3... 2... 1... Blastoff? Chinese Startups Gun for SpaceX’s Crown

SHAANXI, Northwest China — As our van rumbled deeper into deep, mist-shrouded mountains, the phone signal flickered and died. In the front seat, a stern PR officer swiveled and told the carload of journalists not to take any more photos. Beside him, the middle-aged chief technology officer of LandSpace, a Chinese private rocket company, appeared much more relaxed.

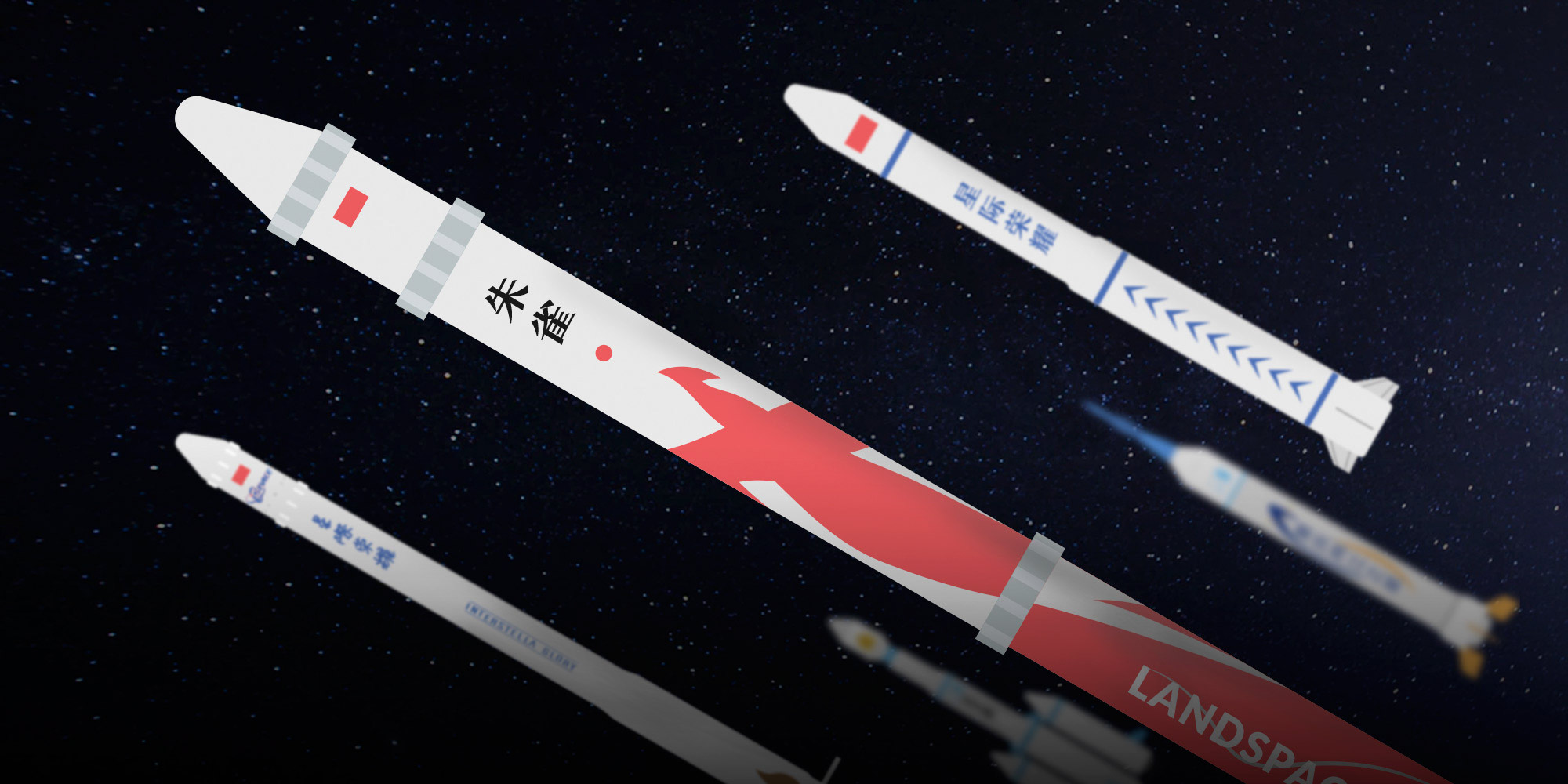

The van finally stopped in front of a former munitions factory. Inside, people in white lab coats rushed in and out of a door, behind which stood several sections of a huge red and white cylinder: Zhuque-1 (ZQ-1), LandSpace’s flagship rocket. On Oct. 27, LandSpace plans to launch ZQ-1 into space. If successful, it will be the first time that a Chinese private rocket company has delivered a satellite into orbit.

If they fail, it will no doubt bolster critics of both LandSpace and China’s fledgling space launch business. For all the industry’s ambition, innovation, and self-confidence — traits that bring inevitable comparisons to the world’s market leader, Elon Musk’s SpaceX — Chinese space companies are often accused of low profitability, irrelevance, and reliance on technology that they haven’t developed themselves.

LandSpace claims that ZQ-1 will eventually provide standardized launch services to companies looking to ferry small satellites into low Earth orbit — a wide range of altitudes where most commercial satellites are deployed. In doing so, the company is emulating the bulk of SpaceX’s business model: The American company charges state and commercial organizations a fee to launch satellites into orbit with its reusable Falcon rocket series.

LandSpace was established in June 2015 and today boasts nearly 200 employees. The company is headquartered in Beijing; has a research and development center in provincial capital Xi’an, as well as a manufacturing base in eastern China’s Zhejiang province; and plans to launch ZQ-1 from an arid corner of northwestern China’s Gansu province. The firm is helmed by Zhang Changwu, a 35-year-old in pressed shirts and square-framed glasses who radiates an almost disarming confidence in the success of ZQ-1’s maiden launch. “It carries great meaning, not only to China, but also to the entire private rocket industry,” he says.

From there, he says, LandSpace will aggressively move into the global market for space launch services — an industry expected to grow from $8.9 billion last year to nearly $30 billion by 2025. “Within a decade, LandSpace will be one of the world’s top three companies in the low-orbit launch market,” Zhang says — no small feat in an industry including SpaceX, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic.

Likewise, LandSpace’s soft-spoken CTO — who, despite his name being widely reported in Chinese media and readily available on the company's website, insisted on anonymity but allowed Sixth Tone to publish his position — exudes positivity. “ZQ-1 is just the company’s first step,” he says, explaining that LandSpace is also developing an engine called “Sky Magpie” to power the as-yet-unbuilt ZQ-2 rocket that will be twice as long, eight times as heavy, and strong enough to lift the equivalent of two SUVs into space — at a competitive price.

“For at least the first two years [following the October launch], ZQ-1 will cater to the micro-nano satellite launch market,” says LandSpace’s CTO from the cramped press room, referring to satellites that weigh less than 10 kilograms and are loaded onto rockets for delivery into space, and are frequently used in the communications, meteorology, and geo-exploration industries. “In a few years, once satellite companies are developing larger satellites … we will serve them with ZQ-2.”

But as with any rocket launch, things can go wrong. Unlike most private rockets on the world market, the 19-meter-long, 27-ton ZQ-1 uses solid fuel, which is an extremely flammable material more commonly used in military endeavors. A single spark could set the fuel ablaze and potentially cause an explosion. “Solid fuels … can easily lead to accidents during transportation and assembly,” says Dai Li, the president of the business incubator Westlake Maker Space and an enthusiastic observer of the private space flight industry. “A private company cannot let that happen. These fuels are also more damaging to the environment, which endangers a company’s public image.”

Launch failures are part and parcel of the rocket business, as SpaceX knows well. But if ZQ-1 fails, it will be yet another stain on the Chinese private space industry’s already rather ignominious reputation.

Rocketry in China can be traced back to at least 1958, when students at several universities in Beijing launched China’s first sounding rocket — instrument-carrying vehicles that do not enter orbit before falling back to Earth, which is usually within a few minutes after launch. Until the beginning of the 21st century, the central government commissioned and managed all space projects, even as the first private space companies emerged in the U.S. and other Western countries.

In January 2014, a college student in southern China, Hu Zhenyu, founded the country’s first private space launch company, LinkSpace. In November that year, the State Council — China’s cabinet — issued guidelines on how private businesses could research, develop, launch, and operate commercial satellites. And in 2015, China’s President Xi Jinping further endorsed the integration of Chinese rocketry’s civil and military uses. Links between the state and private rocket companies remain largely opaque, but today, the country is home to around 10 private rocket companies, of whom i-Space, OneSpace, and LandSpace — in that order — have attracted the most investment. LandSpace is the only company of the trio yet to launch its first rocket.

In April this year, the Beijing-headquartered i-Space successfully launched a sounding rocket, the Hyperbola-1S. A month later, OneSpace — a firm with offices in Beijing and Chongqing — launched a similar product, the OS-X. Hyperbola-1S reached a height of 108 kilometers before falling back to Earth; the OS-X only reached 38.7 kilometers. (By comparison, one of China’s 1958 sounding rockets reached 74 kilometers.) Both launches garnered much media fanfare.

LandSpace plans to launch the ZQ-1 to at least 500 kilometers. And some of the company’s future plans are more fanciful: In the long run, LandSpace intends to develop so-called heavy-lift launch vehicles — rockets capable of lifting 20 to 50 tons of payload into low Earth orbit, where most manmade satellites circulate the Earth. Generally speaking, the larger a rocket’s payload capacity, the cheaper it is to carry 1 kilogram of freight, allowing companies to price their launches more competitively. Heavy-lift rockets may even allow LandSpace to compete with current industry titans, including SpaceX.

As if that wasn’t enough, Zhang Changwu, LandSpace’s CEO, has another goal in mind, too. “Ultimately, we want to build a cross-continental spaceplane that can take travelers into suborbital space,” he says, echoing an idea that SpaceX has also floated.

But Chinese observers don’t entirely buy into the domestic space industry’s blue-sky thinking. Jin Zhonghe, deputy director of the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Zhejiang University, calls LandSpace’s planned spaceplane “commercially unrealistic,” citing their high cost and low profitability. “If this is their final goal, I suggest they change it,” he says. “A commercial company needs a more practical aim, not just a slogan.”

Jin says that small-lift launch vehicles — the technical term for rockets like ZQ-1 that can lift up to 2 tons of payload into orbit — often struggle to make money. “I just don’t think there’s a seller’s market [in China] for micro-nano satellite launches,” he says. Although the global market is reportedly growing by more than 20 percent annually, China’s domestic market remains dominated by state-owned enterprises that operate commercial launch services to private businesses at similar or slightly higher prices than SpaceX.

LandSpace’s CTO refused to weigh in on ZQ-1’s estimated profits when Sixth Tone inquired in September, saying only that the company would reveal the figures at some point in the future. Zhang, LandSpace’s CEO, said that the ZQ-2 does not yet have a launch price, but the rocket’s reusability will give each model a projected lifespan of 20 to 100 launches, cutting costs and making pricing more competitive. Companies typically pay around $62 million for a launch on SpaceX’s Falcon 9. The Chinese government has not officially disclosed the price of launching a satellite on the state-owned Long March 3, but it is speculated to be between $60 million and $70 million. LandSpace has not disclosed how much it charged for ZQ-1’s impending launch.

Dai, the business incubator, thinks companies like LandSpace should focus on developing rockets with broader public uses — “like SpaceX, who conquered the world with a single engine.” He’s referring to Merlin, a family of engines developed by Musk’s U.S.-based firm that propels most rockets in the company’s flagship Falcon series. The 91-ton vacuum-thrust engine is fueled by liquid oxygen and RP-1 — a kind of refined kerosene — making it comparatively eco-friendly. No Chinese private company has yet managed to build a liquid-fuel engine on a similar scale.

While LandSpace’s executives struggle to explain how the company will turn a profit, other Chinese space companies have been accused of pursuing totally irrelevant projects. For one thing, the aeronautical community is split on the modern-day importance of sounding rockets. Guang Lixia, an engineer and rocket industry watcher, pointed out that NASA frequently launches sounding rockets in order to take measurements of high-altitude air. Yao Bowen, a spokesperson for i-Space, tells Sixth Tone that building a sounding rocket is a “trial” that the company must go through. “The space industry grows by making mistakes,” he says. “Every company has its own strategy.”

But others dismiss the launches as primitive and unnecessary. “Sure, a few private companies have launched their own rockets,” says Zhao Jincai, a member of the Shanghai Aerospace Systems Engineering Research Institute. “But that is not real space flight.”

“For businesses, the biggest problem is not sending satellites into orbit, which could be achieved with proper money, time, and technicians,” says Jin, the professor at Zhejiang University. “What’s really hard is developing a commercially competitive carrier rocket, which involves proper product positioning that will find enough customers in the future. It also means controlling manufacturing and operating costs — not only launching the satellites, but also making real profits.”

Regardless of their scientific importance, both i-Space and OneSpace received millions of yuan in new investment following their recent launches, leading some to question whether the companies were merely courting venture capitalists with eye-catching projects that are actually comparatively easy to achieve. Yao, i-Space’s spokesperson, denies that the launches of sounding rockets are merely a fundraising exercise. “First of all, i-Space has very powerful investors and has no problem raising money,” he says. “And second: What is wrong with fundraising, anyway?”

In their post-launch press releases, i-Space called the Hyperbola-1S “China’s first privately launched sounding rocket,” while OneSpace’s CEO, Shu Chang, took pains to describe the OS-X as “China’s first privately developed” one. Shu’s phrasing was perhaps a subtle dig at the source of i-Space’s technology: After the company took merely two months to develop the Hyperbola-1S — an extremely short timespan in the complex field of rocket science — Chinese media outlets raised questions about whether the company actually owned the technology or had merely purchased it from a third party.

Dai, the business incubator, claims that instead of developing their own technology, certain Chinese private rocket companies buy retired missiles from the military and launch them under their own names. “If they’re trying to get into the space business, these actions can be passed off as a stage in the learning process,” he says, “but the companies should not rebrand them as their own products.”

But Yao says the reality of technology transfer is far less transactional. He estimates that 60 percent of i-Space’s 150 or so employees are recruited from state-owned enterprises, where some have researched missile technology for decades. “It’s like when a steak chef moves to a new restaurant — they’re somewhere new, but their steaks still have the same flavor.”

LandSpace knows that pilfering the state’s rocket experts can be controversial — not least when it conflicts with China’s national interests. In September, a document from the Xi’an Aerospace Propulsion Institute circulated online, claiming that the recent resignation of their deputy design director, Zhang Xiaoping — who had taken up a new job at LandSpace — would impact the development of a 480-ton liquid-fuel engine designed as part of a state-sponsored manned moon landing slated for completion in 2036. (The institute later issued a clarification saying that the claims in the document were exaggerated.)

LandSpace declined to comment on Zhang Xiaoping’s appointment with Sixth Tone, but Zhang Changwu, its CEO, told Sixth Tone that nearly 70 percent of staff come from state-owned companies. The company said that the CTO’s reluctance to speak fully on the record was due to a “confidentiality agreement” signed prior to joining LandSpace.

For now, LandSpace’s larger ambitions are far from being realized. Zhang Changwu, the CEO, says that LandSpace is limiting itself to challenging U.S. companies in the market for medium-lift launch services — a market in which China’s share dropped almost to zero in 2017. LandSpace also plans to test the Sky Magpie, its first liquid-fuel engine, before the end of this year, with a view toward launching the ZQ-2 by 2020.

i-Space plans to test a liquid-fuel engine in 2019 and says it will focus on small-lift launch vehicles. OneSpace says it is developing small-lift rockets for high-frequency, low-cost commercial launch services.

It is T-minus 10 days until LandSpace launches the ZQ-1. As three years of hard work approaches an exciting conclusion, LandSpace’s CTO, keeps his eyes trained on the company’s prospective future competitor. “We might not measure up to SpaceX at the moment,” he says, “but when SpaceX was our age, they couldn’t do what we’re doing now.”

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone)