The Bearable Loneliness of China’s Solo Karaoke Booths

There’s a listicle making the rounds online in China that describes various activities that exemplify loneliness. People who sing karaoke on their own rank sixth — not quite as solitary as eating hot pot unaccompanied, and certainly not as sad as going to the hospital for surgery alone, which ranks highest.

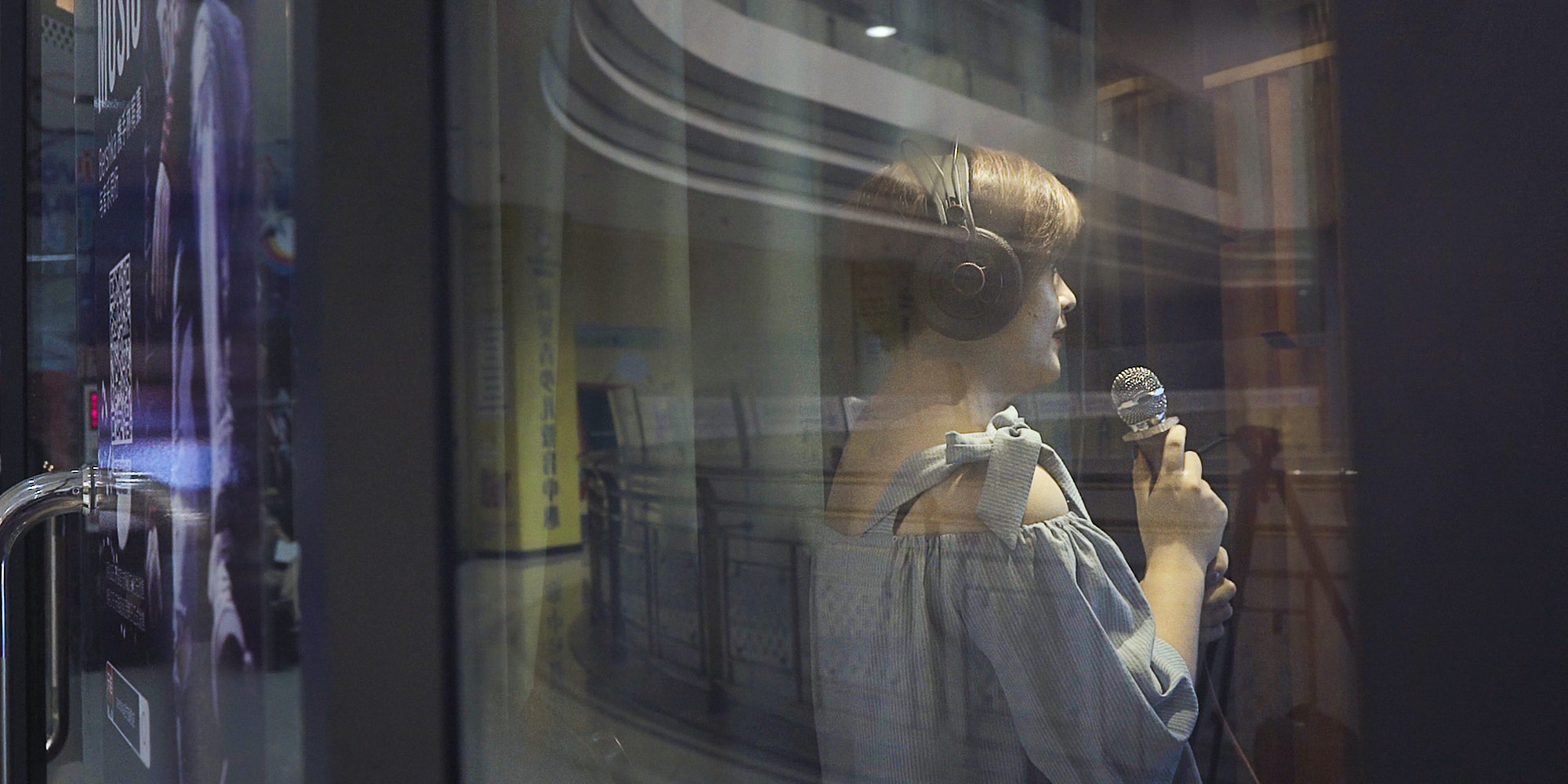

Despite — or perhaps because of — solo karaoke’s social standing, hosts of telephone booth-like KTV chambers have sprung up in cities around China, opening their doors to isolated crooners seeking a way to kill time, while simultaneously escaping their social awkwardness and giving voice to their emotions. These glass boxes also serve to protect the singer from another annoyance in the world of karaoke: judgment from fellow participants.

On a cloudy Wednesday in August, a recently jilted Shanghai native surnamed Ji was looking for ways to keep the post-breakup blues at bay. While waiting in a shopping mall for friends who had invited him to see a movie, the 27-year-old spotted a KTV booth near the cinema and decided to give it a try for the first time.

“I came here to sing, relieve my frustration, and relax,” he told Sixth Tone. But if his intention was to forget his ex, he didn’t seem to be having much luck. Ji selected a cover of a sentimental Mandarin love ballad titled “You Are My Eyes” by Taiwanese singer Yoga Lin.

“My ex-girlfriend loves this singer, and this song as well,” he said, trying to appear nonchalant. Ji paid 20 yuan ($3) for a 15-minute slot in which to sing his heart out, a price he deemed reasonable.

Located in various spots that see heavy foot traffic, such as shopping malls, these KTV booths usually measure around 2 square meters. The tiny glass fortresses of solitude host an array of high-tech equipment: Rooms typically come with a large touch-screen display, two microphones, two sets of headphones, two high stools, and a handful of charging cables for customers’ mobile devices.

Users scan a QR code on the screen inside the booth using messaging app WeChat, which gives them access to the user interface on both the monitor and their smartphones. They can then select from hundreds of thousands of sing-along tracks: a hit rap by a popular idol group; a pounding rock anthem; or a mournful ballad in memory of love lost, like in Ji’s case. Users can record the audio from their performances to savor later or share with friends online.

Currently, there are more than 10 companies offering similar mini KTV services, with packages priced by time and number of songs. According to a report by iiMedia, a research group specializing in internet economy, the domestic market can expect to hit 3.18 billion yuan this year — almost double the figure from 2016.

Solo KTV booths took off last year in China, but a similar concept in Japan has been around since the beginning of the decade. Entrepreneurs in Japan and South Korea have adopted slightly different business models: For example, Japan-based industry pioneer 1Kara operates “ships,” clusters of spaceship-themed KTV booths in a single branch location, instead of separate booths scattered around a city. And while KTV booths from Chinese startups usually carry out transactions via mobile payment apps, foreign brands typically have users pay in cash or through a membership system.

Two Chinese brands — Youchang M-Bar and Mida miniK — lead the domestic market. In February, the former received 60 million yuan in A-round financing, while the latter also secured tens of millions of yuan in strategic investment.

Zhang Qian, an employee at Mida miniK, told Sixth Tone that the company has more than 10,000 booths across the country. “Nowadays, people’s consumption patterns tend to be more personalized, fragmented, and focused on quality,” Zhang said, adding that she believes mini KTV fits this pattern.

Yet it remains to be seen whether KTV booths are just a passing fad, or whether they will gain long-term favor with customers — especially considering the existence of popular KTV apps and traditional KTV establishments. An article from state news agency Xinhua pointed out that the price of mini KTV services is de facto much higher than that of traditional KTV parlors: One hour in a KTV booth can cost up to 80 yuan, while the average price per person at a traditional KTV venue in downtown Shanghai is about the same for stays that typically last around four hours.

There’s also growing official regulation to consider: In July, the Ministry of Culture issued a notice requiring companies to report all KTV booth locations and strengthen guidelines on use by minors.

Cutthroat competition is another challenge for startups in the now-booming industry. In March, Mida miniK sued three other companies for stealing its patented KTV booth design, though the State Intellectual Property Office later approved the competitors’ application for patent invalidation.

What’s more, concerns around hygiene and safety could sour the industry’s future. An investigative piece by Beijing Business Today expressed worries about the reuse of microphones and headsets without sterilization. The lack of frequent maintenance means the small spaces can quickly become untidy or malodorous.

Yet solo KTV booths may be gaining a foothold among a certain slice of Chinese youth. A recent slang term — “empty-nest youth” — describes young people trying to make it on their own in large, crowded cities that offer no sense of belonging. At least 50 million people in China fit this description, according to a report by e-commerce giant Alibaba based on analysis of consumer habits.

Ji Longmei, chief psychologist at the Soulgarden Psychology Consulting Center in Shanghai, attributes the advent of solo KTV in part to the loneliness that often plagues city dwellers. “The urban loneliness epidemic is a social disorder that appeared with the rise of internet technology and lifestyle changes,” she explained.

Whether solo KTV booths have a bright long-term future or are just a short-lived trend, for now, these musical glass boxes offer a cocoon of comfort to China’s loners.

Editor: Colum Murphy.

(Header image: A woman sings in a KTV booth in Shanghai, Aug. 23, 2017. Daniel Holmes/Sixth Tone)