The Former Doctor Fighting China’s Health Rumor Epidemic

Seaweed made of plastic bags, soy sauce that can lead to cancer, a blindness epidemic caused by cellphones that will strike in three years — a plethora of rumors spread online in 2017 and led many Chinese to worry. Some 500 million such rumors — more than half of them related to health and food — were identified and removed from WeChat, China’s largest social media platform.

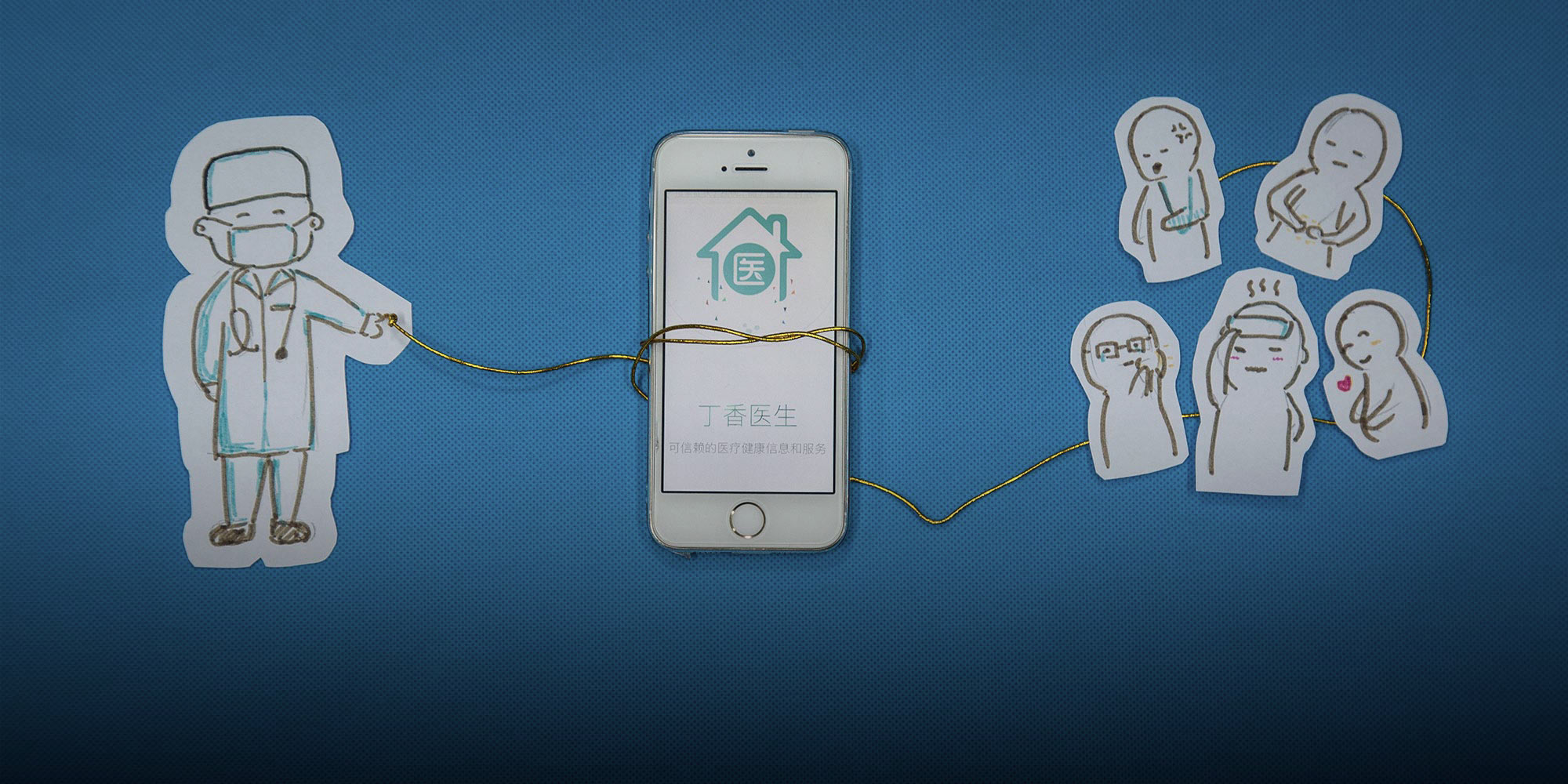

Chu Yang strives to counteract this wave of misinformation. In 2014, the former orthopedic physician founded Dingxiang Doctor, a new media platform that fights medical rumors with facts provided by real experts.

“The information gap between ordinary people and medical professionals is huge,” Chu tells Sixth Tone.

The case of a young cancer patient who was misled by an ad for treatment on Chinese search engine Baidu and eventually died was one of the first to highlight the issue in 2016. The following year, Shapuaisi, an eye care brand that generated 750 million yuan ($113 million) in eye drop sales in 2016, was accused of falsely advertising that its eye drops could cure and prevent cataracts; it was ordered by the food and drug administration to either prove its claims through clinical trials or amend its advertising.

Dingxiang Doctor is one of the most successful anti-misinformation platforms, with about 6 million followers on its main WeChat account. Most of its articles garner more than 100,000 views, with some even reaching 1 million. Four days after it published an article criticizing Shapuaisi, the eye care company’s stock price fell by its daily limit.

Chu spoke to Sixth Tone about the platform’s war against rumors and false advertising, and how easily the public is misled by social media, search engine results, and clickbait articles. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Why did you quit your job as a doctor to start a health-focused new media platform?

Chu Yang: As a doctor, I always felt the tension between doctors and patients and wondered why. Gradually, I found that the language doctors and patients use doesn’t match.

On the one hand, it’s because the Chinese education system doesn’t give us a common understanding of health, and there used to be no reliable sources on the internet. On the other hand, doctors are trained to speak professionally; we weren’t instructed on bedside manner, so we were often unable to explain things to patients.

I remember that I wasn’t able to recommend a place where my patients could look up basic health information themselves. This inspired the idea for Dingxiang Doctor. As for my own interests, I started writing popular science news articles while in university. As a doctor, I could help only a few people; working for Dingxiang Doctor enables me to help many more.

Sixth Tone: What kinds of rumors and misinformation are most common in China? Why?

Chu Yang: The majority of rumors are about food. As an ancient Chinese saying goes, “Food is the first necessity of the people.” Chinese people pay great attention to eating habits.

But traditional beliefs and food safety scares often give rise to misunderstandings. Traditional Chinese medicine has a strong cultural influence on society and has planted ideas of certain foods’ restorative properties in people’s minds. Some ideas, such as the theory that eating garlic can prevent cancer, have been proved false by modern medicine but continue to spread among the public.

Meanwhile, as the quality of life improves, people are paying more attention to health and sanitation. The past decade has seen some of the most serious food safety crises. Problems such as tainted milk have inspired conspiracy theories that certain types of food contain harmful hormones, additives, or chemicals.

Rumors about other issues, such as the dangers of radiation, are also common. Dingxiang Clinic [a medical practice under the same company that owns Dingxiang Doctor] once ran into trouble over plans to install an X-ray machine. Objections from neighbors who worried about the harm it might cause eventually forced the clinic to return the machine.

Sixth Tone: The elderly are particularly vulnerable to health misinformation. Do you see them as your target audience?

Chu Yang: Originally, our target audience was mainly young people, those with respect for science. But as our influence grew, many readers recommended our platform to middle-aged and elderly people they knew.

We then opened a separate WeChat public account especially for the elderly, with a tailored approach in terms of wording and visual presentation. Now, the company has dozens of specialized WeChat accounts with a total of 20 million followers.

Sixth Tone: What challenges do you encounter in presenting health knowledge to your audience?

Chu Yang: The most troublesome thing is to find a news angle. Every news meeting is like an exam, or a dissertation defense even. For a story on, say, why a certain skincare method is ineffective, the editor must outline opinions and gather reference material. We choose our topics carefully, using data to determine what kinds of stories people care about most.

Language is another challenge. We use metaphors and simple explanations to help people understand what we are talking about. Meanwhile, we also want each article to be interesting, which requires our team members to stop showing off their knowledge and start thinking from the reader’s point of view.

Almost every article has to go through peer review like at an academic publication, as the content usually requires professional knowledge. We invite doctors to serve as our writers and reviewers. The publication process is usually relatively short, about one to two weeks, as we have a large expert base. Over half of our staff have a medical background, which is rare for a news team.

Sixth Tone: Why did you decide to write about Shapuaisi? Have you faced any pressure as a result of the story?

Chu Yang: We brought the topic up in a news meeting, and it was approved very quickly. We found that there was a huge misunderstanding about the eye care brand: While the mainstream medical community doesn’t recognize the effectiveness of the brand in curing cataracts at all, the eye drops are advertised widely on television and make the company around 750 million yuan every year.

It took us longer than usual to publish the article, because we were very aware that Shapuaisi is listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. We checked every piece of evidence and ruled out any errors in logic. It took three weeks for us to finally publish the story. After publication, other media followed up, and the China Food and Drug Administration issued a notice asking the brand to stop making claims for which they had no evidence.

We did face pressure from outside our company. Before the story, Shapuaisi didn’t have a publicity department, but they established one right after it came out. As the company is from [eastern China’s] Zhejiang province, where we are also based, many [complaints] have come to us through various connections. However, from our CEO down to the rest of the staff, we share the same values, so this type of pressure hasn’t affected our judgment.

Sixth Tone: What’s the most memorable piece of reader feedback you’ve ever received?

Chu Yang: Once I visited a friend’s house, and a 50-year-old nanny working there asked me for my autograph. I was puzzled. She told me that she was an avid reader of Dingxiang Doctor and has recommended the account to people in her hometown. Dingxiang Doctor has a “health calendar” section in which we run sentence-long health tips that are easy to read. The woman was able to learn something new in just a few seconds per day.

This encounter made me realize that we are helping the people we want to help. We don’t wish to only serve the middle class and be so far from the grassroots. The people we most want to serve are those without higher education, as these are the people who fall victim to rumors and pseudoscientific information — these are the people who really need our help.

Editor: Denise Hruby.

(Header image: Shi Yangkun and Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)