The Viral Internet Doctor Getting the Sickest Clicks

GUANGDONG, South China — For 12 years after graduating from medical school, Pei Honggang spent his days among anxious parents and sick kids at Shenzhen Children’s Hospital. A pediatric surgeon by profession, he performed operations on countless children in the southern Chinese city. It was the job he’d always wanted, ever since his student days.

But two years ago, Pei quit his job. He cited stress, low pay, frequent conflicts with patients’ families, and the risks associated with treating infants, who are often incapable of communicating their discomfort.

Pei, who by then was a well-known online figure with over 500,000 social media followers, explained his rationale in a March 2016 article simply titled “I Resigned.” He wrote: “Faced with realities that I cannot change, I can choose one of two paths: stay and put up with it, or get out of here.”

When he posted the piece on WeChat, China’s most popular messaging app, his words went viral: Thousands of readers left messages admiring his courage, while others asked what he planned to do next. That turned out to be the launch of a WeChat public account offering users one-to-one consultations with doctors via their mobile devices. Despite the support of his fans on social media, Pei has struggled to justify his decision to leave a stable public hospital job to his family. “It’s been a lonely road,” he says. “Even now, I still feel like I’m on my own.”

Shenzhen is home to an estimated 3.75 million residents under 14 years old, and the city sees an average of 200,000 newborns a year. According to the municipal health authority, Shenzhen has one pediatrician for every 1,875 children. Although this ratio is roughly equal to the national average, it is far lower than in developed countries like the United States, which boasts one pediatrician for every 625 children.

Pei’s original plan was to open his own private pediatric clinic, but he balked at the enormous startup costs of around 5 million yuan ($788,000). Instead, he founded Yaeher Health, an online platform that connects patients with doctors, in May 2016. Like similar doctor consultation apps in China, Yaeher allows users to search specific medical symptoms or the names of approved doctors. The platform then connects patients to recommended clinicians in return for a fee — usually between 30 and 600 yuan, based on the doctor’s specialization and experience level. Patients and doctors then communicate with each other via Yaeher’s WeChat account.

Today, Pei and his nine-person team work out of a cramped office in a quiet part of Shenzhen. While Yaeher started out by offering exclusively pediatric services, nowadays it features more than 300 doctors specializing in a wide range of common ailments. More than 600 consultations take place on the platform every day, Pei says, adding that more than half of his clients arrange follow-up appointments with the same doctor.

Yaeher’s success has convinced Pei to revisit his original plan of opening a pediatric clinic. In March, he began hiring fellow specialists. But his task was made all the more difficult by a national shortage of pediatricians: A government white paper issued in May 2017 stated that more than 14,000 of the country’s pediatricians had left their jobs in the previous three years — nearly 11 percent overall. More than half of them were under 35 years old.

That’s exactly the group of pediatricians Pei wants to hire — young doctors who nonetheless have at least five years of clinical experience in a top-tier public hospital. But many of these “lost” pediatricians opt to transfer to other hospital departments, further their studies abroad, or join pharmaceutical companies; comparatively few continue practicing the same discipline as before, according to a study led by the Chinese Pediatric Society.

Pei hopes that Yaeher’s competitive salary package can persuade some to stay. So far, he has hired four doctors but is searching for several more. The clinic is slated to open in August this year in downtown Shenzhen.

Sixth Tone spoke to Pei about his business venture and the ongoing debate about public versus private health care in China. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: You now have around 2 million followers on social media. What first inspired you to interact with people online?

Pei Honggang: In 2011, an event took place that doctors and the media would later call the “80 cents incident.” A six-day-old baby was brought to our hospital with suspected constipation, and we recommended that the boy undergo surgery. But eventually, the family visited a hospital in [provincial capital] Guangzhou that instead prescribed them medicine that only cost 80 cents. The family then claimed that the drug did the trick, and when the incident was exposed by local media, it sparked a lot of controversy.

I started using [Chinese microblogging site] Weibo because I wanted to explain the scientific basis behind our hospital’s recommendation. I realized then how important it is for medical professionals to make their voices heard. At first, I had only a few hundred followers and mainly wrote about the loopholes in [China’s] public health care system. But I figured these articles wouldn’t change anything, so I decided to write something about my own specialty, pediatrics.

Sixth Tone: You write a lot about how to care for children who have various illnesses and the medical knowledge behind each treatment. How do you view the ways that Chinese parents today learn basic medical knowledge?

Pei Honggang: To be honest, I don’t see any government effort to popularize medical awareness among citizens. In the U.S., the American Academy of Pediatrics maintains websites to tell the public how to care for sick children. In Australia, the Royal Children’s Hospital is leading similar efforts. However, in China, no such attempts have been made at the governmental level. Some hospitals use social media to spread medical knowledge, but in general, the quality is low.

This helps draw parents to my posts to learn what they need. There’s a real desire in China for this sort of content.

Sixth Tone: What do your followers mean to you? What were your thoughts when you decided to leave the public system?

Pei Honggang: I enjoy being a doctor; it brings me a real sense of accomplishment. As a surgeon, I could rapidly and visibly improve a sick child’s condition. But I always dreamed of building a clinic where patients and doctors could fully trust each other. My hundreds of thousands of online followers gave me the confidence to keep practicing medicine outside the public system.

Sixth Tone: You say that your ideal work environment is one built on trust between doctors and patients, but the picture in public hospitals is often different. Outpatient department doctors spend a matter of minutes with each patient, and this lack of communication leads to conflict and mistakes. Which issues do you think fundamentally impact the doctor-patient relationship?

Pei Honggang: In any service industry, there’s a chance that the person you serve has no faith in you. But doctors in public hospitals are part of the bianzhi system, which essentially gives them lifelong contracts with enviable social benefits, regardless of their individual performances. They are not part of the service industry. Essentially, in China’s public hospitals, doctors don’t really need to consider how their patients feel. They have so many patients that they don’t need to cultivate strong relationships with them. And their incomes aren’t affected by how many patients they receive.

But only two things matter in the private system: the doctors’ expertise and their service standards. That’s why I looked at the resumes of over 1,000 doctors who applied to Yaeher, but rejected 70 percent of them. The professionalism of our medical staff is very important. Our staff knows that we provide a service and that communication with patients is key.

Sixth Tone: Two years after launching Yaeher, you’re finally about to open your own clinic. Has your reputation as a well-known voice in the medical community been an advantage in the run-up to the launch?

Pei Honggang: Not really. I don’t think my online reputation has brought me this far — it’s more that I always emphasize the need to provide patients high-quality, professional services. Offline, it’s still a challenge to hire good pediatricians. When they’re in the public system, they often complain about low pay and heavy workloads. But when I offer them much higher incomes, they still refuse to leave. Government-supported hospitals offer much stabler jobs [than the private sector], and if you spend several years there, you feel insecure and afraid when given a real chance to leave it behind.

Sixth Tone: In the past five years, many doctors have left the public system to join private platforms, and some — like you — have started their own businesses. Do you think doctors have certain entrepreneurial advantages in the medical industry?

Pei Honggang: I wouldn’t recommend that doctors become entrepreneurs! Starting a company is completely different from treating patients. After I left the public system, I studied management and business operations from scratch. It certainly wasn’t easy. But the rapid development of the internet has made it possible for doctors to build up their own brands. Fortunately, every time one of us takes the plunge, we spur a little more change across the entire medical industry.

Correction: Yaeher Health is a WeChat account, not an app.

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

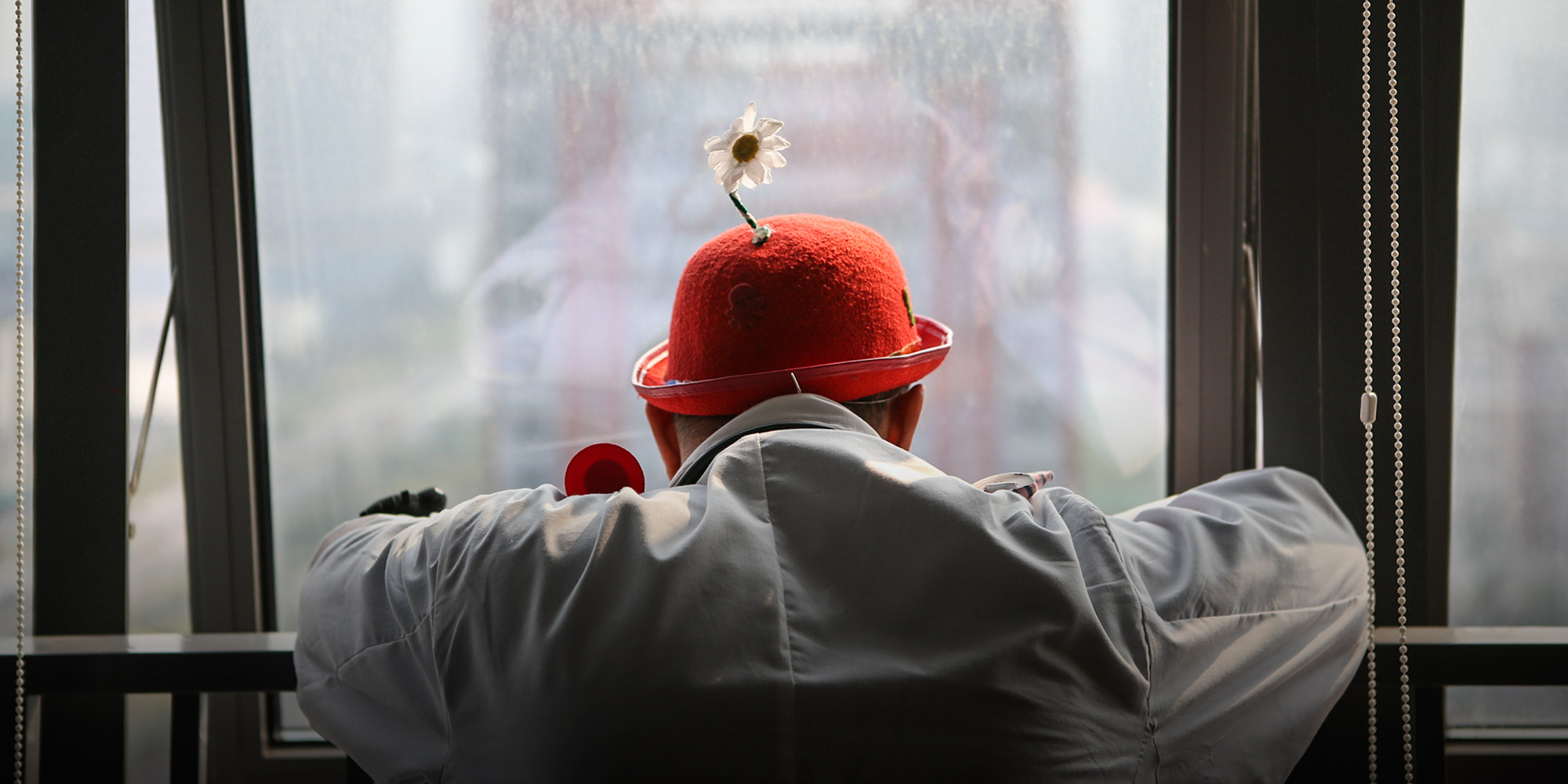

(Header image: A medical staff member wearing a clown’s hat looks through the window at a pediatric ward in Shanghai, Nov. 6, 2014. Jia Yanan for Sixth Tone)