieba, China’s answer to Reddit, and messaging app QQ. On Baidu Tieba alone, there are around 90 million posts about chat cosplay, some of which have thousands of replies. In a trending topic on microblogging platform Weibo last year, chat cosplay was listed among the key terms to know for those wanting to understand today’s teens.

It’s not hard to get into chat cosplay, but there are rules you must obey. First: Adopt a character — either original or established — known in the cosplay community as “wearing a skin.” Second: Be familiar with your “skin” and thoroughly understand the backstory. Third: Set the scene. It could be a location mentioned in the original work, or another time and place altogether. Fourth: Get chatting, whether it’s posting a monologue — a practice known as “self-acting,” or splitting off with a few players for “group-acting.”

Many chat cosplayers — Liu included — consider themselves funü or “rotten women,” a term for straight women who have innocent fantasies about same-sex romances between male characters or stars. Many funü believe same-sex love between two men is more interesting than same-sex love between two women, or even heterosexual love. Playing a man in chat cosplays gives many such women the chance to take on roles they might not be able to have in real life, such as FBI agents or warriors — though they will still take on female roles when group-acting.

Katrien Jacobs, associate professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong who specializes in internet culture and sexuality studies, says that stories with gay themes are popular with young, mostly heterosexual women, who often see the stories as an outlet for their own sexuality. She says chat cosplay is usually a harmless and creative way to learn about sex and romance. “It’s not education from above: It’s their own education — we call it peer education. It’s quite innocent,” Jacobs says. “Young people talk about sexuality among each other, though it could be completely wrong. They tell stories and make jokes about it, and that’s how you learn.”

Liu’s favorite relationship — the imagined romance between Snape and Voldemort — is far less popular than fanfic favorites Draco Malfoy and Potter, or Snape and Potter. “For chat cosplayers, being a fan of an unpopular coupling is a little bit lonely, because it’s very hard to find a like-minded person to chat with,” Liu says. “But as soon as you find one, it feels like falling in love.” Liu still remembers meeting her Voldemort — also played by a woman — and chatting with him day and night both in and out of character. “He proposed to me and we got ‘married’ immediately,” she says. “You could call it a flash marriage.”

Since the betrayal, she’s become more focused on cosplaying as “Game of Thrones” hero Jon Snow. During weekends and holidays, she spends whole days chatting in her favorite skins, lost in a shared imaginary world. With her fellow cosplayers, she created absurdist scenarios: What if Jon Snow wakes up as his sister’s pet wolf? Would he get along with the family’s other pets?

All that time online takes a toll on Liu’s real life, however. Liu’s boyfriend often complains that Liu spends too much time cosplaying. He can’t understand why she wants to keep talking to people, most of whom she’s never met. “In his eyes, there’s no difference between our chats and full-on delusions,” Liu says.

But Liu is unmoved: She sees the chat group as a safe haven, giving her a chance to get closer to her favorite characters. “Chat cosplay allows me to walk into the world I love, where I can use my imagination to give characters alternative storylines,” she says. And despite her break-up, Liu believes cosplay is a good way to make real-life friends. “We treat other people with respect, because they’re wearing our favorite skin and we’re sharing such brave new words — but everyone is wearing a mask,” she says. “In reality, we’re just normal, conventional people.”

Other cosplayers draw inspiration from real people. Liu Xiaobing — who lives in the city of Hangzhou in eastern Zhejiang province, and goes by her nickname Bingbing — cosplays as Chinese singer Lu Han. On Oct. 10, 2014, Lu Han filed a lawsuit to nullify his contract with K-pop band EXO — a day Bingbing describes as the darkest in her life. The 14-year-old cried all day and night, distraught that she would never again see him onstage with his South Korean bandmate Oh Se-hun.

In July this year, Bingbing stumbled on screenshots that appeared to show the pair reminiscing about the times they’d shared. “I was so excited that I read it twice, but later I felt a bit strange — why was it all in Chinese?” Bingbing says. Eventually she realized it was just from a chat cosplay.

Although the screenshots weren’t real, they triggered her interest in chat cosplaying. Over the summer, she typed up a paragraph and sent it off to a chat cosplay group, attaching her profile: “Main skin: Lu Han. Seeking: Oh Se-hun, urgently!” Soon, Bingbing had received around 20 friend requests, but she accepted only one from a 15-year-old girl who called her hyung, the Korean word for “older brother.” “Hyung — that’s how Se-hun really greeted Lu Han. I thought she would be a great Se-hun.” Bingbing’s Lu has been talking to Se-hun ever since.

Chat cosplay fulfills a psychological need, says 31-year-old Zhu Yi, who launched a chat cosplay app in 2015 called “The Celebrities’ Timeline,” the largest and most popular app of its kind. The app’s interface mimics a social messaging app, allowing fans to imagine what their idols would post and how they would interact. “[Teenagers] like daydreaming, want to express themselves, love a little danger, and are lonely,” Zhu tells Sixth Tone.

Because around 85 percent of the app’s users are teenagers, the app takes steps to protect them. Zhu imposed a ban on pornographic content to make his app “as clear as water.” His 20-odd employees check the conversations and content every day in case there are any erotic conversations between underage cosplayers, and to detect words deemed sensitive, such as “bitch” and “slave.” Users aren’t allowed to share personal contact information, a measure aimed at protecting underage users, and encouraging users to stay on his app.

But not every young chat cosplayer wants the added layer of protection. Jiang Jie, a 16-year-old cosplayer in Shanghai who goes by her online username Jiangli, tells Sixth Tone that nearly all of her conversations will end with a virtual kiss — or even sex. “It’s exciting, isn’t it?” says Jiangli, who has been cosplaying for two years. Like Liu and Bingbing, she identifies as straight, though many of her romantic chats are with other female cosplayers. “I could only have this kind of conversation with girls … and we’d need to be the same age,” she says, before quickly adding: “And we must be really familiar with each other.”

When Jiangli began trying more romantic interactions, she was a little shy, but now she thinks her online fun is not a big deal. “It’s not real, and it’s not me who’s doing it — I just want my [online persona] to do it.” Like Bingbing, Jiangli’s parents don’t know what she gets up to online. “Why would I tell them what I’m doing?” she says. “They think I’m an innocent girl who covers her eyes whenever she sees someone kissing on TV!”

If her parents knew, they might have reason to be concerned: Writing erotic stories can land you in jail in China. In 2014, 20 female writers known for writing boy-love fanfic were arrested, and in 2015, another female writer known for writing online erotica faced criminal charges. But for the most part, the young cosplayers’ descriptions of love and sex seem innocent and childish, as if they’re figuring out what romantic relationships are like. The niche nature of the subculture — and the stringent restrictions put on app users — means the chat cosplayers haven’t yet come to the attention of the authorities.

Hu Xufeng, a graduate of civil engineering in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, is one of the rare male chat cosplayers. “If you do chat cosplay, you will find that girls are better at flirting,” says the 23-year-old, who cosplays as characters from Japanese anime “Naruto.” He’s tried to introduce chat cosplay to his roommates, but they rarely show interest. “Most men are more interested in esports than word games.”

To Hu, chat cosplay is a way for him to express the soft, gentle, and sentimental side of his personality that he doesn’t feel comfortable showing to his male friends. “Last year, when the first snow fell, I wrote a long post describing it,” Hu says. “Whenever something happens in my life, I share it online under the skin of one of my favorite characters. [Cosplaying] makes me feel like I’m living another person’s life — that’s the most interesting part of chat cosplay.”

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: Fu Xiaofan and Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)