China’s National Soccer Team Accepts First Naturalized Citizen

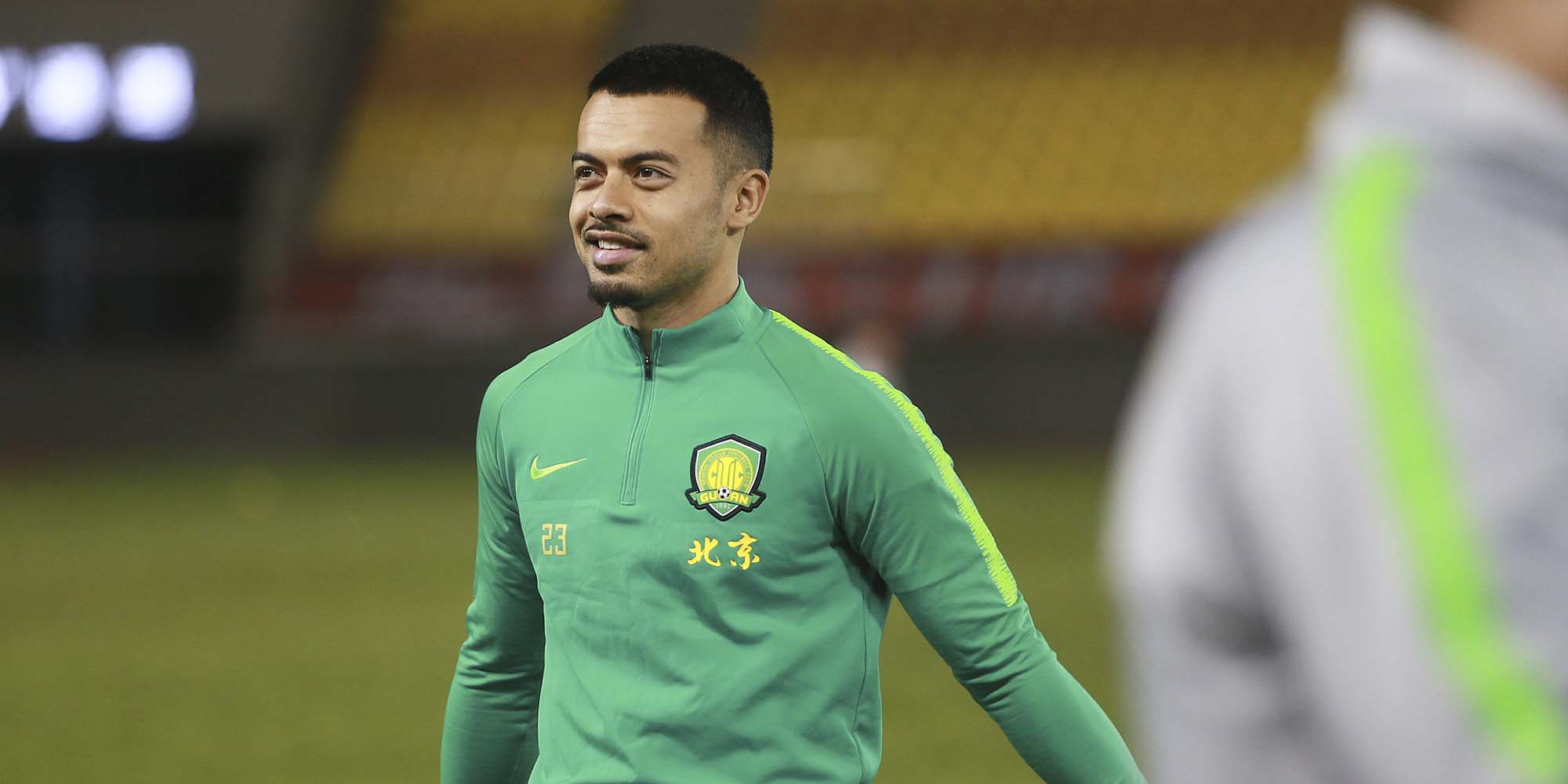

Nico Yennaris, a 26-year-old professional soccer player of mixed Cypriot-Chinese ancestry, has become the first-ever naturalized citizen to join China’s national team.

The London-born Arsenal youth league product was included among 24 players selected for the Chinese national team, according to an announcement Thursday. The roster was finalized ahead of a friendly matchup against the Philippines scheduled to take place next week in the southern Chinese megacity of Guangzhou.

Yennaris — whose mother is Chinese — grew up in East London and began his soccer career at Arsenal’s youth academy and the second-division English team Brentford F.C. In January, Yennaris gave up his British citizenship to become a Chinese national and transferred to Beijing Sinobo Guoan F.C., where he plays as a defensive midfielder.

The inclusion of a naturalized citizen on China’s national team is a historical first, but Yennaris may soon be joined by other foreign-born players who can’t even claim partial Chinese ancestry.

On Monday, domestic media reported that Brazilians Ricardo Goulart and Elkeson — who’ve played in China’s Super League for many years — had agreed to become naturalized citizens of the country. This means that China’s national team could be able to add its own token Brazilian player as early as September.

The news of Yennaris’ inclusion on China’s national team — as well as the wider topic of naturalization — has sparked online discussion about Chinese identity. While some netizens have made racially tinged remarks about Yennaris’ skin tone, others have said they can accept him because of his partial Chinese ancestry. Meanwhile, still other netizens have worried that allowing foreign-born players might discourage domestic talent and questioned whether having the right DNA should be the sole factor making someone Chinese.

“Who is more Chinese: your so-called ‘half-Chinese person’ who has never been to China and doesn’t understand a word of Chinese?” commented one netizen under a related media post, referring to Yennaris. “Or a total foreigner who has lived and worked in China for five years and lifts up (our national flag) when he wins?” — a likely reference to the Brazilian player Elkeson.

In March, the Chinese Football Association, or CFA, issued a notice saying that foreign soccer stars naturalized to play in the Super League should be able to recognize the Chinese flag and sing the national Anthem, as well as study the country’s language, history, culture, and politics. “They must have a Mandarin learning plan set for them, and have the patriotic spirit nurtured within them,” the notice said.

Naturalizing players so they can join national sports teams is standard practice internationally, but the CFA has long resisted the trend. Only last September did a Chinese team declare its intention to bring in naturalized players — suggesting the CFA had given its tacit approval. Since January, a string of foreign players with Chinese ancestry have joined Chinese clubs and initiated the naturalization process.

Naturalization is especially appealing to Chinese teams because it lets them reel in foreign talent that doesn’t add to their three-foreign-player limit, said Cameron Wilson, the founding editor of Wild East Football, a media outlet covering the sport in China. But the policy shift is also aimed at improving the fortunes of the national team.

“It’s believed the powers that be are permitting this policy because they believe it could benefit the national team farther down the line,” Wilson told Sixth Tone.

The policy’s implementation has been far from smooth, however. Before the Chinese Super League kicked off in March of this year, naturalized players were banned from competition, without explanation, only to be allowed to resume playing after three games.

“When you see this in China, you know there’s been a lot of internal wrangling over this policy,” said Wilson. “It shows there’s a lot of debate about it in the system.” Even top officials in Chinese soccer have publicly questioned whether allowing naturalized players is the right approach for the country.

Wilson thinks the change of tack may help challenge some people’s narrower notions of Chinese identity, though he conceded that naturalization could also be viewed as a desperate way for China to improve the caliber of its national squad.

As for the two Brazilian players, it’s “very questionable” whether they truly have enough of a connection to China, said Wilson. Naturalizing mixed-race players has already proved controversial, he explained, and in light of this, doing the same for players with no ancestral ties would be “fairly revolutionary.”

“It’ll create some discussion, and maybe make Chinese people feel they should be more inclusive about what defines Chinese identity,” said Wilson. “Is ‘Chinese’ defined purely by blood, by ethnicity? Or can someone become Chinese because they spent so long in China that they’re effectively as Chinese as anybody else?”

In the absence of the two Brazilians — whom Wilson ranks among the best players in Asia — national team additions like Yennaris should have a modest impact. “I think it’s going to benefit them,” he said, “but it’s not going to make them into a good team overnight.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated when the Chinese Super League’s temporary ban on naturalized players was imposed.

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: British-born soccer player Nico Yennaris trains with his Chinese team, Beijing Sinobo Guoan F.C., in Wuhan, Hubei province, Feb. 28, 2019. VCG)