The Rise of China’s Working-Class ‘Palaces’

This article is the first in a three-part series on the cultural spaces that have shaped China’s working class. The second can be found here.

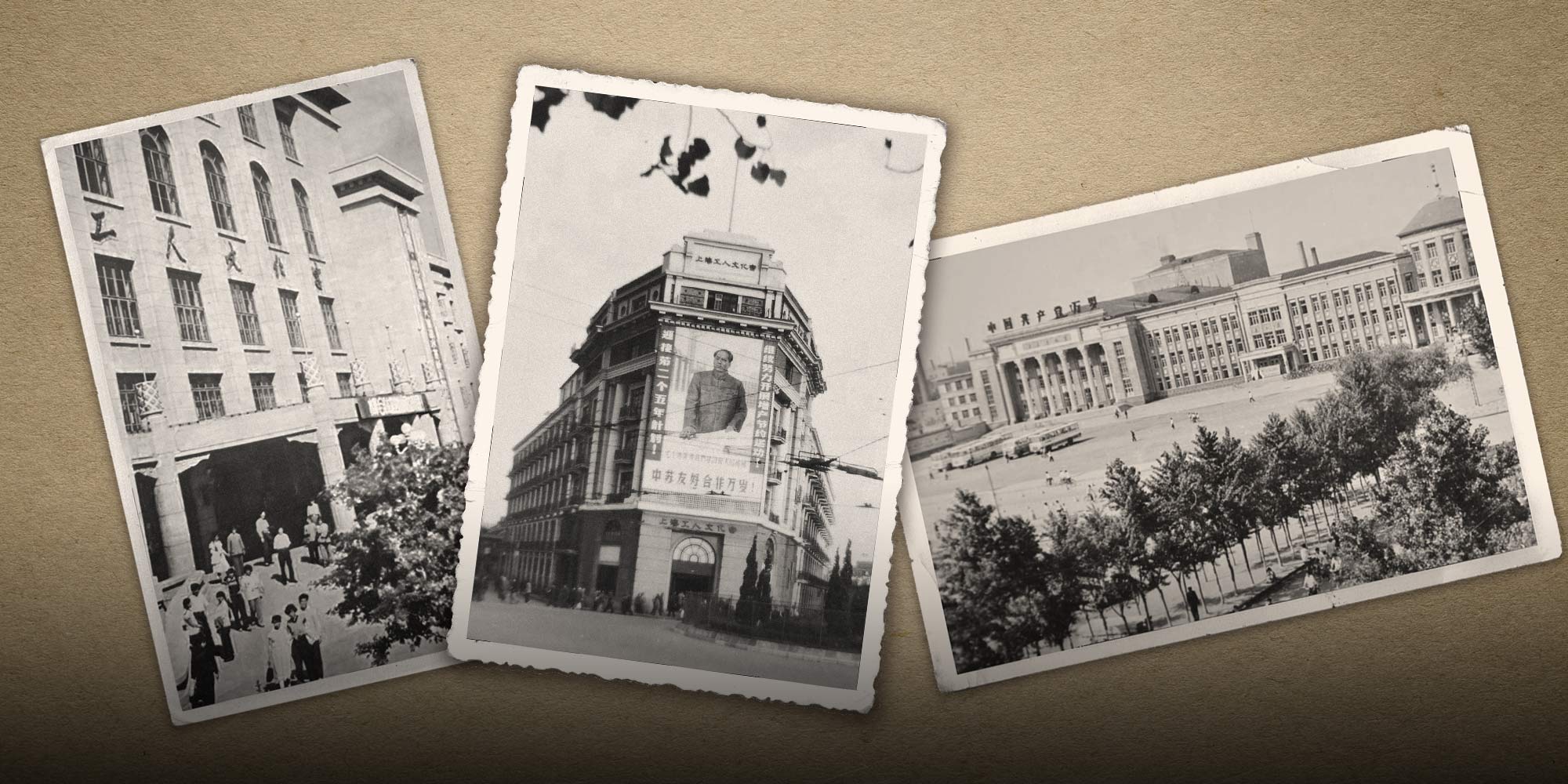

They’re ubiquitous and occupy some of the best, most striking real estate in all of China. Yet today they’re all too often empty, run down, or leased out: hulking shells of their former selves, monuments to a bygone experiment in social engineering. I’m of course referring to China’s workers’ cultural palaces. The social and economic status of China’s working class has fallen dramatically over the past 40 years, but there was a time when blue-collar proletarians were expected to lead the country’s revolution into the future, and vast spaces were built or set aside solely for their education, entertainment, and overall betterment. And the most iconic of these spaces was doubtless the workers’ cultural palace. By tracing their rise and fall over the past seven decades, we can observe some of the tremendous changes that have taken place in urban China in that time, and how they have reshaped the relationship between worker and society at large.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Chinese industry and urban planning had a distinctly Soviet flavor, and the country’s cultural palaces shared in this legacy. The concept itself has its origins in the “people’s house,” a type of institution often established by liberal charities or individuals in Russia around the turn of the 20th century to provide entertainment and education to intellectuals, petty civil servants, students, soldiers, and workers. As Russian politics grew more radical, these people’s houses became community education centers for the working class.

Unlike in the Soviet Union, the cultural palaces of the People’s Republic of China were mostly founded in repurposed landmarks, rather than new buildings. In 1950, the Imperial Ancestral Temple in Beijing’s Forbidden City was converted into the Working People’s Cultural Palace. That same year, in the nearby city of Tianjin, a stadium in the former Italian concession once owned and run by the Mussolini family was renovated into the Tianjin Workers’ Cultural Palace. It bears an inscription written by the city’s then-mayor, Huang Jing, exhorting workers “to work like soldiers and relax with culture.” In Shanghai, a hotel adjacent to the old racetrack in the city’s central business district was repurposed into what the city’s then-mayor referred to as “a school and paradise for workers.”

Repurposing preexisting structures was a practical decision, given the country’s weak economic foundations. But it also embodied an important concept in contemporary discourse: fanshen, a word that can mean to “turn over” or “reinvent.” By converting Confucian schoolhouses or bourgeois entertainment complexes into cultural venues for workers, socialist China was able to remake the social power relations and spatial attributes of its cities. In the space of just a few years, symbols of feudal and colonial power were transformed into “secular temples” of a worker-led nation.

The underlying goal here was the nationalization of workers’ leisure time. In 1950, the state-affiliated All-China Federation of Trade Unions declared that the main tasks of the country’s new workers’ cultural palaces and clubs were to disseminate political propaganda, spur on production, provide cultural and technical education, and to organize cultural and artistic activities for workers and their families in their downtime, in that order. In a sense, they were factories of a different sort, tasked with producing the mindsets and ideologies required for socialist industrialization: patriotism, collectivism, enthusiasm for production, and technological innovation. The rural Chinese transplants flooding cities were, by virtue of contact with these spaces and the practices of collective labor and leisure, expected to develop into both competent industrial workers and conscientious members of socialist society.

Early workers’ cultural palaces were not limited to being simple ideological vessels for the new regime, however. Backed by government funding, the larger palaces could host thousands of people and boasted a range of facilities, from libraries and rooms for chess and table tennis to gyms and even small theaters, all available free-of-charge to workers. Workers used these facilities to make friends, fall in love, chat, or otherwise simply pass the time.

In an interview, a retired factory worker from a steel city in China’s Northeast recalled: “Every day after work, I would head straight to the workers’ club. Back then, it was full of life, mainly acting as a venue for (our) amateur theater troupes. My wife and I met in an amateur Ping opera troupe. An old man taught the two of us the music, and then we began to practice and chat with one another. Over the course of several meetups, we became partners.”

Because the palaces had no commercial purpose and didn’t offer any consumer goods, they broke down some of the barriers to cultural consumption that had prevailed under capitalism, rendering culture accessible to workers who didn’t possess cultural capital, and restoring its status to that of a product of the people. Not just amateur groups, many professional theater troupes and even world-renowned artists like Mei Lanfang performed at workers’ cultural palaces during the early socialist period, stimulating exchanges between professional artists and working-class amateurs.

In short, while these spaces may have been charged with the task of political indoctrination, that doesn’t mean they failed to deliver on their other promise: providing workers with time and space for leisure outside the dehumanizing and alienating conditions of factory life, thereby allowing the working class to achieve a certain degree of self-education and cultural autonomy. Their very existence served to agitate in favor of a collectivist culture, in which everyone could contribute to popular entertainment, and everyone could benefit, without concern for financial profit.

In the post-Mao era, that culture has grown increasingly commercialized and digitalized, while the workers’ cultural palaces have been hollowed out. Their legacy lives on, however, in the grassroots cultural and entertainment groups still ubiquitous in Chinese cities today. Whether square-dancing grannies or park-based opera enthusiasts, these groups represent continuations of a bygone collectivist cultural lifestyle — and, perhaps, alternative visions of a cultural industry once again freed from profit motives.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: From left to right: archive photos of workers’ cultural palaces in the cities of Changchun (1960s), Shanghai (1950s) and Mudanjiang (1980s). Visual elements from Kongfz.com and VCG, edited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)